In Debt Restructuring, is a “Haircut” Better than “Rescheduling?” New Research Shows They are Comparable Approaches

After nearly three years of the COVID-19 pandemic and its aftermath, the global economy is facing three overlapping crises: 1) the climate crisis, as shown by extreme weather disasters, 2) Russia’s war in Ukraine, which has led to energy and food prices to skyrocket and 3) capital outflows from emerging markets and developing countries, which have exacerbated sovereign debt distress in these countries.

There has been much media attention on what creditors will do in the case of Zambia’s debt restructuring. It seems there are two approaches: the Paris Club member countries prefer to have a haircut (debt forgiveness), whereas China seems to have been using rescheduling and re-profiling in recent years (as in the case of Angola and Ecuador). In addition, China announced last month that it would cancel 23 interest-free loans to 17 African countries, which the Boston University Global Development Policy Center estimates could amount to between $45 million and $160 million.

In general, is a “haircut” superior to “debt rescheduling with lower interest rates?” The short answer is no.

First, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) noted in its recent debt sustainability analysis on Zambia that next steps should include, “at least (i) the changes in nominal debt service over the IMF program period; (ii) where applicable, the debt reduction in net present value terms; and (iii) the extension of the duration of the treated claims.”

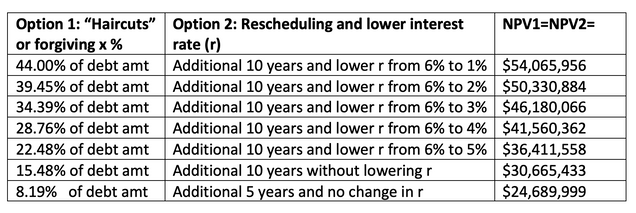

To understand what “net present value (NPV) terms” means, we conducted an exercise using the IMF’s definition of NPV for debt. We calculated the NPV of “forgiving x percent of debt,” and then the NPV of “extending the loan from ten years to 20 years at a lower interest rate of y percent.” In the third step, we equalized the former (aka NPV1) to the latter (aka NPV2), finding the solution for x (percent of forgiveness) and y (percent of interest rate on the loan). For every value of x, there is a y which equalizes the NPV1 and NPV2.

For instance, a forgiveness of 39.4 percent would have the same NPV of an extension of ten additional years at a reduced interest rate from 6 percent to 2 percent. A forgiveness of 28.76 percent would be equivalent to an extension of ten additional years at a reduced interest rate from 6 percent to 4 percent. In this way, the gains for the debtor country should be equal in the two options and creditors can find an “equitable treatment” for their different approaches.

In fact, both “haircuts” and “rescheduling” have been used in meeting specific needs of debtors and creditors for distressed resolution exercises. This has been the case for the Paris Club throughout the years and it was also the case for the Brady Plan in early 1990s. Debt sustainability means helping debtor countries acquire sufficient cushion to serve the debt every year throughout the life of the debt. This can be achieved through haircuts, rescheduling, as well as the natural hedge through structured finance solutions to mitigate the volatility of net cash flow brought by the boom-bust cycles. The natural hedge can be achieved through the use of commodity-price-linked bonds or other forms of state-contingent debt instruments.

In Table 1, we provide the detailed calculation comparing two options of debt restructuring on a $100 million loan with a discount rate of 10 percent, where contract interest initially was 6 percent, finding solutions for x and y by equalizing NPV1 to NPV2. The NPVs in the last column represent the benefits obtained by debtor countries in the future, discounted to the present value.

Table 1: Debt Restructuring: Comparable Options in NPV Terms

Secondly, we find “short term pain” is not always superior to the “long term pain” of debt restructuring. As investors know, in hard infrastructure construction projects, creditors have to jointly bear the operational risks, currency and term mismatch risks, external disaster risks and political risks. Having completed many hard infrastructure projects in host countries, which become part of the host country’s public assets, generating social services such as electricity and road services is critical to the host country’s human welfare, the creditor banks are bearing the cost of external shocks, macroeconomic mismanagement and the consequence of opening capital accounts leading to large capital flights, and local currency depreciation. These banks (and their insurers) are providing international insurance for the political and external risk in the global environment. The host countries are benefiting from this insurance function, that was not correctly “priced in” by the financial market (as in market failures).

It is high time for the international community to recognize the need to provide public assets in low- and middle-income countries and correctly value and “price in” the “insurance” function of patient capital as provided by the multilateral and bilateral development banks and other development partners. Patient capital holders face long-term depreciation, financial and geo-political risks. If the risk premiums are not priced in, there will be fewer entities willing to invest in green and sustainable development, especially in low-income countries.

The premiums required to cover the above-mentioned risks are reflected in the “discount” rate used for the NPV calculation. When equating haircuts and rescheduling for our simulations, we used the standard 10 percent discount rate as suggested by the IMF. Although one may argue that there is a degree of subjectivity when choosing a certain “discount rate”, in today’s world, the discount rate probably should be much higher than 10 percent to reflect not only the standard set of risks that are debtor specific, but also systemic risks such as climate change, pandemic, food safety, etc. Taking systemic risks into account would mean higher forgiveness on NPV terms under rescheduling.

The World Bank and IMF have warned that the world economy is facing an increased risk of a global recession in 2023. Debt restructuring in such an environment requires global coordination, open-mindedness and compromises among all parties. Multiple innovative approaches can be considered including debt-to-bonds, debt-for-nature swaps (see the recent debt-for-conservation initiative by Barbados) and asset-plus refinancing. A delicate balance needs to be maintained between the needs for debt reduction in low-income countries, and the needs to maintain investor confidence in building public assets for a green and sustainable recovery.

*

阅读中文报告Never miss an update: Subscribe to the Global China Initiative Newsletter.