Webinar Summary – Globalizing Patient Capital: The Political Economy of Chinese Finance in the Americas

On Thursday, February 17, 2022 the Boston University Global Development Policy (GDP) Center hosted Dr. Stephen B. Kaplan, Associate Professor of Political Science and International Affairs at the George Washington University, to discuss his new book Globalizing Patient Capital: The Political Economy of Chinese Finance in the Americas. The webinar was part of the Spring 2022 Global Economic Governance Book Talk Series.

In his book, Kaplan argues China’s overseas financing is a distinct form of patient capital that marshals the country’s vast domestic resources to create commercial opportunities internationally. Its long-term risk tolerance and lack of policy conditionality has allowed developing economies to sidestep the fiscal austerity tendencies of Western markets and multilaterals. Employing statistical tests and extensive field research across China and Latin America, he finds China’s patient capital endows national governments with more room to maneuver in formulating domestic policies. Kaplan also evaluates the potential costs of Chinese financing, raising the question of how Chinese lenders will react to developing nations’ ongoing struggles with debt and dependency. In all, his book spells out the significant implications of the rise of China in Latin America, offering new insights about globalization and showing the costs and benefits of state versus market approaches to development.

The result of 20 years of research on Latin American engagement with China in the areas of finance, trade and investment, Kaplan was motivated to address questions like, what are the implications of China’s increasing global finance? In what ways does it differ from Western multilateral and private financing? And what economic and political consequences do these unique characteristics have for borrowing countries?

During the talk, Kaplan argued China’s global finance and investment provide borrowing countries with more policy autonomy and room to maneuver in the face of capital exits from Western and private capital. Chinese capital provides this space because it is risk tolerant and more likely to weather economic booms and busts compared to Western and private capital, and because Chinese lenders does not impose policy conditions on borrowers, relying instead on commercial conditions to ensure repayment. This increased fiscal space has provided important benefits to Latin American states, including long-term financing that aligns with development goals and infrastructure to meet the region’s growing needs. However, Kaplan warned that it comes with costs, such as commercial conditionality, rising indebtedness, reinforced commodity dependency and growing fiscal deficits.

According to Kaplan, China’s global finance is unique in three primary ways: its long-term maturity structure, high risk tolerance and lack of policy conditionality. First, China’s loans have an average maturity of 17 years, compared to five years for private creditors. This long-term horizon stems from the goals of this financing, which aims to catalyze finance and investment in strategic credit spaces. Led by official financing, China seeks to gain access to cheap assets, secure market shares for its companies and improve key logistical skills in its firms. These loans provide Chinese companies an entry point into a new strategic credit space, as they did in Brazil. Additionally, a significant proportion of these loans support infrastructure projects in Latin America, which has one of the largest infrastructure gaps in the world. The nature of large energy, transportation and telecommunication infrastructure projects requires longer commitments, which short-term, profit driven capital typically available to Latin American countries cannot offer.

Second, China’s global finance has a much higher tolerance for risk, especially when entering new markets, than Western multilateral or private creditors. Kaplan found China’s overseas finance and investments are more likely to be active in both boom-and-bust times for its borrowers. For example, after the 2008 global financial crisis, Brazil’s economic crisis in 2014 and the Lava Jato bribery scandal in 2015, Chinese foreign direct investment (FDI) in Brazil spiked, even while Western investors were pulling their capital out. This again builds on China’s priority of opening strategic sectors to Chinese economic activity; China can secure assets cheaply when Western investors sell out from high-risk assets following financial crises. China tolerates this risk, knowing that over the long term, benefits will accrue to Chinese policy banks and enterprises.

Figure 1: Chinese Investors Buy Cheap Brazilian Assets (US$ billions)

Third, China’s global finance is unique in its lack of policy conditionality. However, Kaplan emphasized this does not mean Chinese loans come without any conditions. Instead, Chinese financing often carries commercial conditionality, which ranges from traditional tied aid to commodity-backed loans. This approach is rooted in China’s official doctrine of non-intervention, outlined in its Five Principles for Peaceful Coexistence, and in developing countries’ emphasis on sovereignty in international affairs. These commercial conditions support China’s larger goals of market maximization by requiring high ratios of Chinese content, guaranteed contracts for Chinese companies and commitments to buy Chinese machinery or equipment. As Kaplan noted, these conditions are not always presented transparently, citing the example of limited information on environmental impacts of the hydroelectric facilities in Santa Cruz, Argentina. In addition to promoting Chinese commerce, this type of conditionality also helps China manage sovereign risk through collateralizing commodities, such as oil or other resources, invoking cross-default clauses and requiring state-backed commercial insurance. In summary, China’s global financing differs from Western and private creditors in its long-term horizons, high risk tolerance and use of commercial conditionality.

To understand the political and economic consequences for Latin American countries, Kaplan highlighted the distinction between the state-to-state and market channels for finance. He presented two case studies from Argentina to illustrate these differences, as well as the larger implications of China’s financing. Argentina provided a state guarantee for the concessional loan used to finance construction of the Santa Cruz Hydropower Stations. While approximately one-fourth of the loan paid for Chinese machinery and equipment, such as turbines, the other three-fourths had more flexibility and could be directed towards fungible civil works projects. This contract also contained a cross-default clause, wherein cancellation of the hydroelectric facility project would result in cancellation of the Belgrano Cargas Railway project, which Argentina viewed as central to its development goals. The project faced delays when an Argentine Supreme Court ruling put a stay on the project until its environmental consequences could be investigated more fully and transparently, resulting in a reduced number of turbines and generating capacity. According to Kaplan, this state-to-state financing can be characterized by increased discretion for borrowing countries, higher indebtedness and reduced transparency.

In a contrasting case of market-oriented finance, Argentina contracted Shanghai Electric Power Construction through a private procurement system, RenovAr, to build the Caucharí solar parks in Jujuy Province. While the project was ultimately supported by a $331 million loan from the Export-Import Bank of China, the financing went directly to a corporate enterprise rather than the Argentine state. The financing came with requirements to buy Chinese machinery and equipment, but lacked the discretionary element present in the Santa Cruz financing. Due to the private auction process, however, Argentina’s laws required the consent of local communities to move forward with the project, leading to greater transparency and benefits for the community, including profit participation and training for jobs in the construction and operation of the plant.

Kaplan’s juxtaposition of the two Argentine cases demonstrated the need to approach analysis of Chinese financing based on its intended recipients, states or corporations, with the state-to-state channel in particular having far-reaching impacts on Latin American countries.

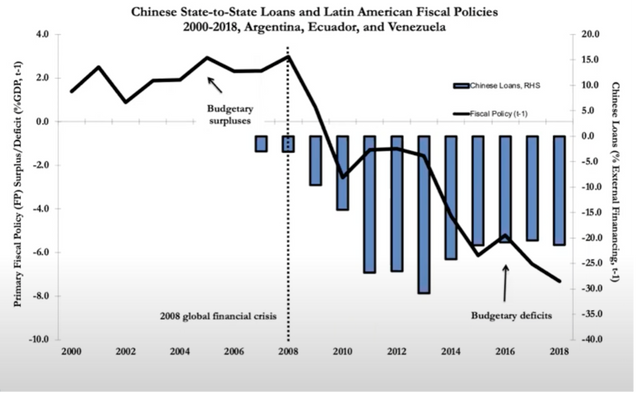

Next, Kaplan presented extensive empirical analyses demonstrating the larger political and economic implications of China’s global financing, emphasizing the state-to-state channel as the mechanism for these consequences. He demonstrated that as bilateral financing from China accounts for a greater share of total external financing, government budget deficits increase. Compared to Western multilateral financing and private credit, which are more likely to lead to positive primary budget balances (fiscal balances not including debt interest payments), China’s financing leads to primary budget deficits, indicating enhanced fiscal space for borrowers. Citing the experiences of Argentina, Ecuador and Venezuela surrounding the 2008 global financial crisis, Kaplan noted that prior to 2008, these three countries had budget surpluses, even under left-leaning governments. After 2010 though, with the arrival of Chinese finance, all three countries entered sustained budget deficits. To Kaplan, the pre-2008 reliance on Western and private creditors constrained the fiscal space of these governments and enforced budget surpluses, even when leaders would have preferred higher spending to counteract the economic crisis. Only Chinese finance provided the space to do so.

Figure 2: Patient Capital Enhances Policy Flexibility

Kaplan concluded by discussing the outlook for China’s financing in Latin America. China has begun to pursue a more diversified finance and investment strategy, channeling less finance through bilateral official loans in the wake of the 2014 commodity downturn and resulting debt distress among Latin American countries. One new funding mechanism has been state-backed private equity funds, which allow China to invest in equity instead of debt and to focus on procurement. Another mechanism has been increased multilateralism; Kaplan highlighted the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank’s (AIIB) cooperation with the World Bank, increased lending from China’s commercial banks and partnerships with other local development banks.

While the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic in China, Latin America and across the globe remain uncertain, Kaplan argued alternative financing mechanisms may grow in importance, both to protect Chinese investors and to reduce debt burdens for Latin American countries.

*

Never miss an update: Subscribe to updates from our Global Economic Governance Initiative.