Webinar Summary – How China Escaped Shock Therapy: The Market Reform Debate

By Kate Chi

On Thursday, April 21, the Boston University Global Development Policy (GDP) Center hosted the third webinar in the Spring 2022 Global Economic Governance Book Talk Series. The talk featured Isabella Weber, Assistant Professor of Economics at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst and author of How China Escaped Shock Therapy: The Market Reform Debate, and was moderated by William N. Kring, Executive Director of the GDP Center.

In her book, Weber assesses how China has become deeply integrated in the world economy, where gradual marketization has facilitated the country’s rise without a wholesale assimilation to global neoliberalism. In the first post-Mao decade, reformers were sharply divided: should China destroy the core of the socialist system through shock therapy, or should it use the institutions of the planned economy as market creators? With hindsight, the historical record proves the high stakes behind the question: China embarked on an economic expansion commonly described as unprecedented in scope and pace, whereas Russia’s economy collapsed under shock therapy.

Based on extensive research, including interviews with key Chinese and international participants and World Bank officials, as well as insights gleaned from unpublished documents, her book charts the debate that ultimately enabled China to follow a path to gradual reindustrialization.

Weber began her presentation recognizing that, when she began work on this book, she could not have predicted how timely this discussion would be, as the world faces Russia’s war in Ukraine and the lingering economic toll of the COVID-19 pandemic.

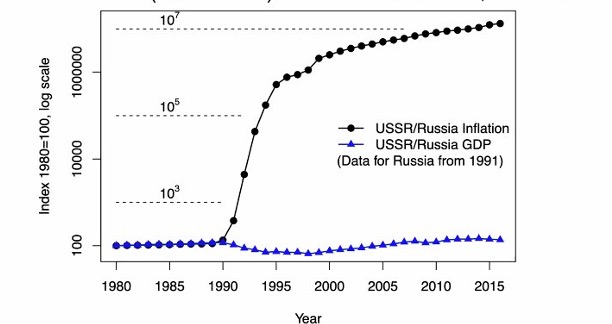

In her work, Weber reveals the stakes of different paths faced by countries at a crossroads in the 1980s. For China, there was economic convergence with the West without wholesale institutional assimilation, despite marketization in the 1980s. This ultimately led to consistent and rapid growth in real gross domestic product (GDP) from 1980 to 2015. For Russia, the 1990s following the dissolution of the Soviet Union saw a severe period of deindustrialization, with a sharp collapse in Russia’s average income per capita. The basic economic policymaking logic in Russia during this period was shock therapy, commonly summarized as a composite of four economic policies, including price liberalization, macroeconomic austerity, trade liberalization and privatization. China, however, took a different economic reform approach.

Figure 1: Russia: Hyperinflation & Collapse – USSR and Russia (from 1990) CPI and Real GDP, 1980-2016

Given this divergence, Weber’s book attempts to address one key question: what are the economics of China’s reform approach? In answering this, she confronts the fiercely debated question within China during the 1980s of how to introduce market mechanisms into China’s command economy.

Debaters agreed market reform was needed; however, there were multiple opinions on how to institute such structural economic reforms. Weber spoke of two main camps of reformers: one comprised of young intellectuals who were self-trained in Marxist classics, Maoism and Western social sciences. This group is identified as dual-track market reformers, who embraced an economic system where central command authorities managed the production outputs to deliver and receive raw materials and intermediate goods. The central command authority would set prices low for these outputs in important sectors (upstream sectors) to encourage more production. Simultaneously, prices in luxury consumer goods and retail (downstream sectors) were intentionally set high to extract liquidity from households and achieve price stability. Within this system, producers began to demand downstream sector goods, which led to an expansion of market demand for final goods. Such a dynamic was coupled with more demand for raw materials and intermediate goods to produce those goods. Ultimately, these forces would lead to an economic system with spontaneous emergence of market mechanisms. The second camp was termed “package” price reformers by Weber, which were largely middle-aged established individuals endowed with orthodox socialist training and modern US economic theories.

In 1985, dual-track approach became national policy in China to install a price management system and expand market demand. Weber highlighted four components of this new policy: letting go of “small” unimportant commodities, reforming the price management system, adjusting important prices in small steps and participation. After having enlivened prices by letting them go, the state had to participate in the market to regulate prices in the first years after the liberation. This included the state having stocks to be able to add supplies to the market when the price was rising too high and purchased when the price was falling too low.

In opposition, package price reformers critiqued the dual-track system. They claimed it created friction and contradiction in the markets, in addition to being inherently vulnerable to corruption. Package price reformers advocated for imposing tight fiscal and monetary policy, where all planned prices are first calculated based on the economy as a whole. Then, central command authorities would let go of core prices in raw materials and intermediate goods, also known as a “Big Bang,” allowing prices to adjust without intervention for goods in the upstream and downstream sectors. This would inevitably replace market participation by the state with indirect macro-control, as well as wage and tax reform. Yet, the “Big Bang” doctrine, with rapid price liberalization at its core, causes cost-push inflation without an adjustment in relative prices and quantities. The center of the debate was whether to maintain central command or to relax price management of inessential consumer goods, specifically highly profitable goods in surplus.

A series of events followed the emergence of the two camps of reformers. In 1986, Premier Zhao Ziyang, proponent of package price reform, established a Program Office for implementation of price liberalization, yet his plan was halted due to intervention by dual-track reformers. In 1988, Deng Xiaoping voiced resistance to carry through price reform that would lead to long-term negative effects on the economy.

Weber characterized the logic of shock therapy as allowing fundamental drastic reforms (“shocks”) to the old economic system to achieve a theoretical economic model. Conversely, the logic of the dual-track system was grounded in an analysis of prevailing economic forces and institutions to identify ways to create reform dynamics at the margins and reindustrialize without undermining social stability. In other words, the dual-track system reformed at the margins to reform the core, whereas shock therapy sought to reform the core and the margins by extension.

To conclude, Weber characterized China’s escape from shock therapy as the adoption of the dual-track system which, shaped the nation’s trajectory and facilitated economic growth. Several other components also contributed to the escape, including the fact that political leaders were unprepared to risk the survival of the Communist state and compromise their vision for long-term economic development. Furthermore, the “Big Bang” demonstrated an inability to create a viable market economy despite seemingly credible scientific solutions. Meanwhile, the dual-track system gradually emerged as a policy alternative through experimental reliance on techniques of market creation by the state, differentiating between essential and inessential consumer goods, and relying on analytical valuation of concrete economic dynamics.

In the Q&A portion of the discussion, Weber emphasized that this method would not have necessarily been applicable across the board; Russia, for example, could not have duplicated China’s approach with the same success. Weber’s book offers historical examination of the crossroads in the 1980s and uncovers contestations of China’s economic reform and its escape from immediate trade and market liberalizations.

Kate Chi is a Research Assistant with the Global China Initiative at the Boston University Global Development Policy Center and a graduate student in the Department of Economics at Boston University.

*

Never miss an update: Subscribe to updates from our Global Economic Governance Initiative.