5 Design Features for a Transformational Resilience and Sustainability Trust at the IMF

By Samantha Igo

Amid the social and economic stress of the COVID-19 pandemic, emerging market and developing countries have faced severe liquidity bottlenecks while working to implement responsive public health and economic policies. Compounded by an already-looming debt crisis, the economic distress led experts and civil society organizations to advocate for the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to make a substantial issuance of Special Drawing Rights (SDRs) – the IMF’s reserve asset – to help ease growing tensions. Then, in August 2021, IMF Managing Director Kristalina Georgieva announced a historic allocation of SDRs worth $650 billion.

Following the allocation, the IMF announced it was considering a ‘Resilience and Sustainability Trust’ (RST) to help facilitate re-channeling of SDRs, because the IMF’s quota system meant the majority of these resources flowed to more advanced economies, even though they aren’t facing the same economic pressures as emerging market and developing countries. In October 2021, the Group of 20 (G20) also called on the IMF to establish such a Trust, with a very clear mandate of providing climate vulnerable nations with access to short-term and long-term financing in face of the climate crisis. While an RST has enormous potential to fill a gap in the international financing architecture, the design particulars of the RST, as of now, render it unattractive to much of the IMF membership, essentially locking up billions of dollars in climate- and pandemic-fighting resources.

A new policy brief from the Task Force on Climate, Development and the IMF underscores five design features critical to ensuring the RST has transformational impact for developing countries. The features include broad eligibility criteria; concessional terms, short- and long-term financing and access that is not conditional upon having an existing IMF program; a focus on country ownership; collaborative governance with the World Bank and other multilateral development banks (MDBs); and scale commensurate with the needs of vulnerable countries facing the climate crisis.

1. Broaden eligibility and scope

The latest design from the IMF states eligible countries will include countries with per capita gross national income (GNI) below 10 times the 2020 International Development Association (IDA) operational cutoff, or about $12,000. However, as climate vulnerability is a multidimensional concept, income-based metrics alone should not be used to determine eligibility to the RST.

Climate impacts may amount to a major share of gross domestic product (GDP) of climate vulnerable nations. For example, Dominica—classified by the IMF as an upper middle-income country—suffered damages amounting to 90 percent of its GDP due to Tropical Storm Erika in 2015. Just two years later, in 2017, Hurricane Maria resulted in damages amounting to 226 percent of Dominica’s GDP. In other words, even though countries may have higher per capita incomes, the sheer scale of climate impacts means they will need access to instruments like the RST, too.

2. Provide concessional terms with no requirement of existing IMF programs

If the rates charged by the IMF are too high and the access terms are too restrictive, countries will be deterred from using the RST. Accessibility has two elements: rates and terms, and linkages with existing IMF programs.

As for terms, there is precedent in the IMF’s Poverty Reduction and Growth Trust (PRGT) to offer concessional terms with zero interest. Unlike the PRGT, however, the maturity periods for RST resources should have a lifespan of more than 20 years. The longer maturity is warranted for three reasons: (1) risk financing and long-term adaptation needs, (2) the transition away from fossil fuels will require sustained efforts and (3) climate impacts are not simply one-off extreme weather events but cumulative in nature, including slow onset impacts.

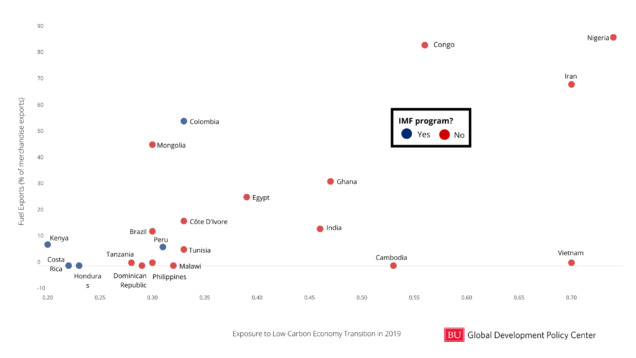

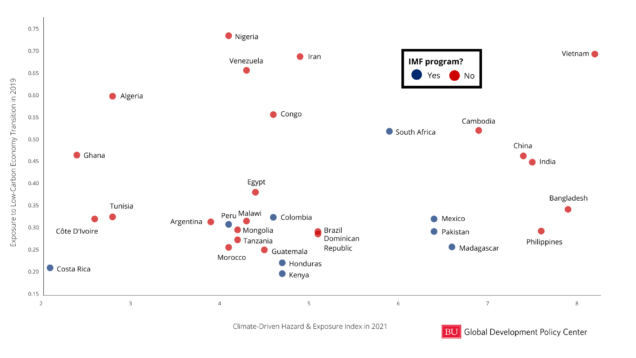

As for linkages with existing programs, many climate vulnerable countries do not have existing IMF programs. This will exclude these countries from accessing vital resources, regardless of the IMF using metrics beyond income for eligibility. Figures 1 and 2 below demonstrate the extent to which vulnerable countries would not be able to capitalize on the RST.

Figure 1: Do Countries Facing High Transition Risks have IMF Programs?

Figure 2: Do Climate-Exposed Countries have IMF Programs?

When RST resources are coupled with existing financing programs, two considerations need attention. First, existing IMF programs were not designed with the goal of helping countries tackle climate change. Adding RST resources to programs that have fundamentally different objectives, regardless of their merit, will reduce the ability of the RST to help countries address the climate crisis in a meaningful way. Second, if the RST resources are simply used as a ‘sweetener’ to make the terms more appealing to member states with existing IMF programs, the RST may lose its potential for transformational impact. There will be no guaranteeing that these extra resources will have contributed any additional impact on existing climate efforts.

3. Prioritize country ownership and avoid conditionalities

Country ownership needs to be the organizing principle for RST support. Nationally determined contributions (NDCs) have already been submitted under the Paris Agreement, and they are the clearest articulations of how countries intend to tackle climate change. However, a critical unanswered element is identifying how to mobilize the investment required for each country to achieve its climate objectives. As such, NDCs should form the basis of RST support. The IMF needs to actively work with countries to implement programs that facilitate the mobilization of resources, while also playing a leadership role in global policy coordination and capacity building in preparing for climate shocks.

The IMF’s own research and other scholarly literature have shown how ineffective IMF conditionalities can be in achieving their intended social or economic outcomes, and in fact, they often deter borrowing countries from approaching the IMF at all. Furthermore, these conditionalities usually include fiscal consolidation, and such requirements would run directly counter to investing in low-carbon growth.

4. Ensure collaborative governance

Along with the IMF, MDBs also need to be engaged in the RST’s governance. MDBs, including regional development banks, will allow countries to leverage greater resources and tap into MDB and regional development bank expertise in climate programming. At a fundamental level, countries will need a mix of financing instruments to mobilize finance at the necessary scale. Therefore, IMF financing via the RST will have to be viewed considering other financing available through MDBs as well.

5. Build to scale with self-replenishment mechanisms

The scale of resource mobilization needed to support low-carbon, climate resilient pathways for developing countries is immense. The estimates of demand for the RST’s resources need to be informed by these financing needs. The V20 has called for the RST to be capitalized, at minimum, at $100 billion, and at the 2021 United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP26), Barbados Prime Minister Mia Mottley called for an annual allocation of $500 billion in SDRs for the next 20 years to finance sustainability and resilience. The RST will need built-in triggers to replenish its resources and ensure sustainability of its funding stream.

*

The difference in impact of a poorly- or well-designed RST will be significant. The IMF can either develop a responsive, sustainable tool countries can make use of to pursue their climate and development aspirations, or the Trust could be designed with serious accessibility issues that may actually undermine the climate goals the IMF seeks to promote.

At the Paris Peace Forum in November 2021, IMF Managing Director Kristalina Georgieva said the design of the RST would be ready for IMF Board approval by the 2022 IMF and World Bank Spring Meetings, with the goal of making the RST operational by the Annual Meetings in the fall. There is still time to improve the design of the RST, and these five design features outline a path for the Fund to lead on resilience and sustainability for decades to come.

Read the Policy BriefNever miss an update: Subscribe to updates from the Task Force on Climate, Development and the IMF