From Vicious to Virtuous: Understanding and Re-imagining the Relationships between Debt, Climate and Nature at COP16

By Rebecca Ray

Representatives from governments and civil society from around the world are gathering in Cali, Colombia this month for the 16th meeting of the Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity (COP16). They will take stock of progress and recommit to the goal of preserving global biodiversity through the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (KMGBF).

Four main high-level themes characterize COP16: implementing the KMGBF, pursuing peace with nature, financing biodiversity and the link between biodiversity and climate change. However, these four themes do not operate independently. Frequently throughout COP16, speakers have highlighted the ways that the global financial architecture can limit or enhance countries’ abilities to meet biodiversity and climate targets. Perhaps most visibly, the Expert Review on Debt, Nature and Climate – convened by the governments of Colombia, France, Germany and Kenya – launched its Interim Report on October 24, “Tackling the Vicious Cycle,” focusing on the ways that international financial reforms can better support developing countries’ sustainability agendas.

Simultaneously, a joint effort of several Latin American civil society groups released a series of reports on cyclical patterns of debt, extractive dependency, biodiversity loss and economic instability in the Amazon biome across five countries.

This synchronicity between policymakers and civil society shows a widespread agreement that negatively-reinforcing cycles have developed and must be replaced by new, more positive alternatives if the world is to meet its economic and environmental sustainability targets.

The connections between these opportunities – reforming the global approach to debt resolution, conserving biodiversity and mitigating and adapting to climate change – have been frequent themes of GDP Center research, including the Sovereign Debt and Environment Profiles Database and particularly the Debt Relief for a Green and Inclusive Recovery (DRGR) Project’s proposal, a joint initiative comprised of an international team of academics, policymakers and experts on sustainable development, in which GDP Center researchers participate.

The vicious cycle between economic instability, debt, biodiversity loss and climate vulnerability is challenging but not insurmountable. Understanding how the cycle can trap developing countries and limit their policy space is key in moving from vicious to virtuous, and forming newer, more sustainable and inclusive paths.

Business-as-usual: the vicious cycle

Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, currency market volatility and advanced economies’ interest rate hikes have raised borrowing costs for developing countries and made existing and new debts more expensive to repay. In 2024, sovereign debt service payments rose to an all-time high, squeezing the fiscal space and leaving the majority of economically vulnerable emerging market and developing economies (EMDEs) unable to invest in climate and development goals without facing insolvency.

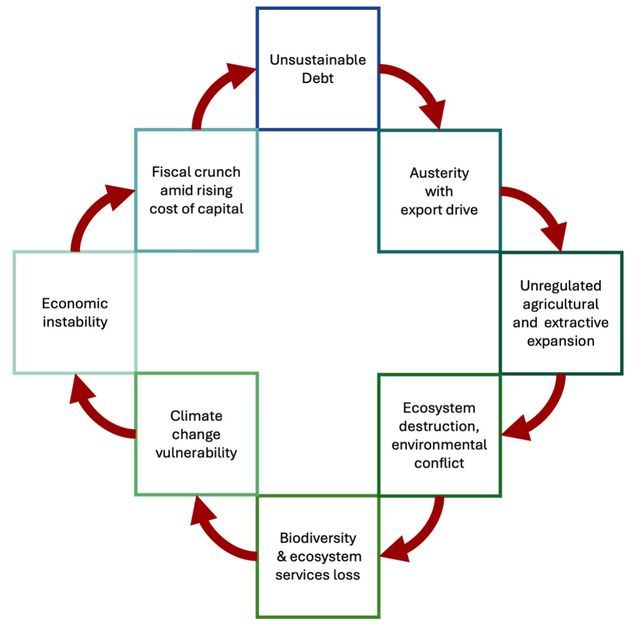

How that distressed debt is restructured can have significant impacts for EMDEs’ sustainability prospects. Figure 1 traces a ‘vicious cycle’ in which an austerity and commodity-export-focused debt resolution process deepens an EMDE’s dependence on unregulated and underregulated commodity production, damaging biodiversity, worsening climate vulnerability and economic fragility, and ultimately positioning them to need more borrowing in cases of extreme weather events.

Figure 1: A vicious cycle of debt, extraction, biodiversity loss and climate vulnerability

As Figure 1 illustrates, sovereign debt restructuring processes are accompanied by International Monetary Fund (IMF) agreements, which come with policy conditionalities aimed at enabling debt repayments, but which may cause other negative impacts. These typically include fiscal austerity measures – reducing government deficits or requiring government surpluses – often carried out through reducing government payrolls and eliminating public-sector jobs and investments. During these periods of debt resolution, governments face strong incentives – sometimes including direct conditions in IMF agreements – to boost exports in order to build up international currency reserves to ensure their ability to repay debts.

While exports are key to economic recovery prospects, developing countries’ traditional dependence on commodity production – paired with the high cost of capital during a debt restructuring – makes it likely that these export booms will be concentrated in natural resource-intensive agriculture and extraction sectors rather than industrial production. The combination of government austerity with a commodity export drive can prove a dangerous mix, resulting in reduced institutional capacity for regulating the natural resource sectors that traditionally comprise the majority of developing country exports. For example, recent research by UN Trade and Development (UNCTAD) estimates that 85 percent of least-developed countries are commodity-dependent, meaning that raw materials in the agricultural, mineral or energy sector comprise 60 percent or more of their exports. Thus, during a rapid export expansion, raw commodity producing, the expansion is likely to be concentrated in natural resource-intensive sectors rather than manufacturing sectors with greater value-added.

Reducing government oversight during an expansion push of natural resource sectors can create unregulated agricultural and extractive expansion into previously intact ecosystems, damaging forests and threatening Indigenous and other forest-dwelling communities. Ultimately such expansions risk ecosystem destruction and environmental conflict, as formal-sector productive frontiers move into forests and other crucial areas. In fact, new research by the Task Force on Climate, Development and the IMF finds that IMF program participation is associated with 9.2 percent additional average annual deforestation in the borrowing country.

The loss of intact ecosystems exacerbates climate change by destroying carbon sinks and can be devastating for Indigenous and other forest-dwelling and ecosystem-dependent communities. Less well-known are the commercial impacts of biodiversity and ecosystem services loss, often affecting the same commodity-based industries that took the place of intact ecosystems. Tropical forests serve as important regulators of rainfall patterns, meaning agro-industrial activities in associated areas are likely to suffer from reduced and less predictable rainfall patterns in the future. For example, as Brazil’s Amazon rainforest has had to contend with degradation and deforestation, it has also suffered from more frequent and severe droughts, threatening soy yields, reducing the level of the Amazon River to the point of impeding agricultural shipments for exports, and diminishing the output of hydropower dams.

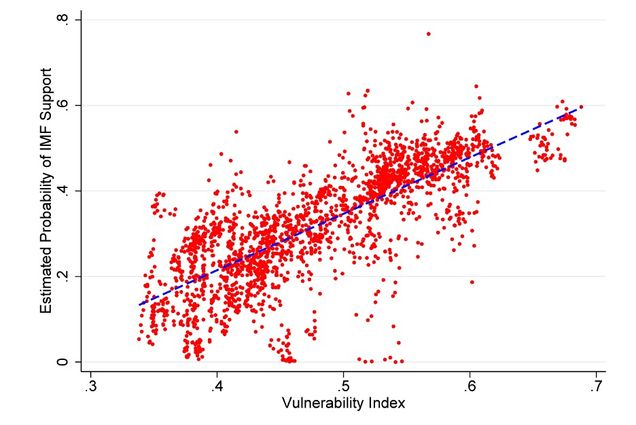

In essence, the loss of the ecosystem services – such as rainfall regulation, hydropower and transportation – is the opposite of climate change adaptation investment. As the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank recently noted in its recent report “Nature as Infrastructure,” ecosystems are a form of natural infrastructure, creating public goods that provide the basis for and protection of economic activity. Without these services, productive sectors face greater risks from climate change-linked extreme weather events such as droughts, floods and tropical storms. Entire economies’ climate change vulnerability rises, bringing economic instability and fragility and greater demand for IMF support, as Figure 2 illustrates.

Figure 2: Climate vulnerability and demand for IMF resources

In the increasingly frequent cases of extreme weather events, countries face an immediate reduction in fiscal space from increased demands for reconstruction and social supports as well as a reduced tax base from a damaged productive base. Furthermore, these risks are priced into bond ratings, so countries in this situation face a higher cost of capital to support these new fiscal demands. This combination makes debt stress more likely, as higher fiscal demands meet higher capital costs, leading to a return to the beginning of the cycle with unsustainable debt.

Business-as-possible: Positive alternatives

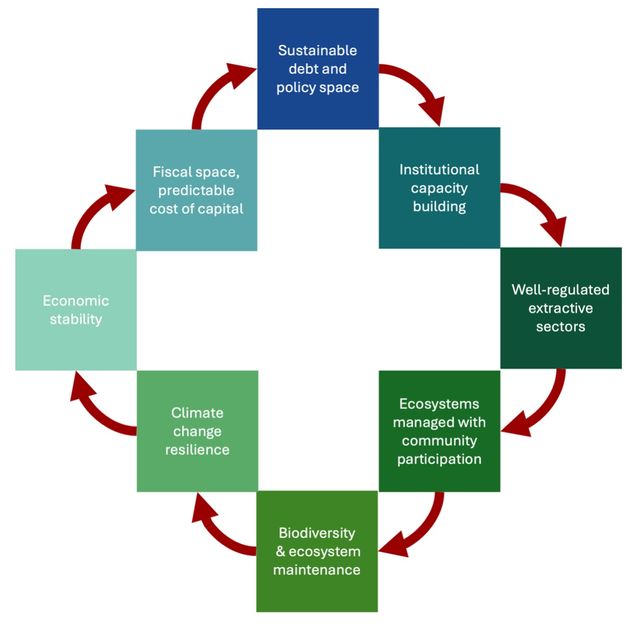

It is possible to work toward an alternative virtuous cycle, one built on increased institutional capacity, well-regulated agricultural and extractive sectors, forest-dwelling and ecosystem-dependent community participation, climate change resilience, and economic and fiscal stability. Figure 3 represents an alternative virtuous cycle.

Figure 3: Virtuous cycle of conservation, participation and effective regulation

Interrupting vicious cycles requires changing a key, early policy response. Indeed, the moment in the cycle most closely associated with triggering a vicious cycle is how debt is treated: whether to resolve unsustainable debt through a combination of fiscal austerity and commodity-led export growth, or perhaps through a positive alternative.

First, the IMF can play an important role in overseeing periods of debt restructuring. The IMF’s own research suggests that austerity provisions do not enhance growth prospects during times of crisis, and that therefore both the IMF and its member countries would be better served with a new approach, one less dependent on austerity measures, which may prove counter-productive. Furthermore, during IMF agreements, equipped with the knowledge that austerity during a commodity export boom is likely to bring environmental and social risks, the IMF can safeguard vulnerable communities and the ecosystems that provide their livelihoods by targeting these policy areas for protection. For example, from 2000-2020, less than one in 1,000 conditions targeted forest policy. Moreover, these instances were not universally supportive of conservation, but included instances of targeting reductions in regulatory requirements for exports of agricultural and forestry products. Protecting, rather than encouraging, the destruction of intact ecosystems is key for long-term economic growth with stability.

Secondly, the international community needs a more constructive debt resolution mechanism. A first step is to rely on an enhanced debt sustainability analysis that incorporates climate and development spending and risks. That way, it will be possible to more precisely assess the debt relief necessary to put countries on the path for growth and development. Moreover, it is key to ensure all creditors are included in restructuring and the intra-creditor competition does not lead to a race to the bottom where creditors end up with a very thin debt relief. To do so, creditors could adopt a “fair” comparability of treatment rule that would adjust debt relief to the ex-ante interest rate provided by creditors. For banks that issue loans on concessional terms – including MDBs and the Export-Import Bank of China – haircut levels would be quite modest, while commercial lenders and bondholders would be expected to make larger sacrifices, reflecting the fact that the risk of default was priced into the interest rates they originally charged. To deal specifically with commercial creditors’ claims, the DRGR Project’s proposal suggests a stick and carrots approach where creditors providing deep relief would swap old debt for newer sustainability-linked bonds that would come with a guarantee that shield creditors from a subsequent default episode. At the same time, it is important that legislation in countries with large bond markets, such as the United States and the United Kingdom, are suit to enforce the participation of private creditors in debt restructuring. Finally, for countries not facing debt distress, development financial institutions should provide more affordable finance as well as develop credit-enhancement mechanisms for private sustainable development finance, including guarantees and insurance programs. Figure 4 illustrates how these steps combine in the DRGR Project’s proposal.

Figure 4: Three Pillars for Debt Relief for a Green and Inclusive Recovery

Note: The ranges of the haircuts mentioned in the figure are in net present value terms.

Once sustainable fiscal and policy space has been maintained, other parts of the cycle can also be changed. Robust, consultation-based strategies for natural resource sectors and the regulations to oversee their production methods take time and resources to develop. For example, several years of civil society consultations formed an integral part of the creation of Chile’s “Energía 2050” energy transition strategy, including the strategy for developing the country’s lithium reserves. Processes such as this are capacity-building for policymakers, regulating ministries and the civil society groups that will eventually help provide accountability for performance, and can result in well-regulated extractive sectors.

As regulatory and strategic capacity expands, ecosystems managed with community participation can be planned and implemented. Community-based biodiversity management has also shown to be an effective tool for biodiversity conservation, with case study evidence emerging particularly in Asian and Latin American experiences. Other research shows that this approach benefits from additional time in planning stages to better mitigate specific local risks.

Such efforts take time, but by establishing successful biodiversity and ecosystem services maintenance, developing countries can prevent further vulnerability and build climate change resilience, reinforcing the foundation necessary for growth with economic stability, and preventing extreme weather events from eroding their fiscal space and cost of capital.

COP16: Envisioning a shift from vicious to virtuous cycles

The international financial architecture holds important sway over the dominant approaches to debt crises like the one currently unfolding across EMDEs. Choices made by major creditors and international organizations can limit or enhance policy and fiscal space for biodiversity and climate action and set the boundaries for global sustainability ambitions. Under a business-as-usual scenario, current patterns of debt renegotiation will continue to trap EMDEs in cycles of commodity dependency, climate vulnerability and economic instability.

However, global platforms such as COP16 enable cooperation among economic and environmental experts and can facilitate the development of more positive alternatives. The simultaneous release of two reports – one by the government-led Expert Group on Debt, Nature and Climate and the other by a coalition of Amazon basin civil society groups – shows widespread agreement that vicious cycles have developed and that the time is ripe to consider significant reforms to develop positive alternatives.

To grow beyond commodity dependence and safeguard biodiversity, developing countries need fiscal and policy space, and the confidence that this breathing room will remain long enough to support time-consuming but worthwhile consultation-based strategies and regulatory frameworks. Through significant reforms to the way sovereign debt crises are resolved, major creditors and international organizations can transform outcomes from vicious to virtuous cycles.

*

Never miss an update: Subscribe to the Global China Initiative Newsletter.