China, Latin America and the Caribbean Deepen Ties as Chinese Firms Shift to Direct Investment and Infrastructure

By Rebecca Ray

In 2023, Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) and China continued to deepen their economic relations, with a record number of presidential visits and continued strength in Chinese investment and infrastructure in LAC.

These are among the findings of the 2024 edition of the China-Latin America and the Caribbean Economic Bulletin, published by the Boston University Global Development Policy Center (GDP Center) and providing a synthesis of the latest trends in the China-LAC economic relationship.

In particular, 2023 saw LAC presidents articulate their priorities for the future of the relationship, with a particular focus on infrastructure, commodity exports and renewable energy supply chains. These priorities appear to be borne out by the trends in the economic relationship, which buoyed three sectors in particular: beef exports, transition mineral extraction and rail infrastructure.

China-LAC: Setting the economic policy agenda

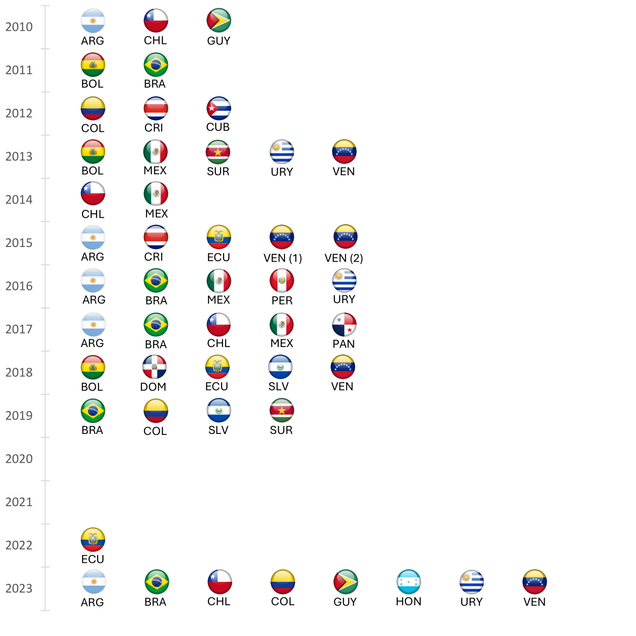

A record eight LAC presidents traveled to China in 2023, after just one such visit in 2022 and none in 2020 or 2021. As Figure 1 shows, this included presidents from countries that have visited China frequently, such as Argentina, Brazil and Venezuela, those that have visited only once or twice in the past such as Colombia, Guyana and Uruguay, as well as Honduras, which only recently established diplomatic relations with Beijing.

Figure 1: LAC Presidential Visits to China, 2010-2023

Note: ARG: Argentina; BOL: Bolivia; BRA: Brazil; CHL: Chile; COL: Colombia; CRI: Costa Rica; CUB: Cuba; DOM: Dominican Republic; ECU: Ecuador; GUY: Guyana; MEX: Mexico; PAN: Panama; PER: Peru; SLV: El Salvador; SUR: Suriname; URY: Uruguay; VEN: Venezuela

LAC presidents used these visits to further their policy goals, frequently touching upon the same themes. Table 1 lists the most common agenda topics, including the sectors that have long formed the backbone of the China-LAC relationship such as infrastructure and commodity exports, as well as newly relevant themes like renewable energy, transition minerals and green development.

Table 1: Agendas of LAC Presidential Visits to China, 2023

Overall economic trends

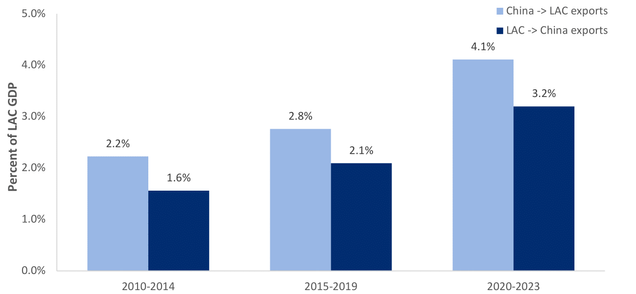

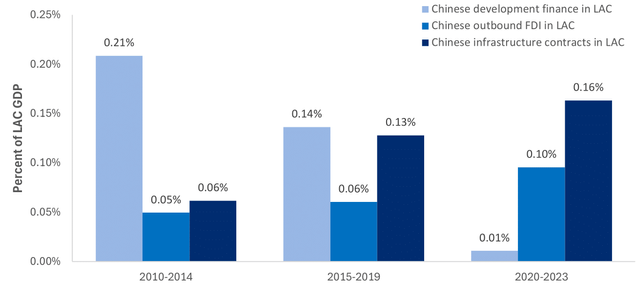

As in previous years, the 2024 China-LAC Bulletin tracks trends in China-LAC merchandise trade as well as Chinese outbound foreign direct investment (OFDI) and development finance in LAC. In addition, the 2024 edition introduces Chinese firms’ infrastructure contracts in LAC. Taken together, these trends present a nuanced view of the China-LAC economic relationship. Figure 2 shows the scale of each of these types of activities as a share of LAC gross domestic product (GDP) since 2012 (Figure 2 uses four-year periods to denote the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020.) Figure 2A shows merchandise exports between LAC and China: LAC exports to China have doubled as a share of regional GDP, while China’s exports to LAC have risen by 70 percent.

Figure 2B presents trends in development finance, OFDI and infrastructure contracts. As Figure 2B shows, development finance has fallen dramatically, while direct infrastructure contracts have risen by nearly the same amount that development finance has fallen. Indeed, over the last four years, infrastructure contracts amount to nearly the same share of LAC GDP as development finance once did a decade ago. Chinese OFDI has remained strong, maintaining pace with regional economic growth and accounting for about one-third of 1 percent of regional GDP.

Together, these trends may signal a maturing relationship. As Chinese firms gain experience operating in LAC, they have become more willing to work directly as contractors and investors, rather than depending on the intermediation of China’s development finance institutions (DFIs).

Figure 2: China-LAC Economic Activity Relative to LAC GDP, 2012-2023

2A. China-LAC Merchandise Trade Relative to LAC GDP, 2012-2023

2B. Chinese development finance, infrastructure contracts and OFDI in LAC, 2012-2024

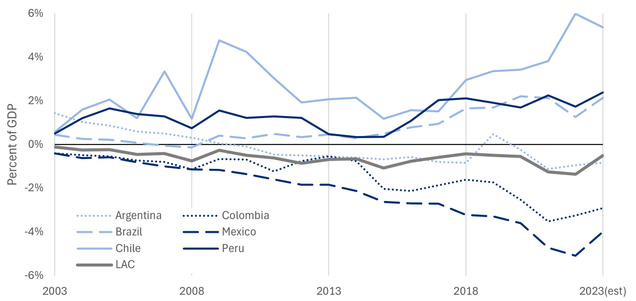

Trends in China-LAC merchandise trade

For the first time in eight years, China’s merchandise exports to the world fell in 2023, including those to LAC. As a result, LAC’s merchandise trade deficit with China moderated somewhat in 2023 to approximately 0.5 percent of regional GDP. Most major economies also saw improving trade balances with China in 2023, as Figure 3 shows. The exception to this trend is Chile, whose merchandise trade balance with China fell amidst Chile’s temporary decline in copper production in 2023, although copper output has since rebounded. Overall, major mineral and agricultural commodity exporters Brazil, Chile and Peru continue to show trade surpluses with China of over 2 percent of their GDP, while Colombia and Mexico face trade deficits with China of a similar magnitude, and Argentina finds itself with a more moderate trade balance with China, which usually varies between -1 and 1 percent of GDP.

Figure 3: Merchandise Trade Balance with China: LAC and Six Major LAC Economies

LAC’s exports to China continue to be concentrated in agricultural and mineral commodities with little value added: just five products accounted for 67 percent of LAC-China exports from 2020-2023. In fact, the dominance of low-technology sectors may have intensified somewhat in 2023, as frozen beef rose into the top five LAC-China exports for the first time, displacing refined copper. LAC-China beef exports have doubled in volume in the last five years and roughly quintupled in the last decade, and LAC now accounts for over 75 percent of China’s beef imports. LAC-China exports of transition minerals such as lithium and copper ores and concentrates (the unrefined state of the metal) continue to grow as well, with LAC-China exports accounting for roughly half of all global trade of these products. LAC-China lithium exports, in particular, have quintupled in volume since 2020.

Trends in Chinese OFDI in LAC

New to the 2024 edition of the China-LAC Bulletin is an enhanced analysis of Chinese OFDI in LAC, using data from the Red Académica ALC-China’s annual “Monitor of Chinese OFDI in Latin America and the Caribbean.” This dataset has the advantage of each project being manually verified and recorded in the year when activity began rather than when investors initially announce their intentions for new projects. Incorporating this data source allows insight into the timing of investment activities in the region.

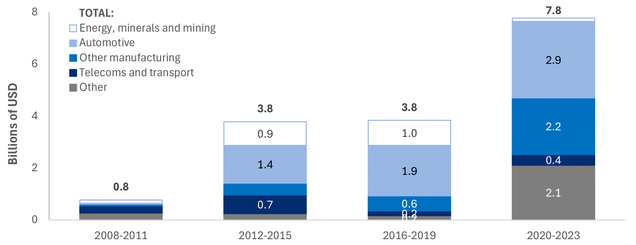

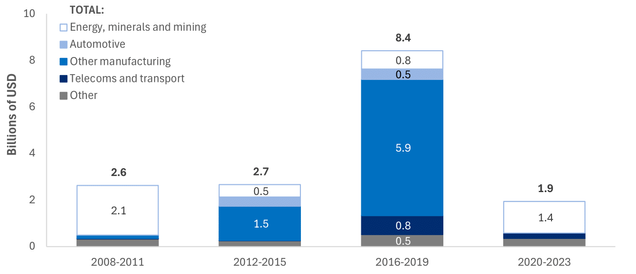

Despite the global economic slowdown and uneven recovery since 2020, new (greenfield) Chinese OFDI projects in LAC grew to record levels from 2020-2023, as Figure 4 shows. The profile of these investments remains starkly different in different sub-regions of LAC: Figure 4 shows South America (in Figure 4A) separately from Mexico, Central America and the Caribbean (in Figure 4B). Although the Mexican economy predominates in the latter category, the sectoral composition is similar throughout that sub-region.

As Figure 4A shows, Chinese OFDI in South America is traditionally concentrated in the sectors of energy, minerals and mining, which attracted nearly all China-South America greenfield OFDI since 2020. However, as Figure 4B shows, Chinese greenfield OFDI in Mexico, Central America and the Caribbean is more tilted toward manufacturing, particularly automotive manufacturing (and especially in electric vehicles). In fact, although this sector has garnered significant attention recently, it has been the most important sector for Chinese greenfield OFDI in Mexico, Central America and the Caribbean since 2015.

Figure 4: Chinese Greenfield OFDI in LAC

4A: South America

4B: Mexico, Central America and the Caribbean

In 2023, the largest Chinese greenfield investments in LAC include:

- Solarever’s $1 billion investment in electric vehicle manufacturing in Mexico.

- Chengxin Lithium Group’s $823 million investment in the SDSA lithium project in Argentina.

- Huawei’s $800 million investment in smartphone manufacturing in Brazil.

- Zijin Mining Group’s $600 million investment in Argentina’s Tres Quebradas lithium project.

- Ningbo Xusheng Group’s $350 million investment in a new electric vehicle plant in Mexico.

- Minerals and Metals Group’s (MMG’s) investment of $350 million to expand its Las Bambas copper mine in Peru.

- BYD’s investment of $290 million in a lithium cathode factory in Chile.

Figure 5 explores the other avenue of OFDI: mergers and acquisitions (M&As). Overall, show a mostly similar trend to the greenfield OFDI described, with one notable exception: Chinese M&A investment in Mexico, Central America and the Caribbean has dried up dramatically since 2020, particularly in the manufacturing sector. Thus, China’s manufacturing OFDI in this sub-region has changed qualitatively, switching from a preference for M&As, to greenfield projects.

Figure 5: Chinese M&A OFDI in LAC

5A: South America

5B: Mexico, Central America and the Caribbean

In 2023, the largest Chinese M&A investments in LAC include:

- State Grid Corporation of China’s purchase of Enel Peru for $2.9 billion.

- PowerChina’s purchase of Brazil’s Pontoon and its Ceará solar plant project for $360 million.

- Midea Group’s joint venture with Carrier in the Brazilian air conditioning manufacturing sector for $122 million.

Trends in Chinese infrastructure in LAC

New to the 2024 edition of the China-LAC Bulletin is the inclusion of Chinese firms’ participation in LAC infrastructure projects, using data from the Red Académica ALC-China’s annual “Monitor of Chinese Infrastructure to LAC.” These projects represent the sale of services from Chinese firms to LAC countries. They do not include projects where Chinese firms own the resulting projects (such as Peru’s new Chancay port, which is owned by Chinese infrastructure firm Cosco Shipping). Instead, infrastructure contracts have a paying client, usually the national government. In some cases, where the cost of the project is covered through a loan from the China Development Bank (CDB) or the Export-Import Bank of China (CHEXIM), the loans themselves are also included in the analysis of Chinese development finance in LAC, below.

The most notable trend in Chinese infrastructure projects in LAC is the rising importance of transportation infrastructure. As Figure 6 shows, this trend holds true in South America as well as Mexico, Central America and the Caribbean. Transportation projects have been particularly concentrated in rail infrastructure, including freight rail lines in Argentina and Brazil as well as urban passenger rail in Colombia and Mexico.

Figure 6: Chinese firms’ participation in LAC Infrastructure Contracts, by Sector

6A: South America

6B: Mexico, Central America and the Caribbean

In 2023, the largest Chinese infrastructure projects in LAC include:

- Metro lines and trains in Monterrey, Mexico, provided by China Railway Construction Corporation (CRCC) for $1.2 billion.

- The second stage of the Puerto Peñasco solar plant in Sonora, Mexico, provided by China Energy Engineering Group (CEEC) for $800 million.

- The Camaraçi Industrial Park in Bahia, Brazil, provided by BYD for $620 million.

- The Mesopotanian branch of the Urquiza railway in northern Argentina, provided by CRRC for $550 million.

Trends in Chinese development finance and debt in LAC

As shown in Figure 2, over the last several years, Chinese firms have opted to act as direct investors or contractors in LAC rather than relying on the intermediation of DFIs. The Chinese Loans to Latin America and the Caribbean (CLLAC) Database, maintained by the GDP Center and the Inter-American Dialogue, shows the resulting dramatic decline in DFI lending to LAC countries.

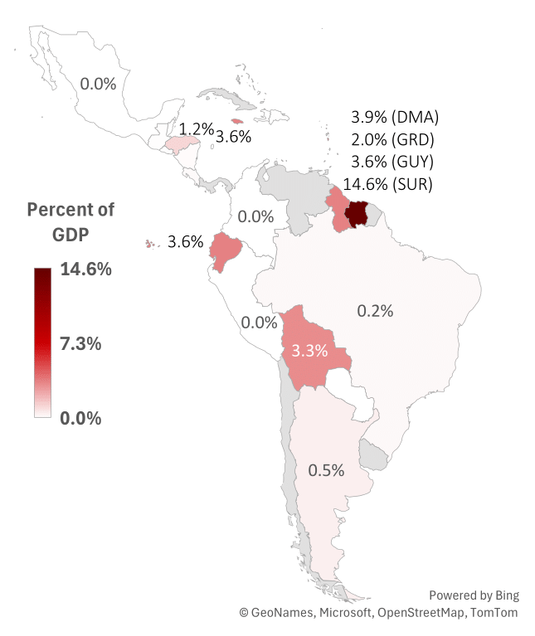

As DFI lending has declined, it is important to consider the remaining debt to China across LAC. Figure 7 shows LAC countries public and publicly guaranteed (PPG) debt to all Chinese creditors, as a share of each country’s GDP. Suriname stands out with much higher debt to China than any other LAC country, as it owes China 14.6 percent of its GDP. Five other countries owe China between 3 and 4 percent of GDP: Dominica (3.9 percent), Ecuador (3.6 percent), Guyana (3.6 percent), Jamaica (3.6 percent) and Bolivia (3.3 percent of GDP). No other regional country owes China more than 2 percent of GDP.

Figure 7: LAC Public and Publicly Guaranteed (PPG) Debt to China, 2022

The debt data in Figure 7 draws on the World Bank’s International Debt Statistics (IDS) database, which excludes higher-income countries such as Chile and Uruguay as well as countries without reliable public debt data such as Cuba and Venezuela. This omission is noteworthy, given the importance of Venezuela as a borrower from China. As the CLLAC Database shows, Venezuela alone has accounted for nearly half of total LAC borrowing from Chinese DFIs. However, it cannot be included in the China-LAC Bulletin’s debt analysis without reliable debt data.

Compared to other major categories of lenders, China is a relatively minor creditor in LAC, as Figure 8 shows. Figure 8 shows PPG debt levels to five categories of external lenders: bondholders, Chinese creditors, Paris Club creditors, multilateral development banks (MDBs) and other creditors. As Figure 8 shows, while China holds an important share of the total external PPG debt for multiple countries (especially Suriname), no LAC country – including Suriname – owes China more than these other categories. Thus, any meaningful debt restructuring will require the participation of all types of lenders.

Figure 8: LAC External PPG Debt by Creditor Category, 2022

Future prospects

The shift from strong Chinese sovereign finance to Chinese firms operating as direct investors and infrastructure providers likely signals a maturing of the China-LAC economic relationship. Firms are more willing to take on the challenges and risks of project design and implementation and no longer rely on Chinese DFIs for finance. This greater level of commitment and exposure amplifies the importance of cooperation for project governance to manage social, environmental and economic risks. These risks are likely to be quite different across the three major sectors whose rise has been highlighted: rail transportation infrastructure, transition minerals and agricultural products such as beef and soy. Each has a different implication for the region’s sustainable development.

Rail transportation – especially urban rail projects in Colombia and Mexico – can bring substantial benefits to reducing emissions and improving quality of life. Transition minerals’ sustainability depends heavily on the environmental and social protections applied to their production – a policy area still in development in LAC. For their parts, South American (and particularly Brazilian) beef and soy have long been linked to deforestation and environmental conflict with traditional communities with incomplete legal recognition of their land rights. However, Chinese importers have expressed interest in strengthening environmental governance for supply chains of soy in particular.

For these reasons, it is encouraging that LAC presidents have made dialogue with China a priority. Shared oversight of investor and supply chain performance will be key to ensuring that the China-LAC economic relationship is on a ‘win-win’ trajectory for all parties.

*

Read the BulletinNever miss an update: Subscribe to the Global China Initiative Newsletter.