6 Charts on Climate Impacts in 6 Central American and Caribbean Countries

By Samantha Igo

Within 24 hours in late October, Hurricane Otis, in defiance of forecasting models, increased windspeed by 115 mph and made landfall in Acapulco, Mexico as a Category 5 hurricane. In addition to the devastating loss of life, insurance analysts have estimated “insurable” losses in Acapulco and the surrounding area to be as much as $15 billion. In response, Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador recently announced a $4.3 billion reconstruction plan.

With experts pointing to the unusually warm water off the coast as a reason for the hurricane’s unpredicted and catastrophic escalation, Otis is a harbinger of the kind of storms that can be expected if the climate crisis remains unchecked. Particularly vulnerable regions, like Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC), are already bearing the brunt of these impacts, but simultaneously lack the fiscal space to effectively adapt to the impacts of climate change.

To understand the scope of these impacts, a new technical paper from a team of researchers at the United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean assesses the potential impact of climate change on growth and fiscal stability for six Central American and Caribbean countries: Barbados, Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras and Saint Lucia (CAC6). It is the latest in a series of technical papers published by the Task Force on Climate, Development and the International Monetary Fund, a global consortium seeking to advance a development-centered approach to integrating climate into operations at the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

The six charts below illustrate key findings from the paper, and the conclusion outlines policy recommendations for international financial institutions (IFIs) like the IMF.

Climate shocks are increasing in frequency and intensity

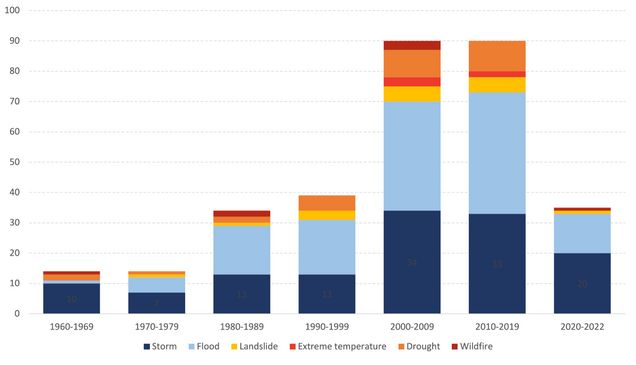

Chart 1: Meteorological, Hydrological and Climatological Disasters for CAC6, by Decade, 1960-2022 (Count)

Hurricanes are far from the only extreme weather impacting CAC6 countries. Floods, heat waves and extreme temperatures are particularly detrimental to countries that rely on agriculture for a significant part of their economy, such as El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras. Climate disasters have sharply increased since the 1990s, and in just two years – from 2020-2022 – there have been nearly as many climate events as CAC6 countries saw in a decade. What is more, losses from these disasters – staggering as they are – are rarely fully recovered.

Vulnerable countries lack fiscal space to respond to disasters

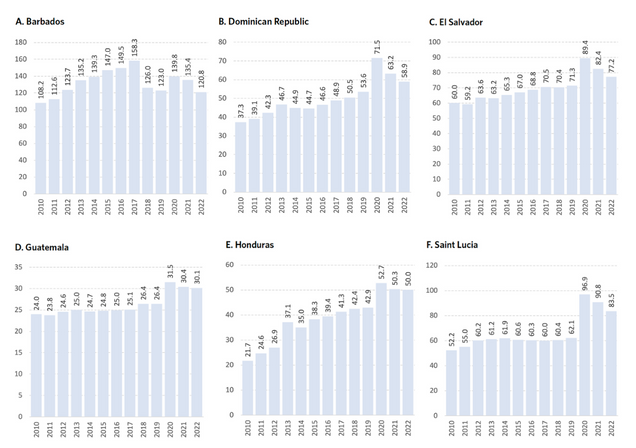

Chart 2: General Government Gross Public Debt, 2010-2022 (Percent of GDP)

Sovereign debt levels for emerging market and developing economies (EMDEs) have surged by 178 percent since 2008, and climate change threatens already ballooning debt levels. Chart 2 highlights government gross public debt for CAC6 countries since 2010. Notably, 2020 marks a sharp increase in debt in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, exemplified by a 34.8 percentage points of gross domestic product (GDP) rise in Saint Lucia. Repeated hurricanes in the years following and high social spending during the pandemic exacerbated already tight fiscal space: Hurricane Eta and Iota landed within two weeks of each other, and Hurricane Elsa resulted in estimated spending needs of 0.8 percent of GDP in Barbados. This figure underscores the unmitigated pressure countries are facing to address social needs while constantly rebuilding from – and paying for – climate disasters.

Climate shocks will slow already weak economic growth

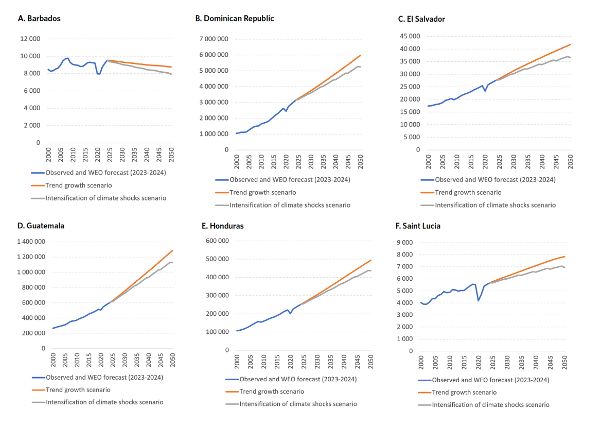

Chart 3: Gross Domestic Product, by Scenario, 2000-2050 (Millions of national currency at constant prices)

Chart 3 shows the consequences of increasing climate shocks for CAC6 countries on medium-term growth. The researchers estimate GDP in 2050 to be between 9 percent and 12 percent below the trend growth scenario (orange line). Not only will climate events of increasing intensity and frequency put pressure on growth, but economic activity will also be undercut by falling labor and agricultural productivity as temperatures increase.

Offsetting climate losses is possible but requires serious resource mobilization

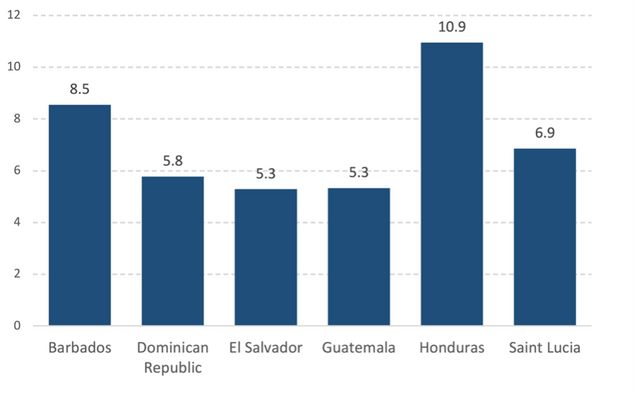

Chart 4: Estimated Average Annual Investment Needs to Fully Compensate for the Economic Losses under the Intensification of Climate Shocks Scenario Compared to Trend Growth Scenario (Percent of GDP)

While it is possible to offset climate losses in CAC6 countries, the resources necessary are substantial. Chart 4 shows that closing the gap between the ‘trend growth scenario’ and ‘intensification of climate shocks scenario,’ as seen in Chart 3, would require, on average, an additional investment of 5.3 percent of GDP to 10.9 percent of GDP per year. This level of investment would need to facilitate a structural transformation of the economy, and the authors note that investments in education, healthcare and other social protections will also be vital to achieving a low-carbon transition that is also just.

Achieving Nationally Determined Contributions can lead to explosive debt levels

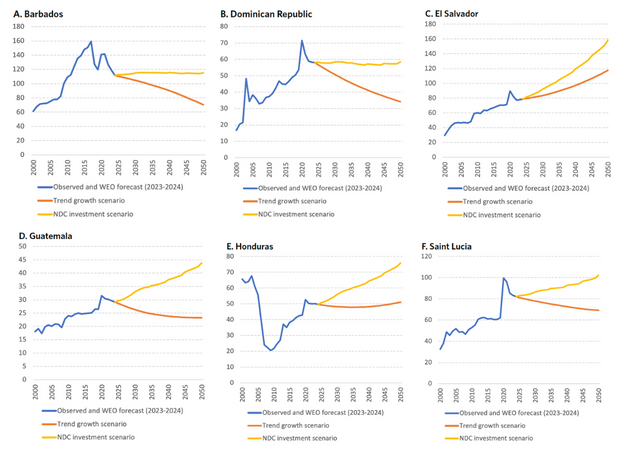

Chart 5: Central Government Gross Public Debt, by Scenario, 2000-2050 (Percent of GDP)

An investment push of a smaller magnitude, based on the mitigation and adaptation objectives outlined in the nationally determined contributions (NDCs) submitted by countries in the sample to the UN Framework Convention for Climate Change (UNFCCC), would only modestly limit economic losses from climate change. Already, the UNFCCC has emphasized that current NDCs are not sufficient to remain below the 1.5C threshold of global warming, and what is more, the first Global Stocktake, concluding at the 28th UN Climate Change Conference (COP28) in Dubai, is poised to underscore how countries are not meeting even these less ambitious goals. More ambition, and more finance, will be necessary to close that gap.

For CAC6 countries, however, Chart 5 shows that NDC investment can result in explosive debt trajectories, particularly for El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras and Saint Lucia, resulting in part from greater investment needs that are compounded by slower growth.

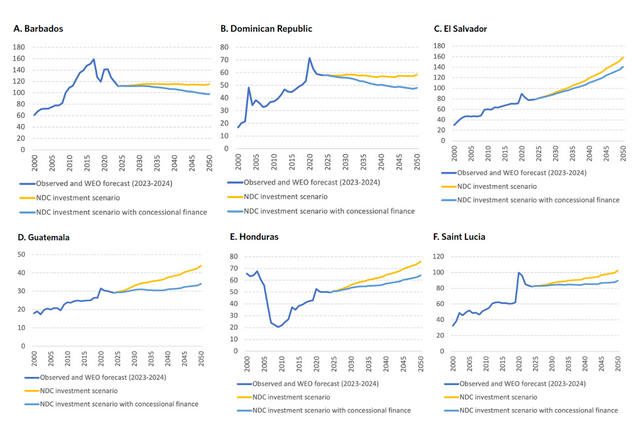

Concessional finance can curtail debt levels, but not completely

Chart 6: Central Government Gross Public Debt, by Scenario with Concessional Finance, 1990-2050 (Percent of GDP)

While challenging, achieving NDCs in CAC6 countries is not impossible. Chart 6 shows that reducing the cost of climate finance could reduce debt burdens, at least in the interim while countries mobilize additional resources domestically. In five of six countries, concessional finance mitigates the rise in debt levels in comparison to NDC investment without it (El Salvador’s debt remains unsustainable in either scenario). While concessional finance can soften debt trajectories, however, it cannot offer long-term debt sustainability on its own.

IFIs can support development-friendly climate investment

CAC6 faces not only a climate crisis but also a development crisis if certain policies and reforms across the international financial system aren’t enacted. First, debt relief is necessary for long-term debt sustainability for climate vulnerable countries. Debt interest payments are massive drains on public coffers, with interest payments on existing public debt amounting to more than 30 percent of social spending for some CAC6 countries.

Second, in addition to concessional finance, current climate financing from multilateral and national development banks to the region falls short. The authors argue that a capital increase at these institutions would provide more climate finance firepower.

Third, the IMF, as the only multilateral institution charged with maintaining global financial and fiscal stability, is uniquely positioned to facilitate low-carbon transitions without sacrificing development. The IMF can do this in three ways: first, its lending toolkit, and in particular the Resilience and Sustainability Trust, must be scaled commensurate with current need and calibrated to support an investment-led approach to a low-carbon transition. Second, the IMF can provide valuable technical assistance to country governments. This technical know-how could help build long-term, socially oriented investment strategies as countries navigate their low-carbon transition. Finally, the IMF can bolster its surveillance activities by moving beyond carbon pricing in its Article IV reports. The IMF could help countries implement a suite of climate policy instruments that matches their macroeconomic contexts.

The costs of building an inclusive, climate resilient future are undeniably great. The costs of not investing in this future, however, are far greater.

*

Read the Technical Paper Lee el blogNever miss an update: Subscribe to the Task Force Newsletter