How Central Bank Swaps Reinforce Inequalities in the Global Financial Safety Net

By Marina Zucker-Marques, Laurissa Mühlich, Barbara Fritz, Thomas Goda

What once consisted of only the International Monetary Fund (IMF) has become a complex, multilayered and non-coordinated network of institutions aimed at supporting countries during times of financial distress.

This network is known as the Global Financial Safety Net (GFSN), and comprises the IMF, regional financial arrangements (RFAs) and bilateral credit lines provided by central banks called currency swaps.

However, this network is more robust for some countries than for others. What determines if a country can count on sufficient and easy-to-access liquidity in a crisis, or if inadequate access to the GFSN jeopardizes or even worsens their capacity to financially recover?

Since the 2008 global financial crisis, central bank swaps have emerged as an increasingly important pillar of the GFSN, yet, scholarly attention on swaps is new and largely prioritizes either swaps by the US Federal Reserve (Fed) and the People’s Bank of China (PBOC), despite an increasing diversity of swap providers.

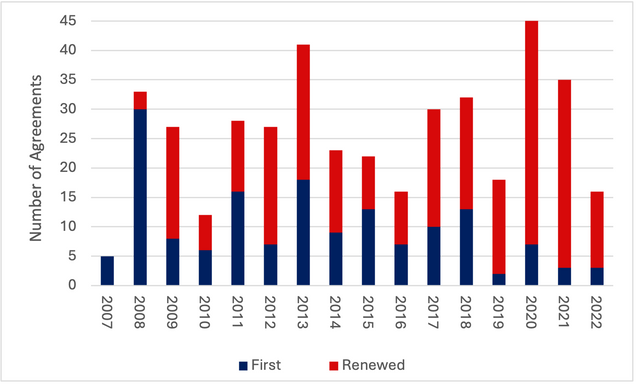

To that end, our new working paper examines what factors determine which countries receive and provide swaps beyond the Fed and PBOC. It draws on the Global Financial Safety Net Tracker – a data interactive developed by Boston University Global Development Policy Center, Freie University Berlin and the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) that measures the annual lending capacity of the GFSN – as well as additional information from central banks. In our working paper, we use a novel swap dataset of 410 currency swap agreements, covering 194 recipient countries from 2007-2022, as shown in Figure 1. The analysis focuses on crisis indicators, country-specific variables and bilateral relations.

Figure 1: Distribution of Swap Agreements Over Time, 2007-2022

Note: This figure depicts the evolution of bilateral swap agreements over time, distinguishing between first and renewed agreements.

It has been argued that the PBOC acts as quasi-lender of last resort through swaps. Our empirical analysis reveals that compared to other central banks, both PBOC and the Fed act as quasi-international lenders of last resort. Our study finds that a country’s income level plays a more significant role in securing access to swaps than the occurrence of a financial crisis or external debt levels. Advanced economies are more likely to receive swaps during crises, while middle-income and low-income countries often find themselves excluded from this element of the GFSN.

The key findings provide further insight into the resilience and degree of exclusivity of the international financial architecture, highlighting the need to ensure adequate support for all countries during times of financial distress.

Economic development as a key determinant

In line with other studies, we find that a country is more likely to receive a currency swap if it has a higher level of economic development, economic size and credit rating, as well as if it has a trade agreement and is geographically close to the country of the swap-providing central bank.

However, the analysis finds a stronger likelihood of receiving a swap depending on a country’s level of economic development than other papers which usually draw on much smaller data samples. We find that advanced economies – characterized by higher income levels, larger economic sizes and better credit ratings – are far more likely to receive these swaps.

Surprisingly, this trend persists even during financial crises, suggesting that in times of financial turmoil, wealthier nations are prioritized over those in greater need. For instance, during the 2008 global financial crisis, advanced economies like those in Europe and North America were able to access swaps faster and with significantly higher volumes than middle-income countries in Asia or Latin America.

Low-income countries, which arguably have the most to gain from such financial support, are almost entirely excluded from swap arrangements. This exclusion highlights a significant gap in the GFSN and raises questions about the inclusivity and fairness of global financial support mechanisms. Our findings underscore the need for a more equitable distribution of resources in the GFSN.

The role of major swap providers

The study further examined the role of major swap providers, particularly the Fed and the PBOC. Compared to other central banks, such as the European Central Bank (ECB), the Bank of Japan and other advanced economy central banks, these two are significantly more likely to provide currency swaps to countries experiencing financial crises and those with rising levels of external debt.

Yet, there are distinctions in PBOC and Fed influence, notably that developing countries access swaps mostly from China. Approximately 80 percent of swap provisions to developing countries come from China, and nearly 40 percent of China’s swaps are directed towards other developing nations. In contrast, the Fed’s swap agreements are highly selective, with a notable concentration on advanced economies. The most relevant central banks – such as the ECB and the Bank of England – benefit from unlimited swaps lines (both in time and volume) with the Fed, and we found only two Fed swaps to emerging economies, Mexico and Brazil, during the period we analyzed. The differing behaviors of these two central banks highlight the geopolitical dimensions of currency swaps and their implications for global and regional financial stability. Notably, relying on a geopolitically driven supply of emergency finance – as often is the case with swaps – can marginalize countries that need access to emergency finance and jeopardize not only the country’s own economic stability, but potentially also that of closely connected countries.

Interaction with IMF lending

An intriguing aspect of the study is the interaction between central bank swaps and IMF lending. We found that access to unconditional IMF lending is related to a lower probability of receiving a central bank swap, indicating a potentially more complex interaction between different elements of the GFSN. The IMF’s role as a crisis lender appears to influence the decisions of central banks regarding swap agreements.

At the same time, we find that membership in RFAs does not significantly influence provision of swap agreements. This nuanced understanding points to the need for better coordination among GFSN elements to ensure more equitable and effective support during financial crises. The current lack of integration between these elements can lead to inefficiencies and gaps in support, particularly for developing countries that might not have access to all layers of the GFSN.

Implications for global financial stability and policy recommendations

The study’s findings have profound implications for global financial stability and the effectiveness of the GFSN. The exclusion of low-income countries from currency swaps and the limited access for middle-income countries compared to high-income countries during crises reveal a systemic bias against poorer nations. The reliance on a few central banks as quasi-lenders of last resort, namely the Fed and the PBOC, also poses systemic risks. As central banks prioritize their national interests over global stability in their decisions to bilaterally support other central banks with liquidity in their own currency, global financial stability and crisis management increasingly depends on the preferences of big economies, rather than providing global financial stability as a public good.

We put forward two key policy recommendations to address the exacerbated global inequalities in the GFSN.

First, there must be enhanced coordination within the GFSN. While the IMF and RFAs have made progress, at least in terms of transparency and information sharing in recent years, swap-providing central banks do not coordinate their actions with the other GFSN elements. Thus, central banks should be brought to the table for better coordination in the GFSN, namely with RFAs and the IMF. This coordination should go beyond information sharing; it should also align lending activities to ensure comprehensive and timely support during financial crises. Recently, the IMF initiated a review of its policy coordination, underscoring the necessity for strong coordination to enable countries to access different layers of the GFSN.

Second, the IMF should expand its unconditional lending, particularly for developing economies that are excluded from swaps and lack sufficient RFA finance. Enhancing the timeliness and volume of unconditional crisis finance for solvent developing countries would level out the disparities in the GFSN and improve crisis resilience. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the IMF demonstrated that it can allow higher unconditional lending to low-income countries. This approach would create a more inclusive safety net, prevent the marginalization of multilateral crisis finance mechanisms and ensure that all countries, regardless of their income level, can access the support they need during systemic shocks.

Barbara Fritz is a professor at the Freie Universität Berlin, with a joint appointment at the Department of Economics and the Institute for Latin American Studies.

Thomas Goda is Professor of Economics at the School of Finance, Economics and Government at Universidad EAFIT (Medellin, Colombia).

*

Read the Working PaperNever miss an update: Subscribe to the Global Economic Governance Initiative Newsletter.