Joining the Game: China’s Role in Latin America’s Investment Diversification

China’s overseas investments have experienced a significant upward trend since the start of the 21st century, positioning the country as an important source of investments and raising questions about their impact in many countries.

Latin America is no exception. What is the influence of China’s investments in Latin America? More specifically, have Chinese investments been butting into Latin America’s efforts at investment diversification: are they growing at the expense of other investor-countries in the region? Or are these Chinese investments rounding out, thus meeting some of the host country’s demands and interests? In a new working paper published by the Boston University Global Development Policy Center, I set out to investigate these questions.

What is the history of China’s economic involvement in Latin America?

Since the early 2000s, China has been considered both an economic opportunity and a challenge in Latin America, particularly in trade and, most recently, in investments and finance. On the one hand, Latin America has benefitted from “China’s boom”—the period from 2003-2013, as explained by Kevin P. Gallagher in The China Triangle—as some countries in the region gained greater access to one of the world’s fastest growing middle-income markets, as well as more flexible financial opportunities via trade exchanges and financial deals. On the other hand, there remains a lack of diversification in the basket of products traded between Latin America and China, hinting at a potentially unequal exchange, or the premature deindustrialization in countries, like Argentina and Brazil.

While emerging literature examines the impact of China in Latin America, less attention has been paid to the Latin American economies’ approach to interacting with China. In Dragonomics, Carol Wise takes this latter perspective and explores how certain Latin American countries (i.e. Chile, Costa Rica, and Peru) have benefitted more than others in their bilateral exchanges with China. This kind of narrative ascribes more agency to the Latin America region. So to assess the impact of Chinese investments in Latin America, it is useful to also examine the region’s overall investment environment. This would aid the examination of whether the Sino-Latin American relationship has affected ties with other key external actors, and the extent to which China has become a dominant investor.

Thus, it is important to examine the incentives of both investors and host countries. Investors are looking for resources, markets, the increase of their firms’ efficiency and to diversify their portfolios. For host countries, these investments are not only an inflow of capital, they can also enhance innovation and support the recipient’s economic growth and development. Investments are competitive, as host countries create incentives to attract foreign direct investment (FDI). For Latin America, a region with insufficient investment, having a greater number of investment partners is important, as it can expand the supply and diversity of investment options—both in terms of origin (i.e. who is investing) and sectors.

Then, if China is “butting in,” the expectation is that Chinese investments would aggressively displace or “push out” traditional investor-countries, such that China becomes the new dominant player. China would become the main, or only, source of FDI and buyer of assets in Latin America. If China is “rounding out”, then the entry of Chinese FDI would expand the number of investors for Latin American countries, diversifying the region’s investment base. That means China would be joining the game. This would certainly put the region in a more resilient position, as it would distribute Latin America’s investment portfolio among a greater number of investors, rather than in the hands of just a few.

The type of investment also plays a role. Traditionally, investments can be divided in two categories: greenfield FDI, which demands building operations from the ground-up, making this type of investment more costly and riskier for the investor; and mergers and acquisitions (M&A), also known as brownfield investments, which represent a change in ownership (i.e., buying existing assets from a firm). The impact of the former is usually greater in host countries, as it can involve the construction of new facilities, technology transfer, worker-training, etc. Greenfield investments demand a long-term commitment from the investor—but they also need a predictable environment. Political and economic instability can make a host country unattractive as an FDI destination.

What is the current scenario?

An examination of aggregate regional data indicates China has not necessarily replaced dominant traditional partners in the region. Reports by the United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) highlight the rapid growth of Chinese investments in Latin America since 2008, averaging US$10 billion approximately per year from 2010-2014; and yet China remains far from the largest source of FDI in the region.

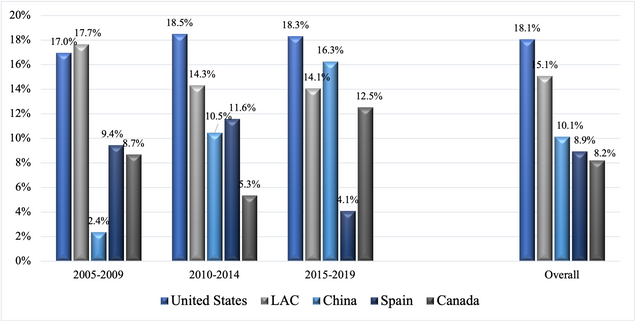

Figure 1: Top Greenfield Investment Flow Sources in Latin America by Time Period, 2005-2019

Traditional partners, such as the United States and Spain, continue to be the largest sources of FDI in Latin America. From 2005 to 2019, both countries were leading investors in Latin America, with total average shares of 22.6 percent and 11.9 percent, respectively.

Intra-regional investments have also been dynamic, shown in Figure 1 as increasing from Period 1 (2005-2010) to Period 2 (2010-2014) in the analysis, but flattening from Period 2 to Period 3 (2015-2019). This is somewhat expected as Brazil, one of the top investors within Latin America, faced the fall of its most important construction and engineering conglomerate, Odebrecht, after the discovery of a series of bribes and fraudulent deals that involved many Latin American governments. While this scandal may have stalled the participation of one major regional player, it also highlighted the growth of other regional investors, like Mexico and Chile.

Table 1: Changes by Time Period of the Top Ten Greenfield Investors in Latin America

Note: Considered an increased if 1 percent or more growth. These are announced investments. The Nicaragua Canal project announced in 2014 was taken out as it never came to fruition.

By sectors and as shown in Figure 2 below, manufacturing has remained the main target of FDI in Latin America, with 24 percent of the overall share in the last 20 years. Communications and IT services rank second, with a 13.3 percent share. Alternative and renewable energy follow in third, with a remarkable growth from 6.6. percent share in Period 1 to 16.6 percent in Period 3. This signals the shifts Latin America is experiencing as it gradually prioritizes industries that focus on environmental protection and sustainability.

In all these instances, China is not a leading investor. Although the country ranks among the top three in mining, transportation and engineering, these industries have received less than ten percent of total FDI flows in Latin America from 2005-2019.

Figure 2: Top Three Sectors China Greenfield Invests in (Latin America), 2005-2019

Note: The Nicaragua Canal project announced in 2014 was taken out as it never came to fruition.

China has rapidly grown as a buyer of Latin American corporate assets as well, growing from a participation share of 2.4 percent in Period 1 to 16.3 percent in Period 3 (see Figure 3 and Table 2) in M&As.

Yet, the interpretation of this growth as an aggressive or predatory move from China should be taken with caution. External conditions and regional circumstances have also played a role in the increase of China’s participation in M&As in the region. The effects of the financial crisis of 2008 and 2009—which were felt more deeply among North Atlantic developed economies—and the Odebrecht crisis in Brazil, made China a very attractive option for many Latin American economies, providing China (and other partners) with the opportunity to buy assets cheaply.

Figure 3: Top Five Buyers in Latin America (M&A) by Time Period, 2005-2009

Table 2: Participation Share of the Top Five Buyers in Latin America (M&A) by period, 2005-2009

Like greenfield FDI, in this instance, the United States is the top buyer of assets in the region with a total M&A share of 18.1 percent, showing no significant changes in Periods 2 and 3. Latin America ranks second, with a total percentage share of 15.1 percent. Moreover, intra-regional transactions did not experience much movement over the last decade, mirroring the United States. China accounts for 10.1 percent of the region’s M&As from 2005 to 2019, holding the third position. China experienced its largest average growth from Period 1 to Period 2, when its participation jumped from an average 2.4 percent to 10.5 percent, as seen in Figure 3.

Yet China’s increased participation does not seem to have displaced Latin America’s top actors. Since 2010, M&A inflows appears to be more widely distributed among the main investors. Between 2005 and 2009, the United States and Latin America together held close to 35 percent of the region’s M&As inflows, whereas the rest of the investing countries had less than ten percent share each. During Period 2 (2010-2014), about 55 percent of M&A inflows was distributed among four sets of players: United States (18.5 percent), Latin America (14.3 percent), Spain (11.6 percent) and China (10.5 percent). In Period 3, the United States, Latin America, China and Canada accounted for more than 60 percent of mergers and acquisitions.

What do these trends mean?

This preliminary analysis of aggregated data shows China has become an emerging investment partner for Latin America, but it does not appear to be an immediate threat to traditional investors in the region.

China is buying as top traditional partners in the region are also selling, and it appears to be filling in some spaces. Furthermore, it is worth noting that China has mostly focused on a select group of countries (i.e. Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Peru), as well as sectors (mining, oil and refinery, energy) in both trade and investments, showing the impact of China in Latin America has not been the same throughout the region and for all industries.

This trend also means responses from the target-countries and the affected sectors vary, depending on the type of investment and other domestic economic policies. As such, the examination of China’s role in Latin America’s investment diversification is very relevant for many Latin American countries.

But the plans and strategies Latin American countries have developed or continue to develop to face China’s economic rise can be just as important, too.

Read the Working Paper