Gaps in Knowledge of HIV Treatment-as-Prevention Hinder Disease Control

By Emanne Khan

Antiretroviral therapy (ART) not only extends the lives of people with HIV. It also prevents sexual transmission of the virus. However, knowledge of ART’s impact on transmission has been slow to gain mainstream understanding and traction.

In 2011, the HIV Prevention Trials Network (HPTN)-052 study received results from a trial of 1,763 couples in which one partner was HIV-positive and one was HIV-negative. The HIV-positive partners were randomly assigned to either start ART immediately or to wait to start ART until their bodies’ immune systems were declining. At the end of the study, there had been 28 transmitted infections in couples who had waited to start ART, but just one case of transmission in the group that had started ART immediately (this breakthrough case occurred in an individual who was not yet virally suppressed).

The trial results demonstrated unequivocally that HIV treatment is a highly effective transmission prevention strategy. Science Magazine dubbed the discovery its “Breakthrough of the Year,” and the study results helped popularize treatment-as-prevention (TasP) as a tool for epidemic control.

Global disparities in knowledge and awareness

Despite the importance of treatment-as-prevention to current HIV policy, Human Capital Initiative Core Faculty Member Jacob Bor and 13 coauthors write in a new AIDS and Behavior journal article that “information on TasP has been slower to disseminate to people with HIV and people at risk for HIV who might benefit from understanding the prevention benefits of ART.”

Bor and coauthors conducted a systematic review of the scientific literature to gain a better understanding of the state of TasP knowledge and attitudes worldwide. The review assessed knowledge and attitudes in all regions of the world; among patients, providers and HIV-positive and HIV-negative community members, tracking changes over time. Bor and coauthors also reviewed studies evaluating the impact of interventions disseminating information on TasP.

Based on their review of 72 relevant studies, Bor and coauthors identified three key findings. First, there remain large gaps in knowledge and awareness of TasP, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa. Second, acceptability of TasP as a prevention strategy generally increases as people learn more about it. Third, interventions that have disseminated information about TasP have had “beneficial impacts” on HIV testing, treatment adherence, viral suppression and stigma reduction.

The researchers focused their literature review on studies with data relating to a population’s awareness, knowledge, attitudes, and acceptability of TasP, as well as studies assessing the impact of TasP information-sharing interventions. Their search included all peer-reviewed studies published in English between January 1, 2008 and October 18, 2020. Year(s) of data collection, location of study, study population, sampling strategy, sample size, sample characteristics, study methods and key results were extracted into a database for review.

After screening nearly 900 relevant studies, the authors were left with 72 studies that met all of their criteria for inclusion in the literature review. Of the 72 studies, 39 pertained to TasP awareness, 31 to knowledge, 44 to attitudes, 34 to acceptability and four to the impact of information dissemination. Of these studies, 64 percent collected data from populations in North America, Europe, or Australia and almost all of these focused on populations of men who have sex with men (MSM) and other sexual minorities.

Accepting treatment-as-prevention increases with knowledge of it effectiveness

Outside of sub-Saharan Africa, awareness of TasP is high amongst MSM populations. For example, 94 percent of respondents to a New York City survey conducted during 2016 and 2017 were aware of TasP, as were 69 percent of respondents to a Vancouver survey conducted from 2012 to 2014 and 85 percent of participants in an Australian study during that same period.

However, the literature also indicates that knowledge of TasP’s proven effectiveness at preventing transmission lags behind awareness of TasP. The authors write that in the previously mentioned New York City survey, “just 39 percent thought [ART] offered ‘a lot’ or ‘complete’ protection against transmission,” despite the same population reporting TasP awareness levels over 90 percent.

In sub-Saharan Africa, where two-thirds of people living with HIV reside, awareness rates are lower. According to the authors, “Interviews in 2015 with South African men with and without HIV revealed that none of the participants was aware of the prevention benefits of ART.” Female sex workers in South Africa also reported low rates of awareness.

Conversely, both awareness and knowledge have increased over time across North American and sub-Saharan African respondents. Bor and coauthors also cite an online survey conducted throughout 2017 and 2018 with over 100,000 sexual minority men in the US. During that period, the group’s knowledge of TasP’s effectiveness increased by one to two percent each month. Additionally, one 2020 study found that 78 percent of men being tested for HIV in an urban South African community knew that people living with HIV who are virally suppressed on ART cannot transmit HIV. However, the existing evidence on TasP knowledge and awareness in different contexts in sub-Saharan Africa is extremely limited.

A second key finding of the literature review pertains to the relationship between knowledge and acceptability of TasP as a prevention method. TasP has been clinically proven to effectively eliminate the risk of HIV transmission, but some populations remain skeptical due to lack of knowledge. For example, in one 2012 study focused on a group of Australian HIV-negative gay men, 92 percent of participants expressed skepticism that ART completely eliminates transmission risk, and only ten percent reported they would rely on TasP alone to prevent HIV.

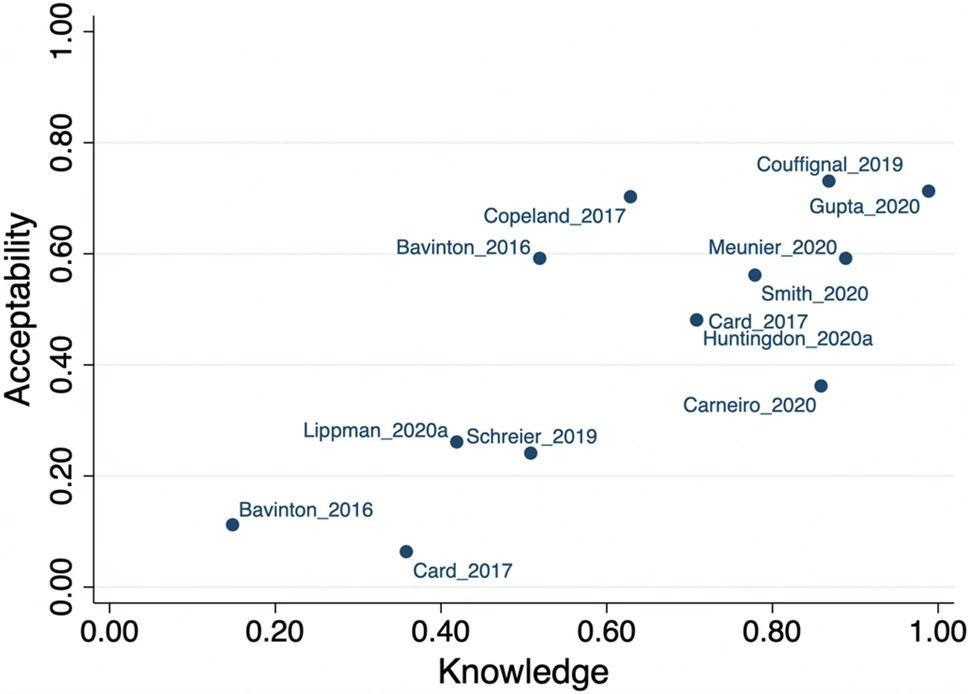

However, Bor and coauthors uncovered a notable trend: higher knowledge of TasP was generally associated with higher acceptability. Figure 1 plots the correlation between knowledge and acceptability as seen in multiple studies. The positive association suggests that a major barrier to uptake of TasP is lack of knowledge of TasP’s effectiveness.

Figure 1: Acceptability of Treatment-as-Prevention Increases with Knowledge

Greater information dissemination would lead to clinical and public health benefits

A small but growing evidence base indicates sharing information on TasP has clinical and public health benefits. In their review, Bor and colleagues identified just four studies that assessed the impact of TasP information dissemination efforts on behaviors and clinical outcomes. Of these four studies, two were based in the US, one in South Africa and one in Malawi.

The two US studies evaluated behavioral interventions in clinical populations of people living with HIV in Atlanta. The first intervention consisted of two one-on-one counseling sessions and five two-hour group sessions on topics including HIV transmission and TasP. Participants who received the counseling sessions on TasP demonstrated “significantly higher adherence” to ART medication than their peers who received counseling on non-HIV related topics.

In a follow-up study, the same research team adapted the previous intensive intervention into a hybrid in-person and remote intervention, consisting of one in-person group workshop and four phone-based sessions addressing TasP and related topics. Once again, recipients of the information intervention reported higher rates of medication adherence. Recipients also reported lower 12-month viral loads, a sign of successful ART-induced viral suppression.

Bor and coauthors emphasize that information interventions don’t need to be as time- or labor-intensive as the two US studies discussed above, in order to induce behavioral change. The South Africa-based study involved clinic outreach workers recruiting men for HIV testing using a flyer and script that emphasized TasP. Although this study was shut down in its early stages due to the COVID-19 pandemic, men who listened to the TasP script and received the flyer agreed to be tested for HIV at higher levels than men who did not.

The Malawi-based study took a different approach, focusing on sharing information on TasP at the community level rather than the individual level. The information intervention consisted of a community meeting, which was conducted in 122 villages. At the meetings, educators used interactive techniques to teach about the health and transmission prevention benefits of ART. In the control villages, meetings only provided information about the health benefits of ART and did not discuss TasP.

The results were striking. As summarized by Bor and colleagues: “In a household survey (n = 1,358) across study villages, 80 percent of people living in treatment villages versus 19 percent of people in control villages mentioned ART as a prevention strategy.” Additionally, treatment villages reported a 36 percent higher HIV testing rate.

The takeaway? The more people know about TasP, the more they accept its efficacy and are open to its use. And as the four studies discussed above suggest, there are numerous benefits to widespread acceptance of TasP, including higher rates of testing, medication adherence and viral suppression. Information interventions aimed at increasing knowledge and awareness are one way of helping communities realize these benefits.

“The potential to improve the quality of life for millions”

The past several decades have seen multiple breakthroughs in the medical community’s response to HIV/AIDS, the discovery of TasP among the most significant. However, as Bor and coauthors note in their discussion, “A decade after the HPTN-052 trial showed that HIV treatment is among the most effective HIV prevention strategies, information on TasP has yet to reach many HIV-endemic populations.”

Bor and coauthors’ findings emphasize the need for influential scientific discoveries to be accompanied by comprehensive information-sharing strategies. Reflecting on the study, Bor writes: “Our review shows major gaps in scientific dissemination and missed opportunities to improve the wellbeing of people living with HIV. It’s time to set the information free.”

Bor and Dr. Dorina Onoya, the senior author of the literature review, are currently leading a project to help remedy this gap. The project, supported by an R34 grant from the US National Institutes of Health, is called “Integrating U=U into HIV counseling in South Africa (INTUIT-SA).” The research team will develop, pilot and evaluate an intervention to assist counselors in discussing U=U with their patients.

Simply put, TasP has the potential to improve the quality of life for millions of people worldwide. However, a decade after the landmark HPTN trial, not all individuals who stand to benefit from TasP are fully informed about it. The review by Bor and coauthors provides persuasive evidence that information-sharing campaigns are needed to ensure all people have access to modern HIV prevention strategies.

Read the Journal Article