Does Global Crisis Finance Sustain a Middle-income Trap? Insights from the Updated Global Financial Safety Net Tracker

By Laurissa Mühlich, Barbara Fritz and William N. Kring

Following the COVID-19 pandemic, low- and middle-income countries (LICs and MICs, respectively), and in particular lower MICs, have recovered more slowly than high-income countries (HICs). LICs and MICs continue to struggle with tighter fiscal constraints in a period when they should be scaling up investments to tackle climate and development challenges.

These countries are also saddled with high debt service obligations, leaving insufficient fiscal space to pursue critical health and social spending. Such policy measures could be necessary in the event of a crisis to react to external shocks, like another pandemic, as well as sustain macroeconomic stability and economic development. Without sufficient access to crisis finance, financial instability will remain high and development prospects could remain bleak for both LICs and MICs.

Such crisis finance is provided by the network of institutions and arrangements collectively referred to as the Global Financial Safety Net (GFSN), which includes the International Monetary Fund (IMF), regional financial arrangements (RFAs) and central bank currency swaps.

The GFSN makes up a cornerstone of the global financial architecture, and the GFSN Tracker – a first-of-its kind data interactive co-produced by the Boston University Global Development Policy Center (GDP Center), Freie Universität Berlin and United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) – maps current and historical lending through the GFSN.

The interactive, newly updated with data through April 2024, underscores that, while the scale of available crisis financing from the GFSN has increased in the past decade – predominantly through an increase of number and volume of bilateral central bank currency swaps – inequitable access to short-term crisis finance persists in the aftermath of the pandemic.

Yet, easy access to voluminous GFSN crisis finance is crucial for MICs and LICs to sustain economic growth and facilitate the fiscal space necessary to invest in shared development and climate goals. To achieve an equitable and responsive GFSN, we present three policy recommendations: reforming the IMF’s quota system, vastly scaling up IMF resources and enhancing collaboration across elements of the GFSN – in particular central bank swaps.

Lower income groups face crisis finance gaps and limited fiscal space

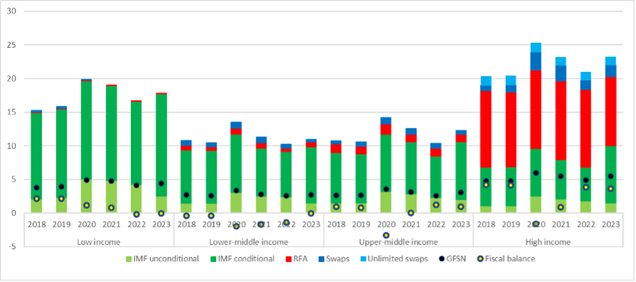

While the COVID-19 pandemic led to an increase in access to the GFSN for LICs and MICs, as shown in Figure 1, lower access to unconditional crisis finance is now the prevailing trend for lower and upper MICs (LMICs and UMICs, respectively). MICs have the least access to crisis finance resources from the GFSN, being able to access resources equivalent to only 3 percent of GDP in 2023. In contrast, HICs could access about 5.3 percent of GDP in 2023.

Figure 1: Access to the GFSN and fiscal balance as share of GDP, in %

The disproportionately lower GFSN access that MICs have is compounded by the fact that MICs also suffer from severe challenges to macroeconomic stability and economic development, including debt interest payments, as discussed above.

Given these constraints, MICs and LICs can expect to receive very little liquidity access from the GFSN should an external shock hit. In fact, for LMICs in particular, financing from GFSN resources would not even cover a government’s public debt service payment obligations, and countries would not have access to sufficient resources to support economic growth.

The IMF remains under-resourced in the GFSN

Currently, the IMF makes up the smallest portion of the GFSN. Despite calls for a fundamental reform to the Fund’s quota system, there was no net increase to the IMF’s lending capacity in the recent 16th General Review of Quotas nor a realignment of the IMF’s quota system with current economic realities.

Despite the approval of a 50 percent increase in IMF quotas, there will be proportional reduction of other sources of IMF finance, including the New Arrangement to Borrow (NAB) – a voluntary supplementary financial funding from shareholders. Hence, IMF lending firepower will remain constant despite the quota increase. Moreover, the ‘equiproportional’ quota increase that was announced in December 2023 means that new quotas are to be allocated based on a country’s current quota share, which perpetuate the inequitable distribution of resources across the GFSN.

As they stand now, IMF lending facilities are not capable of closing the crisis finance gap. In fact, if the Fund were to increase external crisis finance access for LICs and MICs to the level of HICs, IMF lending capacity would need to increase by $550 billion (or 127 percent of quotas).

IMF Managing Director Kristalina Georgieva has recently called on the G20 to make the international financial architecture “stronger, more equitable, more balanced, and more sustainable, so millions more can benefit,” and this must include the IMF vastly scaling up financial resources and reforming lending facilities to appropriately address the GFSN crisis finance gap for LICs and MICs.

Central bank currency swaps: Inequality in the GFSN does not come by chance

In contrast to the IMF, central bank currency swaps are the largest element of the GFSN with about $2 trillion active swap agreements annually since 2018. However, despite the volume, a new working paper shows that access to central bank currency swaps is highly uneven and biased against MICs and LICs. In fact, LICs are entirely excluded from swaps while they are the predominant crisis finance instrument of HICs.

In order to increase crisis resilience globally and for vulnerable countries in particular, addressing inequalities in access to currency swaps is crucial and will require closer coordination between all GFSN elements.

Starting points for this already exist, such as the IMF’s Policy Coordination Instrument (PCI). Yet, IMF-RFA coordination in this realm is exercised mostly in terms of information exchange, rather than formal coordination of lending programs and terms. Swap providers remain, however, completely outside of this coordination. Any coordination effort requires including major swap-providing central banks to enable countries’ access to different GFSN elements as well as to optimize its use. A transparent and predictable institutionalization of swap agreements would help address the inequality and inequity in the GFSN.

How to avoid a middle income trap in crisis finance

Based on the latest data from the GFSN Tracker, we present three recommendations for a more equitable and inclusive GFSN. First, the IMF must reform its quota system to bring it in line with 21st century economic realities. Doing so would help address existing inequities in its key decision-making structure and enhance the IMF’s legitimacy as an international financial institution.

Second, reform of the quota system must include a substantial increase in resources, resulting in more access to timely, voluminous crisis finance for LICs and MICs. This can also be done by overhauling IMF conditionalities to better align them with countries’ needs as well as increasing the volume and scope of non-conditional IMF shock facilities. There is precedence for this, as the IMF took such measures during the COVID-19 pandemic, and it did not risk the Fund’s sustainability but moved overall GFSN access limits for LICs and MICs upwards. Doing so would also make crisis finance more flexible for LICs and MICs, which is something these countries do not currently have given their lack of access to currency swaps.

Third, coordination of lending across different elements of the GFSN should be intensified. Prior collaboration between the IMF and RFAs has demonstrated that such coordination is possible, but particular attention must now be paid to central bank currency swaps, which remain vastly unequal in their usage.

As climate change shocks worsen and the deadline for the UN 2030 Sustainable Development Goals closes in, providing LICs and MICs with as many tools as possible to expand fiscal space, make the necessary investments and recover quickly from external shocks is critical for not only the future of these countries, but the future of the global economy as a whole.

Barbara Fritz is a professor at the Freie Universität Berlin, with a joint appointment at the Department of Economics and the Institute for Latin American Studies.

*

阅读博客文章Never miss an update: Subscribe to the Global Economic Governance Newsletter.