Driving Change: The Role of African Host States in Shaping Chinese-Supported Power Projects

In the last 10 years, Chinese companies have significantly transformed Africa’s infrastructure, particularly in the energy sector.

However, when examining Africa-China engagement, research has predominantly focused on China’s influence, with limited attention given to the role of African host states in shaping project outcomes.

My new working paper with the Boston University Global Development Policy Center shifts this perspective, analyzing how host states can exercise agency to shape the outcomes of Chinese-supported power projects. This summary delves into the key findings and policy implications of this research.

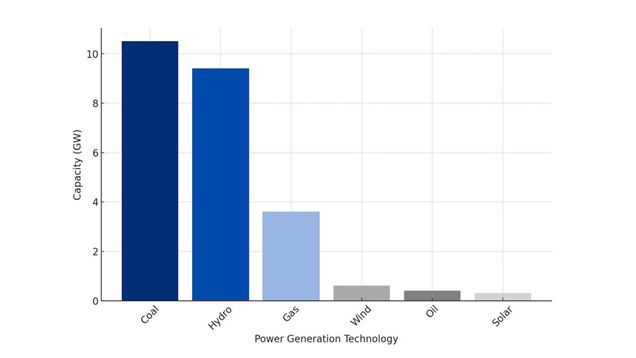

Africa is grappling with a severe power crisis, with over 40 percent of its population lacking access to electricity. The majority of Africa’s unelectrified population is in sub-Saharan Africa. Historically, African governments financed and constructed large-scale power generation plants, but fiscal constraints have driven the need for alternative investors in the sector. Chinese companies have helped fill this gap and significantly contributed to the power generation sector in sub-Saharan Africa, installing over 25 GW of generation capacity, as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Generation Mix of Chinese-Supported Power Projects in sub-Saharan Africa, 2000-2032

Notwithstanding these notable contributions, the outcomes of these projects vary widely across different countries. In my working paper, I investigate why these projects may vary by examining the financing and construction of hydropower plants by the Export-Import Bank of China (CHEXIM) and Sinohydro in Ghana and Uganda. The Bui hydropower plant in Ghana and the Karuma hydropower plant in Uganda were analyzed because despite the projects being relatively similar and being undertaken by the same Chinese actors, Ghana experienced more positive investment outcomes, with projects primarily built on time, at cost-competitive prices and meeting quality standards. In contrast, Uganda’s Chinese-supported projects faced delays, higher costs and multiple defects. The research identified several critical areas where both countries either exercised effective agency or fell short, significantly impacting their project outcomes. Key areas included policy and planning, brokering and negotiating, and project implementation and management.

Policy and Planning

Ghana showcased significant agency during the policy and planning phase of the Bui Hydropower Plant. The project was integrated into national development policy and energy sector planning, reflecting a longstanding government priority to address the nation’s energy needs. While Uganda’s policy framework prioritized hydropower development, it lacked a specific energy sector plan, which may have contributed to the challenges the Karuma Hydropower Plant faced.

Brokering and Negotiating

Both countries engaged in high-level brokering and negotiation for their projects. Ghana’s presidential delegation engaged Chinese leadership to secure financial support. China announced this support during the 2006 Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC). Uganda’s President Yoweri Museveni similarly engaged directly with Chinese leadership to secure funding during the 2013 BRICS Summit. However, Uganda’s presidential intervention bypassed an active competitive procurement process, leading to procedural controversies and impacting project outcomes.

Both countries attempted to negotiate better financial terms. Ghana succeeded in extending the commercial loan term, and Uganda succeeded in reducing the commercial loan interest rate. However, they were unsuccessful in other areas. Both countries could not negotiate an increase in the percentage of their concessional loans compared to their commercial loans.

Project Implementation and Management

Ghana ensured rigorous oversight and proactive management of the Bui Hydropower Plant, resulting in high-quality standards and timely completion with only minor delays. The hands-on technical team and support from the experienced owner’s engineer were crucial in maintaining project quality. In contrast, Uganda’s Karuma Hydropower Plant faced significant delays and quality issues due to insufficient supervision and management capacity at the beginning of the project. Initial oversight by the Ministry of Energy and Mineral Development (MEMD) was inadequate due to limited project management capacity and staffing, compounded by the appointment of an inexperienced engineering consulting firm as the owner’s engineer.

Policy recommendations

The comparative study of Ghana’s Bui Hydropower Plant and Uganda’s Karuma Hydropower Plant underscores the essential need for African governments to strengthen their skills and capabilities in planning for, developing and overseeing power generation infrastructure projects. The experiences of both countries offer valuable insights on strengthening negotiation skills, improving project management and monitoring, and utilizing experienced consultants.

To secure terms that benefit their countries while fulfilling investor needs, African governments should equip their officials with advanced negotiation skills and a thorough understanding of loan agreements utilized by Chinese investors. Alternatively, they may appoint advisors with the requisite loan documentation, negotiation and project monitoring and evaluations experience. This strategy, informed by the experiences of Ghana and Uganda, will maximize the host state’s ability to effectively negotiate to secure favorable financial conditions, ultimately impacting project costs.

African governments should develop a robust framework to oversee projects from inception to completion, incorporating active participation in the construction process. By investing in technical training for local engineers and staff, governments can more effectively supervise the work of their Engineering, Procurement and Construction (EPC) contractors. Establishing a reporting system to keep stakeholders informed about project progress, challenges and outcomes is also essential. Enhancing technical and managerial capacity within ministries and regulatory bodies will also lead to better oversight, effective management and adherence to high-quality standards, thereby mitigating the risks of suboptimal execution and delays. Governments should engage skilled consultants to provide technical guidance and oversight when in-house expertise is lacking. Hiring experienced owner’s engineers with a proven track record in similar projects is crucial for providing oversight and ensuring quality.

Finally, strengthening governance processes around the procurement of national infrastructure will limit political interference and ensure that the parties best qualified to implement the projects are appointed.

The development of hydropower plants in Ghana and Uganda highlights the significant role of host state agency in shaping project outcomes. As Africa continues to seek investment to grow its power sector, enhancing the skills, know-how and capacity of host states will be critical to ensuring successful power projects.

*

Read the Working PaperNever miss an update: Subscribe to the Global China Initiative Newsletter.