Lost in Translation: Environmental and Social Safeguards for the Laos-China Railway

While investment in infrastructure offers certain benefits, it also poses social, environmental, and human rights risks—such as pollution, displacement, loss of livelihoods, or various modes of insecurity. As more countries turn to China for development and infrastructure finance, the question of how Chinese institutions will improve and ensure social and environmental safeguards has become especially salient.

Environmental and Social Safeguards (ESS) are intended to mitigate negative impacts of investment and development, ensure consultations with project-affected people, and provide guidelines to meet minimum social, environmental, and governance standards. But new data collected between 2018-2020 shows that despite pressure on Chinese policy banks to strengthen regulations for infrastructure construction, the influx of Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) megaprojects in Laos has exacerbated ongoing social and environmental issues, as international and national safeguards are glossed over by priority infrastructure projects.

Attention to Chinese development finance and safeguards have been discussed in terms of sustainability, greening the BRI, local outcomes, and the international order. Reflecting on these themes through the case of Laos-China Railway land compensation and using a multi-scalar approach to development finance safeguards by examining international bank policy, host country law, and local lives impacted by a project, a new working paper asks:

- How do safeguards of international development banks compare?

- Have safeguards improved as existing projects are enrolled in the BRI and with the introduction of BRI finance?

- What host country regulations were in place when project agreements were signed, how have they been updated throughout the project’s development, and how do they translate on the ground?

Additionally, through policy analysis, ethnographic, and qualitative methods, the paper examines regulatory frameworks related to displacement and land compensation for the railway—first, through a comparison of safeguards across Chinese development finance institutions and multilateral development banks; second, how domestic regulations evolved through the project’s development cycle; and finally, in terms of how villagers experience implementation on the ground.

Lenders and Environmental and Social Safeguards

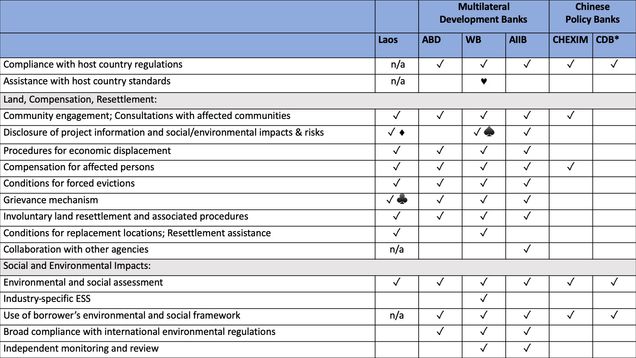

The Export Import Bank of China (CHEXIM), China Development Bank (CDB), World Bank (WB), Asian Development Bank (ADB), and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) are five of the development banks that lend in Laos and also play a significant role across the Global South. Comparing their safeguard policies indicates that Chinese standards have yet to match those of multilateral development banks, see Table 1 below:

Table 1. Comparison of ESS Guidelines on Land, Compensation, Resettlement, and Social and Environmental Impacts

Source: DiCarlo, 2020.

♦Broad information is shared but specifics are not clearly defined or disclosed. are required to host informational meetings on ESIA findings, but the details are typically fuzzy and the ESIA itself is not usually shared.

♥ Not in practice, though this was put in writing in 2018: “The Borrower will establish means of collaboration between the agency or entity responsible for project implementation and any other governmental agencies, subnational jurisdictions or entities that are responsible for any aspects of land acquisition, resettlement planning, or provision of necessary assistance … where the capacity of other responsible agencies is limited, the Borrower will actively support resettlement planning, implementation, and monitoring. If the procedures or standards of other responsible agencies do not meet the relevant requirements of this ESS, the Borrower will prepare supplemental arrangements or provisions for inclusion in the resettlement plan to address identified shortcomings.” (World Bank Guidance Note for Borrowers 2018).

♠ Disclosure “of relevant information”

♣ Projects are typically required to set up grievance committees, which involve both the company and the government. If the grievance cannot be solved through the committee, then the government forces a resolution. How equitable this is or not depends on the agency responsible. There is pressure on communities to avoid “making trouble”, especially in the context of land and priority projects, so grievances are often pre-empted or dealt with informally

AIIB’s efforts to improve infrastructure standards offer a noteworthy comparison, though their actual lending footprint is negligible compared to other banks. While railway financier CHEXIM’s deferential policies point to an “old model” of development finance that is based on deference to host country law.

In addition, the categorization of Chinese finance should be broken down to avoid oversimplifying and homogenizing Chinese projects and standards. Across the increasingly varied development finance landscape, “Chinese” as a blanket classification does not capture the wide-ranging approaches that exist. Rather, Chinese development finance is anything but coherent, as Chinese development finance institutions hedge between traditional development institutions and alternative Southern-led approaches to finance. As there are multiple expressions of development finance, so ESS guidelines range in their specificity, implementation, enforcement, and monitoring.

Domestic Regulations of Laos

Because the Laos-China Railway relies on deferential financing and thus, Lao law, this case also begs the question: which regulations were in place when project agreements were signed and how have they been updated throughout the project’s development over the past decade? Lao regulations—while less comprehensive than the WB, ADB, or AIIB—are more detailed than those of CHEXIM, suggesting that host country deference here could yield relatively positive outcomes.

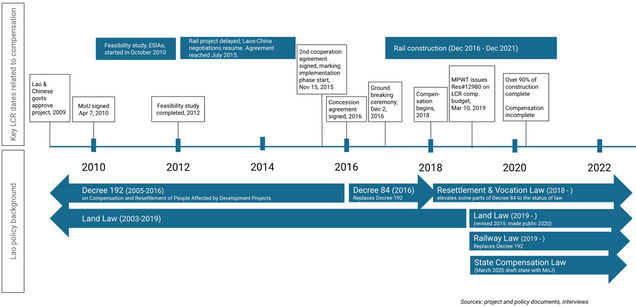

However, as project agreements overlapped and the Lao government issued new laws and regulations throughout the project’s lifecycle, it is unclear which had the final say and should be held accountable:

Figure 1. Key Laos-China Railway Dates and Lao Regulations Related to Land Compensation

Source: DiCarlo, 2020.

Although Lao regulations have been updated during railway construction, they have not necessarily been applied. This may be the case for other projects retroactively enrolled into the BRI, as many projects were proposed under regulations that have since been changed and possibly improved on. In addition, high-profile projects exacerbate ESS challenges, as high-level imperatives and swift construction often trump local concerns. This was the case with the railway Environmental and Social Impact Assessment (ESIA), which passed without review and those working in the responsible ministry were told “it’s a priority project” and the government could not afford it to be delayed by red tape.

Experiences of People in Affected Areas

Finally, through grounded ethnographic fieldwork, an examination of safeguard outcomes on land loss and compensation reveals that although Lao law evolved, implementation was poor and uneven. Many people in affected villages were unclear about plans, timelines, land compensation, and their ability to comment on railway construction. They often explained that if compensation leads to the same or better living conditions (a requirement under Lao law), then they would readily agree, but they have little indication of that happening.

Those more willing to move may have closer government ties, an additional home, family with extra land, or could negotiate better terms. Those less willing to accept compensation tend to lack power to negotiate and clear information, were previously dispossessed of land, or experienced project-induced social or environmental problems.

Villagers’ ambivalence is connected to a number of issues, which while not exhaustive, are primary ways they experience and make sense of the project: delayed compensation, low rates at times, and inconsistent land valuation. These problems exacerbated inequality and led to the displacement of more than 4,000 households, some of whom had been previously displaced. Yet, because the railway is a priority project, many people felt they had no clear means of reprieve or redress, despite safeguards and protections that say otherwise.

This case points to the challenges of continued reliance on host country standards in spite of pressures to improve safeguards domestically and within international development finance. Indeed, deferential financing is often risky for the host country, local communities, and the creditor. It has historically resulted in poor local outcomes and pushback against projects and institutions. Taken together, China’s growing presence in development finance, gaps between written regulations and implementation, and conflicting regulations over long project lifecycles raise questions and offer lessons for bank safeguards.

Key Takeaways

As Chinese institutions reshape the international development finance landscape and the BRI subsumes existing projects, it is critical to dissect how approaches of China’s policy banks compare and interact with host countries’ domestic norms, policies, and safeguards, and how policies operate within and across host-country institutions.

It also underscores the need to examine how policy bank safeguards compare and interact with domestic policies and local implementation. A more fine-grained, project-based analysis of how safeguards are used begins to answer questions of whether the model of deferring to host country’s social and environmental standards used by Chinese development banks translates into sufficient social protection on the ground.

Recent bank activities seem to acknowledge that safeguards are more relevant than ever for China, as relationships with BRI countries will be affected by social and environmental outcomes of investments. For example, in 2019, CDB with the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) published a report, which is one of the first major efforts of either policy bank (CDB or CHEXIM) to publicly address ESS gaps and investment standards. And in November 2020, the AIIB held a consultation meeting to revise their Environmental and Social Framework—a commendable step by a China-led multilateral development bank, which an attendee from China’s Ministry of Finance suggested should be taken as a reference for other Chinese actors in BRI countries. In short, Chinese policy banks must step up ESS systems from the current deferential approach, as CDB’s 2019 step toward “harmonizing” finance safeguards may very well help to do.

At the same time, the Lao government needs to implement and monitor regulations, regardless of the financier or status of a project; otherwise, projects will continue to bull doze the very people they claim to benefit. While there are policy-level frameworks and recognition emerging, outcomes attached to specific projects have yet to be seen.

Jessica DiCarlo is a PhD candidate in the Department of Geography at the University of Colorado Boulder and a former Global China Fellow with the Global China Initiative. She specializes in critical development studies, political ecology, and infrastructure studies.

Read the Working Paper