Political Coalitions for the Energy Transition? How Foreign Companies are Shaping Renewable Energy Policymaking in the Global South

By Ishana Ratan

Low- and middle-income countries face the dual goals of decarbonization and development.

It might be expected that among these countries, those with a higher share of foreign direct investment (FDI) in renewable energy will lead in the energy transition. In renewable energy, foreign companies can bring skills, technology and capital to markets that lack such resources themselves, while domestic firms must learn how to install solar from scratch. As a result of these economic advantages, foreign firms are well-positioned to drive quick renewable energy scale-up.

However, in a new working paper published by the Boston University Global Development Policy Center, I find that low- and middle-income countries reliant on foreign investment experience slowdown in solar industry growth after initial fast-paced scale-up, while those with more domestic firms have a slower, but steadier, pace of growth. The paper argues that this pattern comes from foreign companies’ reaction to regulatory challenges in renewable energy. Namely, in the face of regulatory hurdles, foreign firms tend to exit markets while domestic firms will lobby for policy improvements. While foreign firms can build large-scale solar projects more quickly than domestic firms, as regulatory updates need to be made, these firms are less likely to work with policymakers towards policy reform. As a result, foreign investment leads to solar scale up in the short term, but stagnation in the long term.

The case of Colombia illustrates the potential pitfalls of reliance on foreign companies for renewable energy investment. In 2019, Colombia was poised to scale up solar quickly through foreign investment, with over six gigawatts (GW) of permits – a significant addition to their 17 GW of existing energy capacity – issued for renewable energy. However, by 2024, the tables had turned for the energy transition. Facing regulatory hurdles in grid connection and land acquisition, foreign companies from France, Norway and China are all leaving the country rather than working with regulators to update renewable energy policy. Now, Colombia faces a looming energy crisis as drought threatens its primary source of electricity – hydropower – while renewable energy projects remain in limbo.

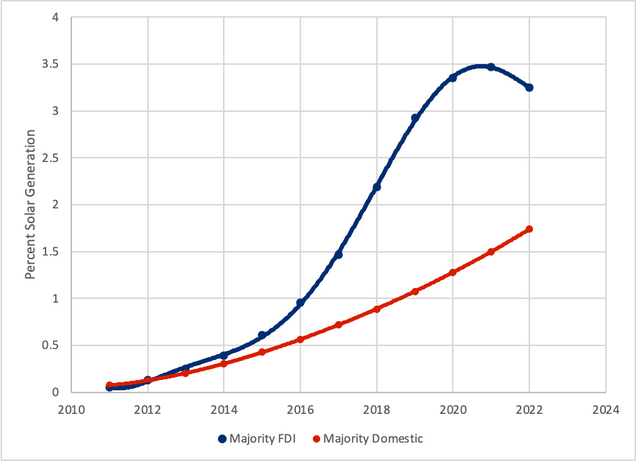

Colombia is one case in a broader pattern of foreign renewable energy investment rise and fall, and many countries with high shares of foreign investment in renewable energy follow this pattern. Vietnam, for example, is another notable case where renewable energy grid challenges sent foreign companies running for the hills. Figure 1 illustrates divergent patterns in solar investment among countries with more foreign investment (blue) versus more domestic investment (red). Countries reliant on FDI scale up quickly but have stalled, while those with more domestic investment grow slowly but steadily.

Figure 1: Solar Generation and Investor Ownership

The study examines how the ownership of solar investments affects long-term policy improvements in renewable energy. Using a unique dataset on solar projects and over 100 interviews with firms and policymakers across the three cases, Colombia, Malaysia and Panama, I find that while foreign investors can spur rapid solar growth, they often abandon projects when faced with regulatory hurdles. In contrast, domestic firms — which are more embedded with local networks — are more likely to work with policymakers through these challenges, drive the adoption of policy improvements and slowly but steadily advance solar energy in the Global South.

Foreign investment drives rapid growth — but with a catch

The study identifies three key findings to inform policy for the energy transition.

The first is that FDI enables quick renewable energy scale-up in the short term but stagnates in the long term. Large multinational firms, leveraging experience from their home countries, typically lead initial waves of solar projects, bringing substantial capital and expertise. For example, in 2019, foreign firms from Spain, Portugal and Italy flocked to Colombia after their home countries phased out subsidies, leading to significant optimism around the expansion of Colombia’s solar capacity.

Unfortunately, this fast-tracked growth is often fleeting. When foreign firms face regulatory challenges — such as delays in permits or onerous bureaucratic hoops — they tend to exit the market. The study identifies a common pattern among FDI-reliant countries: foreign firms bring rapid initial growth but leave when complications arise. In Colombia, bottlenecks with grid permits and challenges in land management have pushed many foreign firms to abandon their projects rather than work with local bureaucrats to solve issues.

Domestic firms are key to long-term stability

The findings suggest that domestic firms are consistent advocates for policy reform. Unlike foreign firms, domestic companies tend to lobby regulators for policy reforms when faced with local regulatory challenges. Interviews conducted for this paper reveal that domestic firms are often better positioned to lobby for reforms, using their embeddedness in social and political networks to advocate for change. Because solar energy policymaking is decentralized across local institutions, embeddedness is crucial to effectively lobby policymakers for reform, and allows even small domestic firms to exercise “outsized” influence over policy adoption.

The paper uses the case of Malaysia, which restricted solar investment to domestic firms in the first few years of policy adoption, to trace how domestic firms work with bureaucrats to improve policy. In Malaysia, domestic solar firms went from being viewed as “tree huggers,” per one solar industry expert, to providing regulators with pro-solar policy recommendations in the face of grid operator opposition to renewables. Per a bureaucrat at the Ministry of Energy and Water, new policy updates to solar energy market structure are due to consistent advocacy from the solar industry association. These interviews show that domestic firms, by remaining in the market and actively pushing for regulatory improvements in the face of opposition, can help sustain the energy transition in the long run.

Collaborative policies could amplify growth

The divergent behavior of foreign and domestic firms in renewable energy suggests a need for policy that bridges their strengths. I argue that while FDI can provide quick growth in the early stages of renewable energy investment, the embeddedness of domestic firms is crucial for regulatory reforms that promote investment in the infrastructure, technology and market models necessary for energy transition. Government policies that encourage collaboration between foreign and domestic firms could offer a way forward. By encouraging partnerships, low- and middle-income countries could enable foreign firms to navigate the regulatory landscape more effectively, while domestic firms benefit from the capital and expertise of foreign investors.

There will be challenges; at first, domestic firms often lack the skills necessary to collaborate with foreign firms on large-scale solar projects. Collaborative measures, as well as domestic capacity building, will both be necessary to encourage regulatory reforms and smooth the path for future solar investment.

Conclusion

The working paper offers vital insights for low- and middle-income countries that are balancing the need for quick renewable energy scale up in the short-term and long-term decarbonization. The findings suggest that while foreign investment drives rapid growth, it is embedded domestic firms that provide the bedrock of long-term policy reform. To avoid the rapid rise and fall that often plagues FDI-led solar investment, Colombia and similar countries may benefit from policies that foster collaboration, encourage local capacity-building and streamline regulatory frameworks.

As the Global South navigates the demands of energy transition, countries will face both the opportunities and challenges presented by different investors. In recognizing the complementary roles of both domestic and foreign firms, countries can lay the groundwork for a resilient renewable energy future.

Read the Working Paper*

Never miss an update: Subscribe to the Global China Initiative Newsletter.