Lessons from the Past: The Impact of NAFTA on Mexico’s Export Specialization Pattern

With Chinese electric vehicle (EV) manufacturing giants like Jetour announcing plans to establish EV assembly plants in Mexico by the end of 2024, it is a critical time for Mexico to revisit its past success with the automotive industry. This can inform future decisions and help develop mutually beneficial strategies with respect to such investment deals with foreign private actors.

Mexico’s automotive assembly industry was established in the 1980s and was further bolstered by the signing of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) in 1994. In a new working paper, I assess the how the ratification of NAFTA influenced the composition of the Mexican exports’ basket by focusing on Mexico’s’ export specialization pattern into and out of certain products over time. Additionally, I look at how the accession of China to the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001 may have had a confounding effect on the potential export-led growth trajectory of Mexico.

Mexico’s history with NAFTA

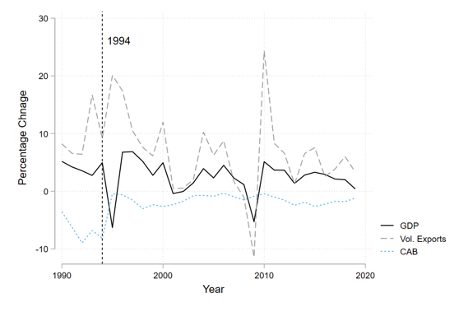

The Mexican government was motivated to sign NAFTA by the expectation that it would lead to the further expansion of trade and, thus, economic growth. However, Mexico’s gross domestic product (GDP) growth has been sluggish and hovering around 1 to 2 percent since the 2000s. As seen in Figure 1 below, there was a surge in export volumes following NAFTA’s implementation, though volumes steadily declined in the following years (with a notable exception in 2010, possibly driven by the US recovery following the 2008 financial crisis). Despite these lukewarm impacts on growth, a clear benefit of the agreement has been the stabilization of Mexico’s current account balance (CAB), which was erratic before NAFTA.

Figure 1: Selected Macroeconomic Indicators for Mexico

A closer look at Mexico’s exports since NAFTA

Mexico has been on a path of increasing export re-specialization since the early 1990s. Export re-specialization is characterized by the sequential shift in a country’s exporting pattern from diversification to specialization in more technology and capital-intensive products, typically at higher income levels. This phenomenon is unexpected for Mexico because is typically experienced by advanced economies, yet Mexico began to re-specialize in 1993 at a relatively low income level, and it appears to be permanent since the trend has continued for 26 years (from 1993 to 2019).

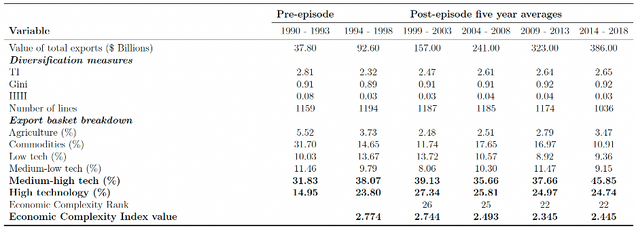

Looking at Mexico’s export basket technology intensity – or the level of technological sophistication required to produce the exported products – it is currently dominated by medium-high technology goods such as automobiles, chemicals and basic machinery. The shares of medium-high technology and high technology exports (such as aerospace, electronics and pharmaceuticals), seen in Table 1, increased immediately following re-specialization and NAFTA implementation. Since then, the share of medium-high technology goods has remained stable until the last interval of years when it increased to almost half of the export basket. At the same time, the share of high-technology goods increased until 2003 and then began to decrease.

Furthermore, the complexity level of the export basket – another measure of a country’s technological sophistication relative to other countries – has remained relatively stagnant and has even decreased in recent years compared to the 1994 – 1998 period. This may indicate that other countries are catching up to and even surpassing Mexico with more technologically complex exports. Therefore, understanding the agreement’s effects on export composition at the product level may also help explain the unexpectedly sluggish performance of the Mexican economy after NAFTA.

Table 1: Composition of Mexico’s export basket

Key findings

The agreement took a multifaceted approach to encouraging free and fair cross-border trade among the signatories (US, Mexico and Canada). To this end, it operationalized a 10-year phase-out of tariffs between the countries, removed investment-related barriers, and established intellectual property rights and environmental regulation rules – among other polices.

I primarily focus on the tariff elimination component of NAFTA. Since the US was, and still is, Mexico’s largest trading partner, I specifically examine the impacts of product-level tariff cuts on exports to determine whether Mexico specialized in products that benefited from the tariff reductions of the agreement. Furthermore, I analyze whether the product-level effects of the tariff cuts had a long-term impact on the export re-specialization trajectory of Mexico between 1994 and 2019.

The analysis indicates that the NAFTA tariff cuts contributed to export re-specialization, with the effects becoming evident mainly around five years after the signing of the agreement. Furthermore, the results of the export basket composition analysis show that the tariff cuts benefited low-domestic input-intensive semi-assembly industries, such as automobiles and electronics, while high-domestic input-intensive industries, such as food and beverages, chemicals and chemical products, lost their share of the export basket. Both high and medium technology intensive exports such as the automobile and electronics sectors, benefited from the NAFTA tariff cuts. However, at the time, Mexico’s participation in these industries was largely limited to semi-assembly activities. This is significant because even though the end product would be classified as a high or medium technology export, Mexico’s participation in the production of these products was mostly limited to labor intensive activities, and these were generally low value-added activities.

The results of the “China shock” analysis, which measures the product-level impact of China’s accession to the WTO, show that there was an overall negative short-term impact of about two years immediately after the shock on all Mexican export products. These impacts may not have been specific to Mexico since the accession of a major low cost-labor oriented competitor (i.e., China) to the WTO posed a threat to labor intensive export sectors of many developing countries in the short run. The short-run negative impact of the “China shock” is similar across industries with low- and high-domestic inputs. However, the results show that in the long run this shock negatively affected industries such as food and beverages, chemicals and chemical products.

In conclusion, NAFTA further facilitated export specialization in the growing semi-assembly low-labor cost-oriented industrial activity in Mexico. While this contributed to increased export income in the short run, specializing in these industries did not lead to technological upgrading within the Mexican economy. This is because Mexico did not produce the parts used in these industries locally but rather imported and assembled them. This means that there were minimal technological spillovers to the rest of the economy from these industries.

The frontrunner among these semi-assembly low-labor cost-oriented industries was the automotive industry. Mexico prematurely specialized in the automotive industry and did not focus on expanding other domestic input-intensive industries. In fact, domestic input-intensive industries were negatively affected following NAFTA, and the lack of domestic productivity upgrading may have contributed to Mexico’s inability to cope with the competition from Chinese products that entered the market in the following years.

Implications for Mexico’s trade future

Given that developing strong backward and forward linkages is essential for technological upgrading, improving domestic productivity, and ultimately, economic growth, this study underscores the importance of negotiating trade agreements and investment deals that benefit the growth of domestic input-intensive industries that may lead to technological upgrading along with those that rely on imported inputs.

Applying these lessons to the current EV-related investment climate in Mexico it is important for policymakers to have a comprehensive framework to attract investment deals with private actors that will not only benefit the Mexican economy in the short run but also lead to sustainable growth in the long run. Special attention should be paid to establishing backwards linkages with the Mexican economy where more domestic firms supply inputs to these companies. Additionally, attracting more manufacturing activity rather than assembly activities may also benefit Mexico through technology spillovers. In the long run, these conditions – such as having the local economy integrated into the EV supply chain and acquiring knowledge trough manufacturing spillovers – may aid Mexico in contributing to its new commitments to renewable energy.

Read the Working Paper*

Never miss an update: Subscribe to the Global Economic Governance Initiative Newsletter.