The IMF’s Resilience and Sustainability Trust: A Ray of Hope or Financial Black Hole for Climate Vulnerable Economies?

By Sara Jane Ahmed and Rishikesh Ram Bhandary

The International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) allocation of $650 billion in Special Drawing Rights (SDRs) last August was one of the boldest steps taken by the international community to help countries recover and rebuild from the COVID-19 pandemic.

Now, the Resilience and Sustainability Trust (RST) proposed by the Fund to facilitate re-channeling of SDRs to vulnerable countries stands to fill a critical gap in the international financial architecture, especially for climate action. The IMF has said it aims to release the design for the RST by the Spring Meetings later this month and implement it by Annual Meetings in October.

The establishment of the RST marks a paradigm shift for the IMF as the Fund seriously begins incorporating climate into its work. Last year, the IMF completed its Comprehensive Surveillance Review and committed to integrate climate risk into its surveillance functions, and released its climate strategy, identifying how it plans to integrate climate across its tools and significantly expand its pool of experts.

The IMF has a major opportunity to play a central role in climate action by ensuring the design of the RST is truly fit for purpose. Doing so will require more work over initial proposed designs, building on the IMF’s know-how and experience and the needs of climate vulnerable nations.

The RST should offer concessional terms to protect over-burdened countries from the high cost of capital and its resources should not be locked behind onerous conditionalities. While there may be greater fiscal flexibility over the long-term for emerging markets and developing countries, including the V20, the cost of capital and immediate liquidity needs requires urgent support.

This is especially so taking into account expensive debt, with existing levels ballooning across the Global South in the wake of COVID-19. Advanced economies have also started raising their interest rates, meaning heavily indebted economies will see their debt payments climb even further. In its latest World Development Report, the World Bank sounded the alarm on the potential impacts of delayed action on distressed loans and reduced access to credit. What is more, research has shown climate vulnerable countries are already paying a higher cost of capital than other countries – for every $10 paid in interest by developing countries, an additional dollar will be spent due to climate vulnerability.

It follows, then, that the RST must be low-cost and not exacerbate existing debt burdens. If it offers resources close to the market rate and with the IMF’s business-as-usual conditionality, countries will be deterred from engaging with the RST at all, regardless of how critical the resources are. As Senegal’s Minister of Economy, Planning and International Cooperation, Mr. Amadou Hott said recently, “SDRs should become perpetual allocation to the countries with 0.05 percent interest payment without having to repay the SDRs.”

Focusing on climate vulnerability means the IMF needs to re-think its usual approach to calibrating interest rates with income. Countries deserve concessional rates given their climate exposure, regardless of income status. For example, Dominica, which is classified as an upper middle-income country, suffered damages totaling to 226 percent of its GDP following Hurricane Maria in 2017, and just two years prior, Tropical Storm Erika wiped out 90 percent of its GDP.

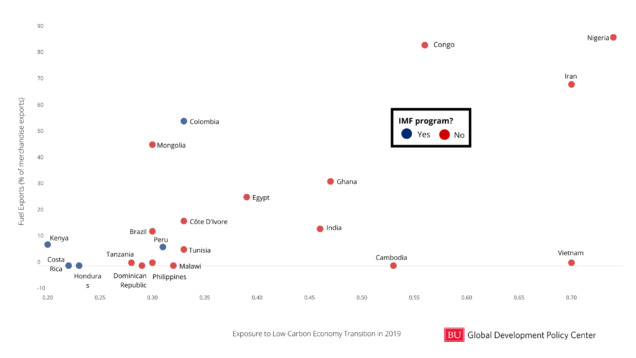

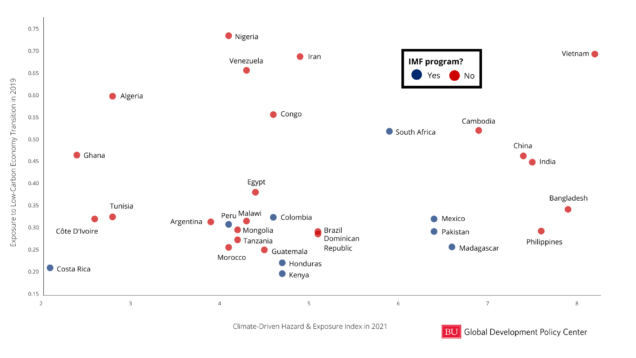

Concessional loans, however, will not be enough. The IMF should help countries increase the urgency and scale of international climate investments. To access the RST, the IMF is requiring countries already be enrolled in an IMF-supported program, posing an issue on two fronts. First, pre-conditioning RST access to an existing IMF program excludes many climate vulnerable countries, as demonstrated in Figures 1 and 2 below.

Figure 1: Do countries facing high transition risks have IMF programs?

Figure 2: Do climate-exposed countries have IMF programs?

Second, IMF programs often require slashing budgets and reducing expenditure. The IMF’s own research has shown fiscal consolidation requirements often do not help countries achieve economic or social objectives, and these measures would be vastly counterproductive to the heavy investment required for combating climate change and building resilient economies. In other words, existing IMF programs could undermine the very objectives of the RST.

The IMF is also requiring countries to have a ‘package of high-quality policy measures.’ While there is very little clarity on what policy measures would qualify, the Fund would do well to consider supporting further policy development where needed rather than conditioning it.

Can the IMF learn from its past and develop an RST that is effective, accessible and lives up to its potential, or will the RST’s own constraints make it unattractive to the countries that need it most? To ensure the latter, the IMF should provide concessional terms with no requirement of existing IMF programs, prioritize country ownership and avoid conditionalities. We likewise urge the IMF to rethink and recalculate debt limits to take climate change into consideration. The progress made so far is welcomed, including recommendations from the Vulnerable 20 Group of Finance Ministers (V20) to remove the cap on the total volume of financing that can be accessed.

The international community must not lose sight of the ambition that led the IMF to this point. The RST has the potential to be an important pilot paving the way for scaled up allocations and regular SDR replenishment. If designed properly, the Trust can show the world how SDR allocations can be used to support climate goals.

*

Read the latest research from the Task Force on Climate, Development and the IMF. Never miss an update by subscribing to the Task Force Newsletter.