The IMF’s 17th General Review of Quotas Needs a New Formula to Deliver on Development

By Tim Hirschel-Burns and Marina Zucker-Marques

Quotas are at the core of the International Monetary Fund (IMF)’s finances and governance, and they are overdue for reform. Quotas are the primary funding source to support the IMF’s lending and operations, and they determine the amount countries can borrow from the IMF, their share of Special Drawing Rights (SDR) distributions and IMF members’ voting rights.

The IMF’s Articles of Agreement require that every five years the institution undertakes a process called the General Review of Quotas to ensure the level of quotas is adequate and the distribution reflect members’ relative positions in the global economy. During the last round, completed in late 2023, the 16th General Review of Quotas (GRQ) ultimately concluded with no realignment, resulting only in an equiproportional increase that essentially increased IMF firepower while keeping the distribution of quotas between members unchanged. The last realignment in IMF quotas was over 15 years ago, in 2010 with the 14th GRQ. As a result, quotas are out of step with today’s economy: emerging market and development economies (EMDEs) including China account for 60 percent of global gross domestic product (GDP) but hold just 40 percent of IMF voting power. The Fund’s current distribution of quotas threatens its legitimacy.

A failure to achieve real realignment in the 17th GRQ, which is set to end in 2028, would constitute an enormous blow to the IMF’s credibility. The Group of 24 (G-24) said that the last review’s failure to produce realignment “undermine[s] the organization’s legitimacy and credibility,” while the International Monetary and Financial Committee (IMFC) has acknowledged “the urgency and importance of realignment in quota shares.” In recognition of this urgency, the IMF Board of Governors set a June 2025 deadline to make progress on possible approaches to quota realignment, including a new formula.

A new report from the Boston University Global Development Policy Center explores ways to better align the 17th GRQ with the growing economic weight of EMDEs, while also increasing their voice and representation in IMF governance. It finds that the current IMF quota formula is inadequate for enhancing the voice of EMDEs as a group, jeopardizes the voice of the poorest members and is politically unfeasible. Full alignment with the existing formula would undermine the US veto and nearly grant veto power to China.

As a solution, the report recommends adopting a new and simplified quota formula. It also highlights that increasing IMF basic votes would strengthen the voice of EMDEs but notes that this measure alone would not address China’s underrepresentation, requiring complementary policies. Lastly, the report advocates for broader governance reforms to enhance the voice of EMDEs and address concerns about the IMF’s legitimacy.

The current formula is flawed

The current IMF quota formula, approved by the IMF membership, including the veto-holding US, is as follows:

CQS = (0.5 GDPblended + 0.3 Openness + 0.15 Variability + 0.05 Reserves)Compression Factor

In a nutshell, the formula can be explained as:

- GDP: The 3-year average of GDP. Using 60 percent GDP at market prices (MER) and 40 percent GDP at purchasing power parity (PPP).

- Openness: The 5-year annual average of the sum of current receipts and current payments of all economic transactions between resident and nonresident entities other than those relating to financial account transactions.

- Variability: The variability of current receipts and net capital flows measured as the standard deviation from a centered 3-year trend over a 13-year period of the sum of current receipts and net capital flows or minus the financial account balance.

- Reserves: The 12-month average of official reserves of the last year included in the data.

- Compression factor (k): This exponent (currently k=0.95) aims to reduce quota share dispersion by reducing shares of larger members and increasing those of smaller ones.

This paper defines political feasibility as requiring the maintenance of the veto power of incumbent groups (the US and Euro Area) and preventing their perceived contenders (like China) from gaining veto power – as veto-holders could veto the reform. Under these terms, the current formula is not the best guidance for current realignment.

Typically, the quota formula applies to newly created quotas, not redistributing existing ones, but if the entire quota distribution were realigned strictly following the current IMF formula:

- US voting power would drop to 13.99 percent, causing it to fall below 15 percent and lose its veto at the IMF.

- China’s voting share would more than double from 6.08 percent to 13.84 percent and almost surpass the US because China’s economy has grown so significantly since the last quota realignment.

- Emerging market and developing regions outside of Asia would lose voting power, rather than increase, with many of the poorest IMF members facing a reduction in quotas.

A way forward

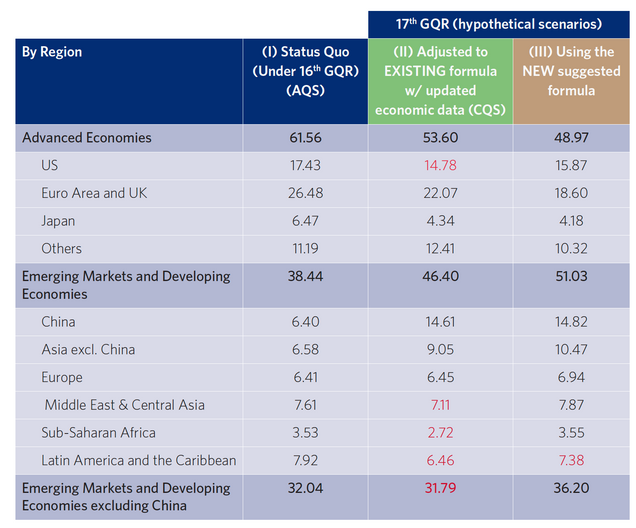

The paper analyzes a range of scenarios and finds that there are alternate formulas that could increase EMDEs’ quotas as a group while remaining politically feasible. As shown in Table 1 below, the suggested new formula would keep the US above the 15 percent veto threshold, keep China below 15 percent and increase quotas for EMDEs other than China.

CQS = (0.85 GDPblended + 0.15 Variability)0.903Compression Factor

The formula above is simplified, consisting of just two variables: GDP with an 85 percent weight (a blend of 55 percent MER rates and 45 percent PPP rates) and Variability with a 15 percent weight. The compression factor would be 0.903, an important change for EMDE representation because increasing the weight of the compression factor serves to increase quotas for small economies. Unlike the current formula, EMDEs other than China would increase their quotas, growing from 32.04 percent of all quotas to 36.2 percent. China would still experience a significant increase in its quota, and this is a natural consequence of the growth in China’s economy—every scenario analyzed would produce a major increase for China.

Table 1: Quota Shares Under the Status Quo and Different Scenarios

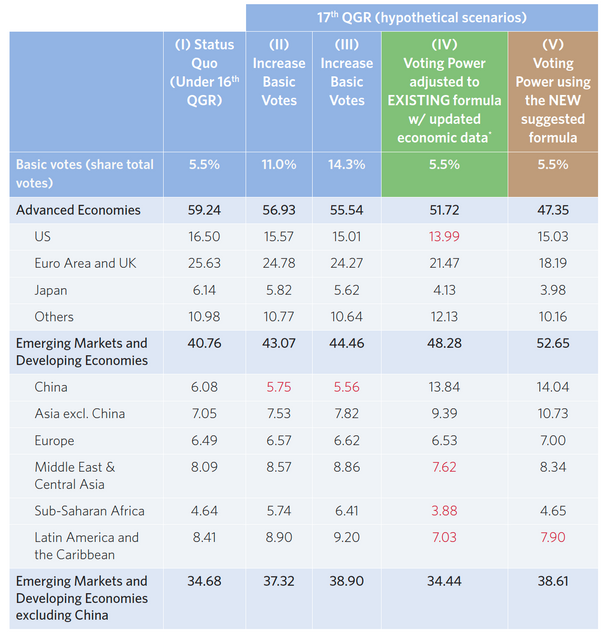

Basic votes also have an important role to play. They are granted equally to all countries, making them particularly advantageous to small economies. An increase in basic votes would create losses for large quota holders, but those losses would be relatively evenly distributed between them. Table 2 below shows the effect of increasing basic votes from the current level of 5.5 percent to 11 percent—the level at the time of the IMF’s founding—or 14.3 percent, the maximum increase that would not erode the US veto. While such increases in basic votes without a formula-based quota increase could increase the representation of EMDEs other than China, it would lead to a decrease in China’s quota. Given how significantly China’s quota lags behind its position in the world economy, addressing China’s concerns would require complementary measures. For instance, the 17th GRQ could increase basic votes with an ad hoc quota increase for China.

Table 2: Summary: Voting Power Under the Status Quo and Under Different Reform Scenarios

Source: Colodenco et al. 2025.

In the end, a politically acceptable quota realignment will likely require a package of reforms. An anti-dilution measure could help protect the quotas of individual EMDEs that would lose out in a new formula. Broader governance reforms outside the formula and basic votes can also expand voice for EMDEs and compensate countries that do not gain voice in the quota increase. These measures include increasing the number of Executive Board chairs for EMDEs, reducing the over-representation of Europe in the Executive Board and reconsidering the composition of some chairs. Other measures include ending the “Gentleman’s Agreement” where a European is de facto chosen to be IMF Managing Director and pursuing the more politically ambitious reform of separating quotas’ role in voting from the other uses of quotas, such as borrowing limits or SDR allocations. EMDEs can use venues like the United Nations and the Group of 20 (G20) to advance these reforms.

The combination of the preferences of current veto holders, the enormous growth in the Chinese economy and stagnant growth in many EMDEs creates a very challenging context for quota realignment. However, after two consecutive quota reviews without any realignment, the IMF cannot delay any more if it is to remain relevant and effective in the global economy. A fair outcome at the 17th GRQ is an imperative for developing countries. Fortunately, there are available options that would both achieve meaningful realignment and not cross political red lines, and IMF members must take them.

Read the Report*

Never miss an update: Subscribe to the Global Economic Governance Newsletter.