FAQs: The Chinese Loans to Africa Database

By Diego Morro

From 2000-2023, China’s development finance institutions (DFIs), the China Development Bank (CDB) and the Export-Import Bank of China (CHEXIM), and other Chinese commercial lenders provided approximately $182.3 billion in development finance to Africa, an amount comparable to the $209.5 billion committed to Africa by the World Bank from 2000-2022.

The Boston University Global Development Policy Center (GDP Center) provides open-sourced data products for researchers, policymakers, journalists and the public. Through its Data Analysis for Transparency and Accountability (D.A.T.A.) research group, the Global China Initiative (GCI) maintains and hosts a series of five databases tracking Chinese overseas lending and development finance projects to enhance transparency and facilitate research. The GDP Center views GCI database products as public goods and makes them accessible to those seeking insights into the trends and impacts of Chinese overseas financing activities.

GCI databases are global, regional and sectoral in scope. They include the Chinese Loans to Africa (CLA) Database, the China’s Overseas Development Finance (CODF) Database, the Chinese Loans to Latin America and the Caribbean (CLLAC) Database, the China’s Global Energy Finance (CGEF) Database and the China’s Global Power (CGP) Database. Each database’s methodology is explained in detail in the Database Methodology Guidebook, 2023. These five databases track international sovereign loans, also known as public and publicly guaranteed (PPG) loans, issued by Chinese financial entities. The CGP Database not only tracks PPG lending but also China’s foreign direct investment (FDI) into overseas power plant projects.

This blogpost provides answers to frequently asked questions regarding the scope, methodology and distinguishing features of the Chinese Loans to Africa Database.

What does the Chinese Loans to Africa (CLA) Database track?

While all five databases track PPG loans, the CLA Database covers a broader scope of lenders than the other four GCI databases. The database tracks lending from both Chinese DFIs as well as other lenders such as commercial banks or companies. DFIs are independent public institutions with policy mandates for supporting development. They deploy project-specific loans and other financial instruments under a government-led strategy. In contrast, Chinese commercial banks and Chinese companies do not have explicit mandates to support development. The CLA Database also tracks syndicated loans (loans made by a ‘club’ of lenders), where the specific amount committed by Chinese lenders can be parsed.

What is PPG lending and why does CLA track it?

The World Bank defines PPG debt as the external obligations of public debtors that are comprised of two components:

- Public debt, which is borrowing by the national government or agency, by a political subdivision or agency, or by autonomous public bodies that are majority government-owned.

- Publicly guaranteed debt, which is borrowing by a minority government-owned body or private agency that is guaranteed for repayment by a public entity.

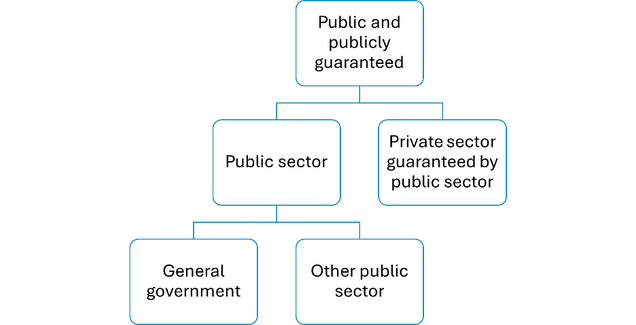

Figure 1 shows the components of PPG debt by debtor.

Figure 1: Public and Publicly Guaranteed Debt (PPG) Classification

GCI relies on the World Bank debtor reporting manual for determining whether a loan qualifies as PPG lending. It considers a recipient entity with more than 50 percent government ownership, including state-owned enterprises, a sovereign borrower. In cases where there is 50 percent or less government ownership, the entity must have a sovereign (government) guarantee for the loan to qualify.

Analyzing PPG lending captures an accurate picture of Chinese overseas development finance. Public lending involves an explicit repayment obligation. Publicly guaranteed debt, on the other hand, is the debt of a private person or enterprise whose repayment service is guaranteed by a public body. By studying PPG loans, researchers can understand the full extent of a recipient government’s financial responsibilities towards other countries and study its effects on sustainable development. This methodology also allows for direct comparisons with sovereign loan data from the World Bank International Bank for Reconstruction and Development and International Development Association as well as other global creditors whose commitments are included in the World Bank International Debt Statistics database. This standard of comparison is apt for evaluating development impacts of Chinese lending and comparing it with other DFI financing.

Lending to the private sector, which includes all other non-guaranteed debt of the private sector, is beyond the scope of GCI databases, as it does not result in sovereign debt. For instance, loans that are issued to joint ventures majority-owned by Chinese companies in African countries that are not otherwise guaranteed by the host government, do not appear in a recipient country’s balance sheet as public debt and do not involve a repayment obligation by the state recipient.

What time period does CLA cover and why?

The CLA dataset begins in 2000 following the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) Initiative, which reset the external debt profiles of many African countries and reduced their debt burdens. By capturing data since 2000, the CLA Database provides insights into how sovereign debt has evolved in the new millennium. The focus on the post-2000 era is particularly suitable given China’s increasing engagement in Africa, especially through initiatives like the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC), also launched in 2000.

Who are some of the common non-DFI lenders in the CLA Database?

Apart from DFIs, the CLA Database covers commercial lenders including state-owned banks and Chinese state-owned enterprises and companies. The 2024 update to the CLA Database shows that commercial lenders represent 16 percent of the total value of loan commitments to Africa, compared to 83 percent for DFIs. Most of the non-DFI lending comes from China’s four major state-owned banks, including Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC), China Construction Bank (CCB), Bank of China (BOC) and Agricultural Bank of China (ABC). The People’s Bank of China (PBOC) features in the CLA Database with two loan commitments, reflecting the limited direct involvement of China’s central bank in overseas lending, which is primarily handled by China’s DFIs and commercial lenders.

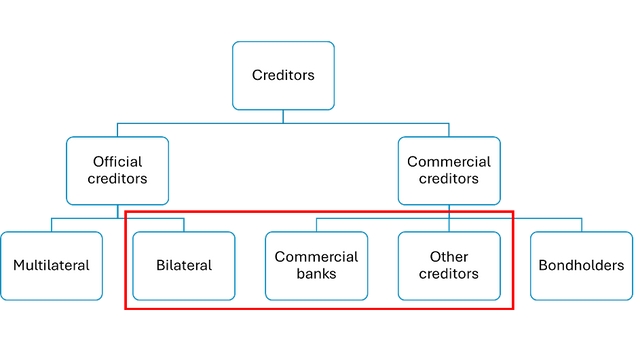

The other major category of non-DFI lenders is Chinese companies, who may offer goods or services on credit to African governments. These tend to be large state-owned companies including Sinohydro, Aviation Industry Corporation of China and others. Finally, a Chinese government agency that is not a DFI but that also provides loans is the China International Development Cooperation Agency (CIDCA). CIDCA administers zero-interest loans (ZILs), often paired with grants under economic cooperation agreements, for projects in recipient countries. Figure 2 shows debt by different creditors and highlights in red, the types of official and commercial lenders that are covered by the CLA Database.

Figure 2: Debt by Creditor Type

How does the CLA Database compare to other databases tracking Chinese loans to Africa?

The CLA Database tracks PPG loan commitments from Chinese lenders by closely following the World Bank methodology on international debt statistics. This enables direct comparison of China’s overseas finance with that of other countries and multilateral banks, such as the World Bank. Databases elsewhere may track loan commitments to private entities within a recipient country where that government would not have repayment liability.

In terms of financial instruments, the CLA Database focuses on loans and does not track grants, scholarships, currency swaps, debt relief or investments. Grants or scholarships fall in the category of aid that does not have to be repaid, which falls outside the scope of the transactions and projects tracked.

Currency swaps (mostly carried out by the People’s Bank of China) are excluded, as they represent rights to draw money, which is distinct from a loan that becomes debt. (These instruments are typically short-term operations with a duration of 24 hours to 24 months.) Currency swaps are however included in the Global Financial Safety Net (GFSN) Tracker. Generally, the GFSN is a set of institutions and financial instruments that countries can access to manage or mitigate short-term balance of payments and currency market stress. The GFSN Tracker covers international reserves, bilateral swap agreements, regional financial arrangements and loan agreements with the International Monetary Fund (IMF). Loans are included regardless of the original currency denomination.

How can I learn more about the CLA Database methodology?

The GDP Center regularly updates its Database Methodology Guidebook, which outlines the methodology and parameters used by researchers to construct the CLA Database and the other four databases tracking Chinese overseas finance and associated projects.

Feedback or questions? Reach out to Diego Morro, Data Analyst and Database Manager, dm3760@bu.edu.

*

Never miss an update: Subscribe to the Global China Initiative Newsletter.