For China’s Overseas Coal Plants, Early Retirement is an Economic and Political Imperative. Here’s How It Can Be Done

By Alex Clark and Cecilia Springer

Chinese development finance institutions (DFIs) are not alone in providing financing for coal-fired power plants – but they have played an outsized role in funding publicly-financed plants built outside China in the last ten years.

Under pressure from host countries’ climate commitments and competition from renewable power sources, early retirement of the 39 giga-watt (GW) fleet of currently-operating China-financed plants overseas urgently needs to be explored.

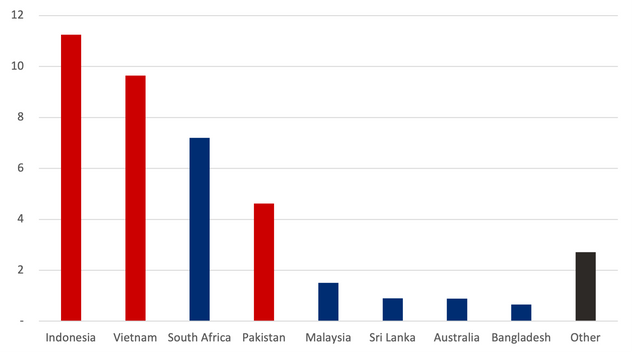

In South and Southeast Asia, most of the coal plants backed by Chinese public funders are concentrated in Indonesia, Vietnam and Pakistan, as shown in Figure 1. With average ages of seven, eight and four years, respectively, if these plants operated for their full intended lifetimes, they would breach the 2040 target for unabated coal phaseout featuring in the International Energy Agency’s Net Zero by 2050 scenario.

Figure 1: Overseas Coal Capacity Financed by Chinese Investors and Lenders (GW)

In a new working paper published by the Boston University Global Development Policy Center, we explore what is needed for China-financed coal plants in Indonesia, Vietnam and Pakistan to be retired early – and, more importantly, what roles their Chinese creditors and sponsors might play in that process. We find that at a conservative $100/ton price on avoided carbon dioxide emissions, retiring these plants ten years early could yield global economic and social benefits in excess of $200 billion, even without considering the benefits for local populations affected by coal mining, air pollution and water scarcity associated with the plants.

The costs of early retirement

Based on a cash flow model of a representative subcritical coal plant, we explore four possible routes to early retirement. Two approaches are based on concessional financing:

- Cash buyout: a full purchase, by a third party, of the debt and equity cashflows associated with the plant, after which the plant is retired immediately;

- Concessional finance: an interest rate subsidy paid to debt holders, combined with an equity return subsidy for equity holders, which allows the plant to stop operating earlier than planned, while still generating returns.

The other two options involve debt or equity holders “swapping” monetary cash flows for avoided carbon emissions (referred to elsewhere as “debt-for-carbon” or “debt-for-climate” swaps):

- Carbon buyout: a full buyout funded by revenue raised from setting a price on avoided carbon emissions;

- Concessional carbon finance: an interest rate/equity return subsidy funded by revenue raised from setting a price on avoided carbon emissions.

We find that using an interest rate subsidy allows a coal plant to be retired at lower cost than a full buyout, by allowing payments to be spread over time. For a subsidy starting five years into the plant’s operation, retiring the plant 20 years early would cost $151 million – 20 percent less than the equivalent buyout. Retiring it 15 years early would cost $46 million, just over half the buyout cost of $81 million. Moreover, the value placed on avoided future emissions required to fully fund the subsidy would be $12.5 per ton of CO2 to retire 20 years early, and $6 per ton to do so 15 years early. As the retirement date gets later and later, both the cost of the subsidy and the carbon price needed for pay for it, fall, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1: Summary of Costs of Early Retirement under Each Core Scenario, Assuming (for Scenarios 3 and 4) Implementation in Year Five of Plant Operation

In other words, subsidizing investors’ returns may be a better use of concessional funding than buyouts. This is especially true where sources of public and private finance are scarce and there is a need for large-scale investment in renewable capacity additions to replace coal and meet the electricity demand growth fuelling broader economic development. By using a subsidy mechanism, early retirements can be achieved without diverting more funds than necessary away from investment in desperately needed energy replacement capacity.

It also suggests that, for Chinese lenders and host governments alike, the price on carbon needed to justify a subsidy is very low. At around half of the $24/tCO2 social cost of carbon estimated for China in 2018, subsidizing early retirements could be beneficial to international financiers like China on the basis of reduced climate change damages alone. Doing so could also bolster the country’s international reputation as a backer of green development and expand export markets for renewable technologies to replace retired coal.

Obstacles to early retirement: The political economy of coal in Indonesia, Vietnam and Pakistan

If early retirement appears to make economic sense, why hasn’t it been done yet?

To answer this important question, we explored the political economy of the Indonesian, Vietnamese and Pakistani country contexts. In each case, power is concentrated among core domestic political actors (political parties, regulators and cabinet ministries) and brokers, constrained to differing degrees by the influence of electric utility companies and coal mining companies, state-owned or otherwise. In each case, coal plays a central role in delivering economic growth, energy security and electricity affordability – and is aided by structural features of power markets that work to protect the coal-focused status quo.

In concert, these factors act to significantly complicate any effort to pursue early coal retirement. But entry points do exist: political brokers’ influence is significantly tied to their ability to attract foreign capital, which in turn is tied to a trend towards financial liberalization in the energy sector. In this sense, allowing external actors to finance early retirement does not necessarily threaten the positions of key political and economic actors.

To stand a chance at success and avoid constraining domestic actors’ ability to finance renewable energy expansion, early retirement initiatives will require the active engagement of debt and equity holders in China, and by extension the Chinese government. Options available to China might include debt restructuring to reduce interest rates, transferring coal plant assets to a dedicated policy bank, fund, or asset management company within China or transferring these assets to international blended finance vehicles along the lines of the Asian Development Bank’s proposed Energy Transition Mechanism (ETM) model.

Policy implications

China’s DFIs have been the biggest public lenders to overseas coal in recent years – but they are also very well-placed to lead the early retirement of the very same plants. China may be unlikely to sign up to the Just Energy Transition Partnership (JETP) model backed by Western economies. However, from the debt perspective, China’s DFIs have a history of active engagement in debt restructuring, and debt-for-climate swaps are already under discussion in China as possible policy instruments for overseas financing. From the equity side, China has already created over 20 overseas development investment funds, with DFIs as shareholders, that serve to channel capital towards development goals and could act as institutional homes for coal assets targeted for early retirement.

Early retirement of coal plants is not a new idea – but it is an urgent one, and one that has not yet been applied to plants outside the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) that are backed by Chinese public funders. We argue that despite the political economy challenges associated with early retirement, promising and viable avenues do exist for retiring plants early. Time is of the essence in implementing cost- and carbon-saving approaches such as these to mitigate the worst effects of climate change and support energy transitions in developing economies.

Read the Working Paper*

Alex Clark is a PhD Researcher at the Smith School of Enterprise and the Environment, University of Oxford and a former Global China Research Fellow at the Boston University Global Development Policy Center (2021-2022). He works primarily on state-owned power companies and socioeconomic pathways for phasing out coal, with a particular focus on China.

Never miss an update: Subscribe to the Global China Initiative Newsletter.