“Blue-ing” the BRI: Mitigating the Marine Risks of China’s Overseas Development Finance

By Rebecca Ray

From 2020-2022, China has presided over the Council of the Parties of the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD COP). Their leadership has included the establishment of the Kunming Biodiversity Fund and the consideration of the Post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework.

Concomitantly, researchers at the Boston University Global Development Policy Center have been tracking the risks China’s overseas development finance and investment may pose to biodiversity, globally and through in-depth analysis in the biological and cultural diversity hotspots of Indonesia and the Amazon basin.

Covering over two-thirds of the world’s surface, oceans are a crucial focus for biodiversity conservation. A new journal article published in One Earth traces the risks to biodiversity, marine protected areas and Indigenous-use seas from China’s overseas development finance for coastal and marine projects around the world. We find that risks vary dramatically across countries and sector, yielding lessons for Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) host countries as they plan future projects.

A new world of marine and coastal projects – and their risks

In this new research, we located 114 development projects in 39 countries, financed by the China Development Bank (CDB) and the Export-Import Bank of China (CHEXIM) between 2008-2019. CDB and CHEXIM are China’s two most active development finance institutions (DFIs) in overseas sovereign lending. We then estimated the risk posed by each project to three types of sensitive areas: likely critical habitats for marine biodiversity, marine protected areas and Indigenous-use seas (marine areas that are crucial sources of food and livelihoods for Indigenous communities). These projects are shown in Figure 1, together with the impact risk they pose to near- and off-shore habitats.

Figure 1: Location (a) and Risk Levels to Habitats (b) of 114 projects financed by Chinese DFIs, 2008-2019

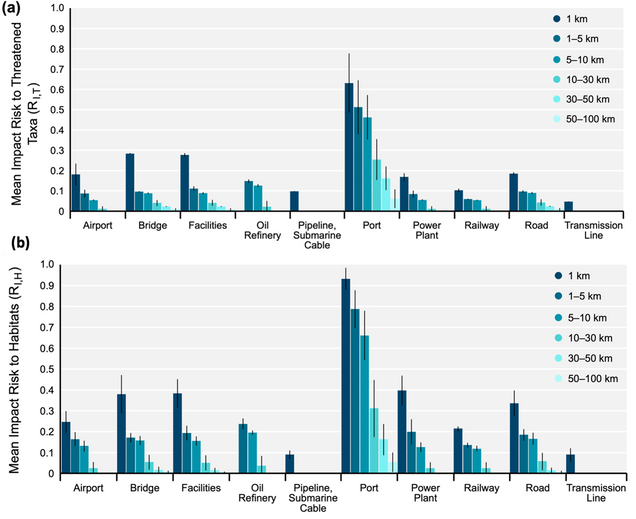

A wide range of risks are posed by different projects sectors, as Figure 2 shows. Ports carry much greater risks than other types of projects, due to a wide array of factors, including habitat disruption for construction, noise, light and invasive species transported with ships, among others. However, as Figure 2 shows, most types of project risks are limited to a few kilometers around the project site. Thus, project planners can mitigate risks by locating projects in areas with lower sensitivity or where economic activity is already high.

Figure 2: Average Risks to Threatened Taxa (a) and Habitats (b) from Chinese Overseas Development Finance Projects, 2008-2019

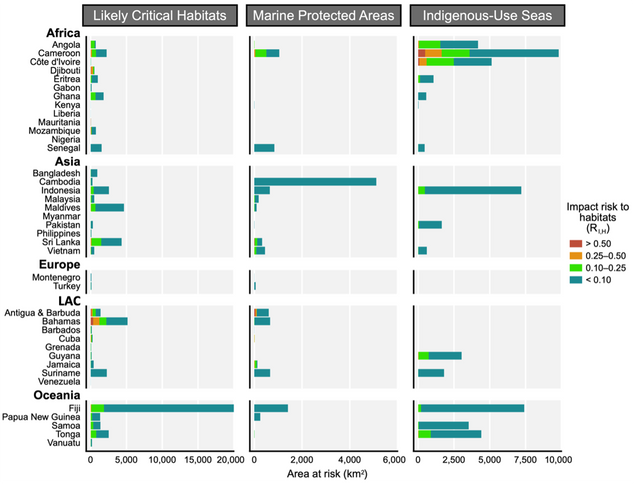

Risks also varied dramatically across countries, as Figure 3 shows. This wide variation is true even among neighboring countries whose coasts border on common marine habitats. African countries – particularly the Atlantic coasts of Angola, Cameroon and Côte d’Ivoire – show significant risks to Indigenous-use seas but lower levels of risk to likely critical habitats and marine protected areas. In Asia, Cambodia’s projects pose significant risk to marine protected areas and projects in Indonesia carry significant risk to Indigenous-use seas, while other Asian countries’ risks are much lower. Several countries in Oceania show significant risks from these projects to likely critical habitats and to Indigenous-use seas, but less to marine protected areas.

Figure 3: Total Ocean Area Facing High and Low Impact Risk to Habitats within Critical Habitats, Marine Protected Areas, and Indigenous-Use Seas from China’s Overseas Development Finance, 2008-2019

Policy lessons for Chinese and host-country planners

Project managers can opt for higher or lower risk levels through the types of projects they pursue, where they locate them and their varying national levels of environmental and social protections. The results reinforce findings from previous research on Chinese finance and investment globally and in the biodiversity hotspots of Indonesia and the Amazon basin: planners have considerable policy space to pursue sustainable and inclusive development through Chinese development finance.

For its part, China has made considerable recent strides in developing protections for outbound finance and investment. In 2021, guidelines issued by the Ministry of Ecology and Environment (MEE) and Ministry of Com

As China and host country governments continue to develop their environmental governance framework for international finance and investment, they would be wise to consider empirical evidence on biodiversity risk. Through greater information transparency for planners and stakeholders, green development finance can also be “blue” and protect marine habitats and the coastal communities they support.

Read the Journal Article*

Never miss an update: Subscribe to the Global China Initiative Newsletter.