Chart of the Week: The Debt-Climate Nexus in Sub-Saharan Africa

By Samantha Igo

As the Group of Twenty (G20) meet in Rome from October 30-31, the triple crisis of climate, COVID-19 and ballooning sovereign debt demands bold intervention.

Countries are reeling from the economic and social costs following a summer of extreme weather events, with only 2.9 percent of people in low-income countries having received at least one vaccine dose. Add to this the looming debt crisis in the Global South, which has been exacerbated by divergent economic recoveries and insufficient global debt relief efforts.

With the G20’s Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI) expiring in December and no plans for a replacement, the G20 should put forward a plan that would reduce debt distress while helping countries recover from the pandemic and pursue resilient growth paths.

As such, a recent report from the Boston University Global Development Policy Center, the Heinrich Böll Foundation and the Centre for Sustainable Finance at SOAS, University of London proposes an ambitious blueprint for comprehensive debt relief to free up resources to invest in nationally determined green policies. The proposal is anchored by a Guarantee Facility at the World Bank to encourage participation from the private sector that has, until now, been missing in debt relief restructuring.

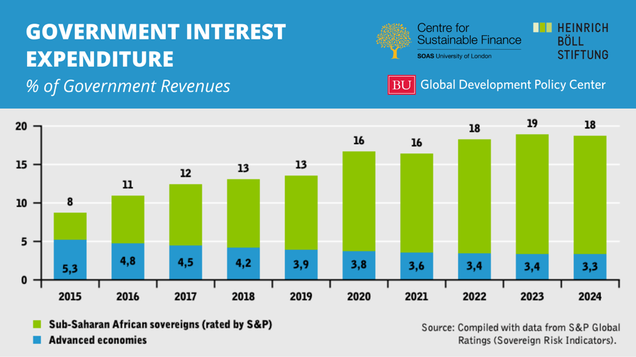

Figure 5 from the report highlights the critical need for a new debt relief arrangement from the G20. The chart visualizes the astounding – and growing – interest burden in 18 Sub-Saharan African (SSA) countries as a percentage of government revenue:

The SSA interest burden has more than doubled since 2015, while for advanced economies, it has dropped by more than a third, according to data from S&P Global. Ghana, Zambia, Angola, Nigeria and Kenya all spend more than a quarter of government resources on interest payments alone. In other words, debt service is severely obstructing decisive pandemic responses, worsening development prospects and commanding more attention than critical social investments, like health, education and climate resilience.

In its latest Regional Economic Outlook for Sub-Saharan Africa, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) projected the region will grow by 3.7 percent in 2021 and 3.8 percent in 2022, while advanced economies are projected to grow by more than 5 percent. SSA is also poised to feel the brunt of the impacts of climate change, from extreme drought and floods to increasing exposure to extreme heat. This is despite the fact that Africa has contributed only 3.8 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions, compared to nearly four times the amount from advanced economies. Economic growth for SSA will be contingent upon global coordination, comprehensive debt relief and adopting – and fully investing in – transformative green transition pathways.

Critically, this debt-climate nexus is not limited to SSA. The United Nations Development Program (UNDP) estimates that nearly $600 billion of external public debt service payments are at risk due to economic stress caused by the pandemic, and just over half of that is owed to private creditors. In 2021 alone, $1.1 trillion is due in debt service payments. Concomitantly, climate vulnerable countries continue to lack access to climate financing as the world experiences a record number of weather disasters with a billion-dollar price tag.

Debt, climate and public health are inextricably linked, and the G20 has an opportunity to provide comprehensive debt relief to emerging market and developing countries. Such a mechanism could stall the growing crisis, alleviate financial pressures and support investment in much-needed climate resilience and adaptation. To do so, the report suggests three key steps: (1) enhancing debt sustainability analyses from the IMF and the World Bank, (2) creating a Guarantee Facility managed by the World Bank to entice commercial sector engagement and (3) devising and supporting green strategies led by country priorities.

As debt distressed countries face the expiration of the DSSI, the G20 must put forward a new climate-aligned debt relief mechanism if the international community is to ward off a full-blown debt crisis in 2022 and suitably prepare for the worsening consequences of climate change. In the meantime, these crises will only grow more expensive.

Read the Report