Seminar Summary – Disease, Disparities, and Development: Evidence from Chagas Disease Control in Brazil

On November 20, 2024, the Human Capital Initiative (HCI) hosted Jon Denton-Schneider, Assistant Professor of Economics at Clark University, for the final installment of the 2024 Fall HCI Research Seminar Series. He presented his joint work with Eduardo Montero at the University of Chicago titled, “Disease, Disparities, and Development: Evidence from Chagas Disease Control in Brazil.” Denton-Schneider’s work explored the impacts of Neglected Tropical Disease (NTD) control on reducing racial and socioeconomic disparities in health outcomes in Latin America.

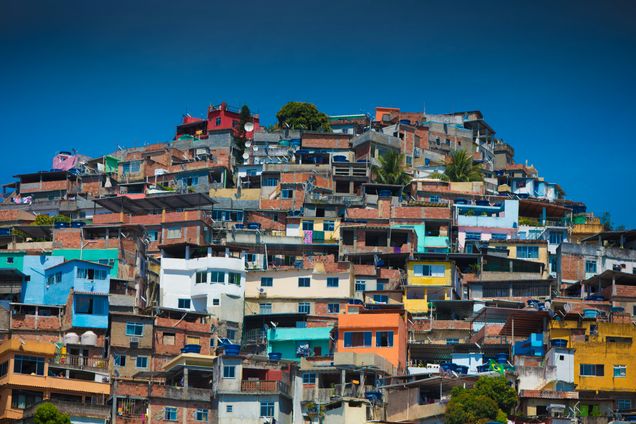

Denton-Schneider began his presentation by giving an overview of Latin America’s current standing with Chagas disease, which is unique to the region. Latin America is already one of the world’s most unequal regions, both in terms of race and socioeconomic inequality. Chagas primarily occurs among poor, non-white and rural Latin Americans, and has a very high morbidity rate. It is described as a “silent killer,” as the disease’s non-specific cardiovascular symptoms appear over a long (10-plus year) period. Denton-Schneider alluded that Chagas could potentially be responsible for some of the disparities and underdevelopment in the region, and tackling the burden of NTDs in Latin American countries more broadly could be one way to address these disparities in health and development.

Denton-Schneider and Montero’s research addressed two key questions: Does NTD control reduce disparities and underdevelopment? And are there other effects beyond individuals’ labor market returns? The authors set about answering these questions through analyses of a historic 1980s spraying campaign in Brazil to reduce Chagas vectors. Their methodology included multiple difference-in-difference analyses to understand the effects of this program on individuals, municipalities and the Brazilian public health care system. Chagas can lead to cardiovascular stress and heart problems, which are very expensive healthcare services and cause strain on Brazil’s universal health system. They also included a cost-benefit analysis and considered the potential broader effects of expanding this spraying campaign across Latin America. Their work feeds into a larger scholarly conversation surrounding NTDs and development as well as the relationship between health, inequality and intergenerational cycles of poverty.

The authors found that non-white adults growing up unexposed to Chagas (the generation following the Chagas eradication campaign) had a 2 to 4 percentage point increase in income distribution, with no effect for white adults. They also reported that literacy rates increased by 0.5 percentage points for non-white women growing up without Chagas exposure, with no effect for men or white adults. Years of schooling trended in a similar direction for non-white women, however with a very small effect size. Denton-Schneider hypothesized that this was because the marginal benefits of women dropping out of school and working were less than their male counterparts due to differences in skills and work opportunities; this could also generally be explained by parental preferences. Formal employment for non-white adults increased by 2 to 5 percentage points, with no effect for white adults. This was consistent with income patterns, and Denton-Schneider explained that this was logical given that healthier adults can engage in employment at higher rates. On a more macro scale, gross domestic product (GDP) per capita increased by 10 percent over 30 years, aggregated across municipalities. In terms of the public healthcare system in Brazil, the authors observed that there was a 19 percent decrease in hospitalizations and a 16 percent decrease in spending following the intervention. Denton-Schneider found a 16 percent Internal Rate of Return from the cost-benefit analysis.

The audience had many salient questions throughout the presentation. There was a recurring discussion about the cycle of Chagas disease and poverty, and whether Chagas could be thought of as a symptom of poverty rather than its cause. Another participant was curious as to why the Chagas intervention addressed vector control instead of larger symptoms of poverty. Denton-Schneider responded that disease and poverty effects are in fact multidirectional, and poverty can impact the burden and spread of disease. He noted that using a disease-side intervention was much cheaper than a poverty-alleviating program, such as building new housing or creating job opportunities. Additionally, once houses are treated for Chagas vectors, the bugs will not return, making the intervention an effective long-term solution. Another participant was curious about the mechanisms contributing to the increase in GDP per capita, to which Denton-Schneider answered that more qualitative research would be needed to understand the impacts of disease eradication on social conditions and population economic outcomes.

Denton-Schneider and Montero’s research adds to the growing body of literature exploring how disease treatment and control can impact broader issues such as poverty, employment and education. As climate change leads to rising temperatures in various regions, there is a risk that Chagas disease could spread, making more areas of the United States conducive to the proliferation of its vectors. The positive effects of this intervention on racial and socioeconomic disparities offer hope that further healthcare research can tackle not only health issues but also the broader social determinants of health.

*

Never miss an update: Subscribe to the Human Capital Initiative newsletter.