Rhetoric or Reality? Accounting for Diversity at College Career Fairs

By Neha Gondal

A college degree pays, but where one goes to college also makes a huge difference to lifetime earnings.

Attending elite schools significantly increases one’s chances of obtaining a well-paying job and, hence, economic and social success, which reproduces existing disparities.

Accordingly, college career fairs, which expose students to potential employers, serve as a critical filtration mechanism in this process. Far from being rare, career fairs are used as a recruitment tool by over 90 perfect of US firms. Given this ubiquity, what role do such events play in mitigating or reinvigorating job market inequalities?

On-campus recruitment fairs can, in theory, mitigate inequalities in the market for first jobs for college graduates, as they can be more egalitarian than alternatives like exclusive relationships between companies and colleges.

Yet, in a new study published in Socio-Economic Review, my co-author, Kristen Tzoc and I show that, far from alleviating them, campus recruitment fairs contribute to reproducing and possibly even worsening status, race and economic inequalities.

Adopting an innovative approach, we conceptualize recruitment partnerships between higher education institutions and accounting firms as a ‘social network,’ defined as relationships between and among individuals and/or organizations. This is a departure from much prior work, which has mostly relied upon ethnographic techniques to investigate such partnerships. A network lens is useful for investigating structural patterns of inequality at the field level, which are less evident through other techniques.

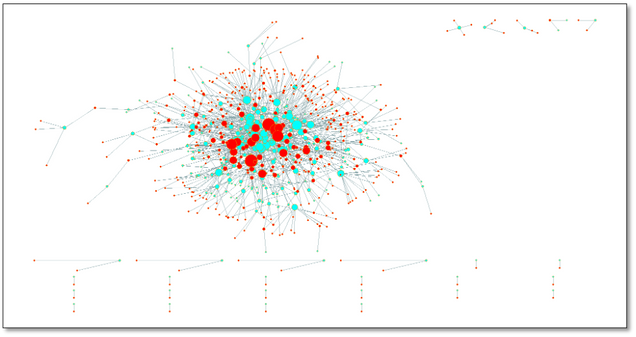

Figure 1 from our study shows the network of relationships between 250 higher educational institutions (blue nodes) and 445 accounting firms (red nodes) that comprise our data. Organizational nodes are sized by number of partnerships. The figure shows considerable popularity-based inequality: the center of the large component in the middle of the graph is dominated by several large-sized nodes indicative of high connectivity. The periphery, in contrast, shows that most nodes have few affiliations. The inset shows dense interactions between the leading organizations, based on reputation, in each field.

Figure 1: Visualization of the School-Firm Recruitment Network

Note: Blue nodes represent schools and red ones are firms. Inset shows interactions between the leaders in each field.

These two patterns – the division of interactants into a ‘core’ and ‘periphery’ and closure among the elite – are classic representations of inequality, especially based on status distinctions, in social networks.

The creation of a core of popular actors is frequently attributed to an interactional tendency referred to as ‘preferential attachment’ – a desire of actors to form connections with others that are popular or attractive for other reasons, such as prestige. Elite organizations are preferred partners in interaction because actors want to do business with others they believe will offer them products of high quality. However, quality can be difficult to observe, so social status distinctions are used to intuit worth. Preference for high-status actors also occurs because such alliances can be used to signal one’s own status. This is because status is widely understood to ‘leak’ or transfer through interactions from those that possess more to those who have less: we gain more status by having relationships with those who are well-known. Dense interaction between elites, as shown in the inset, is also typical of social networks characterized by deep inequality: elites prefer to interact with others of comparable status because it helps to consolidate and preserve their social standing.

We analyze this network using exponential random graph models (ERGMs), a statistical framework for modeling social networks. Our results show that elite schools mostly partner with prestigious firms. Elite accounting firms, in contrast, partner with reputed schools, but are also more open to forming alliances across the status spectrum.

While this relative openness of elite companies may suggest organizational efforts at addressing inequalities based on school prestige, our research also shows that elite firms are nevertheless engaged in other forms of reputation-based discriminatory recruitment: they hire for their rank-and-file positions from less well-known schools and for their choice roles from prestigious ones.

Significantly, we also find that elite firms are less likely to form partnerships with schools that have high proportions of African American students majoring in accounting. And, despite a history of poor representation of women in the industry, firms make no special efforts to recruit from schools that have a high concentration of women accounting majors. Colleges behave similarly—schools with large endowments are less likely to partner with firms that have African American leadership and schools make no special effort to partner with companies that have women in leadership positions.

The remarkable thing about these findings is not that elite organizations continue to pursue prestigious partners — that is not unexpected considering the status consciousness of both industries. It is how little they are doing to mitigate inequalities in their relationships, despite public commitments to enhance organizational ‘diversity.’ The pursuit of racial and gender diversity has been a valued and, arguably, publicly valorized goal at higher education institutions and corporations for several decades.

Yet, there is a noteworthy distinction between the two types of organizations in this regard. Diversity of employees and, consequently, mechanisms for its implementation through recruitment are culturally institutionalized and even legislated in the context of firms. Indeed, workforce diversity has been rhetorically embraced in the accounting industry. Diversity has also been heterogeneously framed to include race, gender and educational credentials. As in other fields, inclusiveness on educational credentials, so-called ‘university-blind’ recruitment is targeted at alleviating access and income inequalities associated with the prestige of one’s college degree.

In contrast, there are neither cultural nor legal imperatives impelling higher educational institutions to partner with firms that are deemed to be diverse in the context of student employment. Distinguishing it from recruitment or ‘upstream diversity,’ we introduce a new term, ‘downstream diversity,’ to refer to this latter form of inclusiveness. The lack of institutionalization of downstream diversity should lead elite colleges to prioritize the pursuit of prestigious alliances relative to partnerships with diverse firms, which is precisely what we find.

Considering publicly professed workforce diversity goals, social pressures to conform with peers and desires to avoid lawsuits, recruiting firms, in contrast, should be more motivated to form relationships with schools that are demographically diverse. Our findings that firms are more open in their partnerships with educational institutions than schools are with firms are consistent with this differential effect of diversity. Yet, our remaining findings that elite firms avoid schools with high representation of African American students and fracturing of job profiles based on school status problematize this interpretation. As such, our findings suggest that, despite both types of organizations making strong and public commitments to diversity, neither is making good on those promises.

While the failure of accounting firms to implement their commitments to diversity is indisputable as per our findings, the lack of institutionalization of downstream diversity does not absolve higher educational institutions altogether. Higher education in the United States has been contending with historic inequalities in academia for decades.

In this context, turning a blind eye to downstream diversity—either strategically or inadvertently—is no less of a failing. Failure to incorporate diversity in student placements is a blind-spot in higher education — if not a failure of implementation, then certainly one of imagination. One policy implication of our research is that academia needs to incorporate down- stream diversity initiatives into their repertoire of diversity management strategies. On the other side, our work suggests that firms need to take their recruitment diversity policies seriously, not only at the individual level, but also at the system-level. Firms, especially elite ones, need to make serious efforts at recruiting from less reputed schools as well as institutions with high representations of racial, ethnic and gender minorities.

*

Read the Journal ArticleNever miss an update: Subscribe to the Human Capital Initiative newsletter.