Scope and Findings: China’s Overseas Development Finance Database

By Kevin P. Gallagher & Rebecca Ray

With the release of the new interactive China’s Overseas Development Finance (CODF) Database this past week, a number of analyses and takes have been offered on the data. In this post, we make three clarifying points on the scope and findings of our data:

1. What does it track? – The CODF Database tracks all overseas loan commitments to governments and state-owned entities from China’s two main policy banks operating abroad – the China Development Bank (CDB) and the Export-Import Bank of China (CHEXIM) – to governments, government owned banks and funds, and state-owned enterprises, from 2008 through 2019.

The interactive dataset reveals three key findings:

- Over this time period, CDB and CHEXIM extended $462 billion in sovereign finance commitments: just $5 billion less than the World Bank in the same time frame. This result shows the importance of tracking and analyzing Chinese development finance, which is now by far the world’s largest source of bilateral finance.

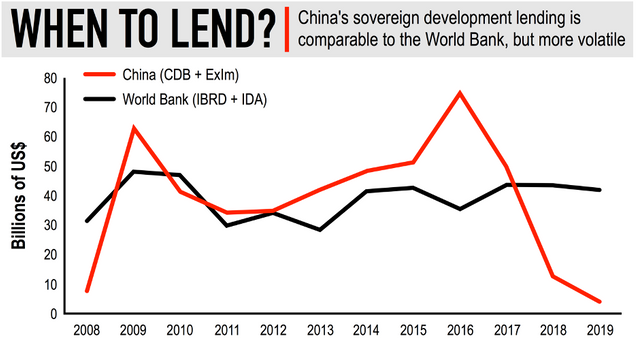

- There has been a significant drop in these types of loans over the past few years. See Figure 1 below.

- The geo-spatial component of this dataset – which is accessible through the online interactive map – shows that significant overlaps exist between this portfolio of loans and three types of sensitive territories: critical habitats, national protected areas and indigenous peoples’ lands.

Figure 1: China’s Development Lending to Overseas Governments, Compared to World Bank, 2008-2019

Source: ‘China’s Overseas Development Finance Database, 2020; World Bank data: https://finances.worldbank.org, latest snapshots, disbursed and un-disbursed.

2. How many and what kind of loans are included? – The CODF Database includes 858 projects: 615 with specific geographic footprints and 243 that do not have footprints.

There are 858 projects in total, and 615 of them are geo-located. The other 243 projects do not have specific footprints that are traceable, as they are in the form of budget support for a country, or on-lending to a borrowing country state-owned enterprise or public bank. The unmapped loans are still included in the total amounts of finance that have been reported, both in our blog post about the database and in media reports.

The CODF Database consists of two parts: the interactive map of the 615 projects, pinpointing their geographic footprints, and a table below the map that includes all 858 mapped and unmapped projects. The ‘About’ and ‘FAQ’ tabs in the top right corner of the interactive offer further guidance on this point.

Source: China’s Overseas Development Finance Database, 2020.

A significant number of Chinese policy banks’ sovereign finance commitments are not tied to specific geographic footprints. For example, Russia is the third-largest borrower in the dataset, having received $37 billion in commitments across eight loans. However, only two of those loans – $97 million for a railway bridge across the Amur River and $6 billion for the Moscow-Kazan high-speed rail – are tied to specific geographic locations and mapped.

The bulk of the financing commitments from the CDB and CHEXIM to Russia are for more general oil operations support. In fact, this type of general support for state-owned oil companies are a crucial part of Chinese overseas finance. It is no surprise that state-owned oil companies are major recipients of Chinese finance commitments in oil producing countries such as Venezuela, Russia, Angola, Brazil and Ecuador.

3. What does it not track? – The CODF Database does not track China’s state-owned commercial bank activity, or services exports through supplier credits.

What is more, as shown in our academic work, the model of Chinese development finance often entails one of these two policy banks creating a general ‘credit space’ that is then filled by Chinese state-owned commercial banks and by services exporters, who can often build and supply equipment to those funded projects. Other databases cover those types of finance, but the CODF Database fills a gap on tracking the ‘first mover’ development finance. Thus, the CODF Database alone should not necessarily be used as the sole barometer of China’s overseas economic activity in general and the Belt and Road Initiative, in particular.

However, the downward trend in overseas lending is supported by our other research. Our recently released ‘China’s Global Power Database’, which includes an estimate of Chinese overseas foreign direct investment in electric power plants, also points to a slowing in commercial finance.

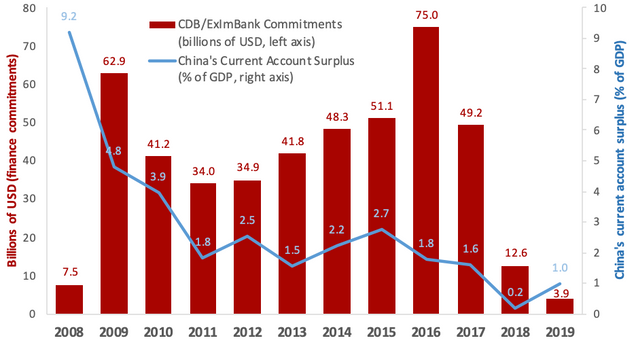

Another trend to note is that China’s overall balance of payments trends also track with our estimates. Figure 2 below shows that China’s current account surplus has been trending downward, similar to the trendline in Figure 1 above:

Figure 2: China’s Overseas Development Finance Commitments and Current Account Balance

Source: China’s Overseas Development Finance Database, IMF World Economic Outlook database.

Our Global China Initiative offers numerous academic papers, working papers, and reports analyzing the trends in China’s overseas economic activity.

Researchers with further questions are welcome to contact us by emailing gdp@bu.edu.