The Belt and Road Initiative and the Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment: Global Infrastructure Initiatives in Comparison

Infrastructure financing gaps in the Global South have widened in recent years with the need for addressing connectivity bottlenecks and climate-related challenges. To achieve the United Nations 2030 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), an additional $3.2 trillion or 2 percent of global gross domestic product (GDP) is needed annually for sustainable infrastructure investment, and roughly $700 billion per year of climate finance is required to reach net zero emissions by 2050.

How are China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and the Group of Seven (G7)-led Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment (PGII) positioned to further address widening infrastructure financing gaps in the Global South?

A new working paper by Oyintarelado (Tarela) Moses and Keren Zhu describes the development and compares the features of the BRI and the PGII, finding key similarities and distinct attributes that offer opportunities for short- or long-term collaboration and provide host countries with options for addressing infrastructure gaps.

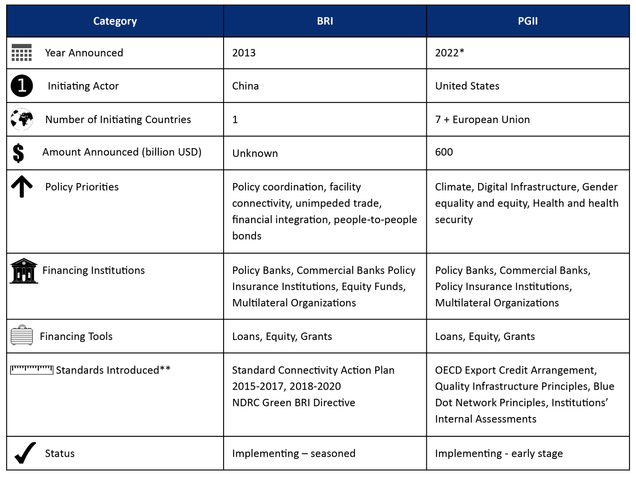

Table 1: Comparing the BRI and the PGII

*Although the PGII was established in 2022, its predecessor, the B3W was established in 2021.

**Not an exhaustive list of standards introduced.

Main findings:

- Focus on infrastructure development: The BRI and PGII both focus on supporting infrastructure development largely in low -to middle-income countries, allowing for joint contributions and boosting the amount of global public finance directed at infrastructure development if the PGII is to achieve its commitments.

- Evolution from intent to implementation: The initiatives also experienced a repackaging phase, from intent to implementation, after an amorphous and ambiguous stage.

- While it took two years to expand and interpret the announcement of the BRI into an implementable initiative, the PGII also evolved from an announcement of intent in 2021, packaged as the Build Back Better World (B3W), to an initiative with concrete goals and indications of more coordination.

- Rebranding of existing development assistant efforts: Both initiatives rebranded existing development assistant efforts, with China’s policy banks maintaining the same mandates to support Chinese companies and exports and G7 financing institutions fulfilling their mandates, but now branded as contributing to the PGII.

- Domestic growth as a prominent priority: Similarly, the BRI and PGII both prioritized domestic growth, with China’s leaders seeking to address industrial overcapacity, utilize foreign reserves and improve connectivity between China and the rest of the world, and the US planning to enhance American competitiveness in international infrastructure development and create domestic jobs.

- Utilization of public financing tools: Both initiatives utilized public financing tools, with the BRI largely relying on Chinese policy banks, a state-owned insurance agency, development funds and other lenders and the PGII encouraging finance from G7 public institutions.

- Focus on green development: The BRI and PGII focus on green development, as greening the BRI has become a policy priority in China and the G7 has prioritized supporting projects that address climate change needs.

- Hard vs. soft infrastructure projects: The BRI and PGII differ in their focus on hard versus soft infrastructure projects, as the latter focuses on “softer” outcomes, namely improvements in climate, health and health security, modernized digital technology and gender equity and equality. Meanwhile, China has over two decades of experience in building infrastructure overseas.

- Project and financing scale: Both initiatives also differ in their project and financing scale. The BRI has supported megaprojects, accounting for 55 percent of finance value ($158 billion of $287 billion) Chinese policy banks supported from 2013-2019, while the PGII tends to support small to medium scale projects.

- State finance versus private sector finance: Unlike the BRI, which mainly relies on public bilateral loans and investment backed by state-owned banks and funds, the PGII seeks to catalyze hundreds of billions of dollars in private-sector capital.

- Number of actors involved and level of coordination: Furthermore, the BRI and PGII differ in the number of actors involved and the level of coordination.

- The Belt and Road Construction Leadership Group, a state-level steering committee housed at the State Council led by a vice premier, coordinates BRI efforts between different ministries, agencies, provinces, development banks and SOEs.

- Meanwhile, the PGII has yet to generate an overarching, transnational, issue-specific coordination mechanism across all G7 countries. However, each G7 country appears to solely coordinate their own institutions’ contributions to PGII.

Given some overlapping similarities, institutions in the BRI and PGII should consider collaboration in the short- and long-term. However, if collaboration is not feasible in the short term, institutions in the BRI and PGII could pursue complementary competition. The researchers suggest recipient countries should leverage the differences in the initiatives to negotiate the best deal for their development projects.

Read the Working Paper Read the Blog 阅读中文版工作论文