All Talk, Little Action: Between the Lines of ‘Whatever it Takes’ at the IMF and World Bank Annual Meetings

After many months of unprecedented interventions from governments around the world to save lives, the primary focus at the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank Annual Meetings last week was on responding to the economic crisis triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic.

While the rhetoric from the IMF and World Bank pressed the need for a just and green transition to respond to the pandemic and build a more resilient future, the evidence so far shows that these powerful institutions and wealthy countries are not yet delivering the intervention the moment requires. What is more, if these institutions continue to under-resource the global response and ignore the cracks that predate the pandemic, they risk deepening the crisis for years to come. According to the United Nation Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) Trade and Development Report (TDR) released last month, without a systemic approach to the pandemic that can tackle the many pre-existing conditions that affect our international economic frameworks, a resilient, more equal and environmentally sustainable world will be out of reach.

What is set to be the worst global recession since the 1930s will translate into unprecedented hardship for regular people without ambitious policy intervention: the International Labour Organization estimates almost 500 million jobs have already been put in jeopardy and the World Bank has estimated 150 million more people will be in extreme poverty by 2021. These impacts are not equally distributed, falling hardest on those already marginalized, such as women, informal workers and migrants.

While wealthy G20 countries have been able to spend around $13 trillion in measures to protect their citizens and tackle the spread of the virus, many countries in the Global South simply don’t have access to this sort of resource. Earlier in the pandemic, UNCTAD and the IMF estimated that Emerging Market and Developing Countries (EMDEs) needed $2.5 trillion to mount similar protections for their own citizens, but Global Development Policy Center (GDP Center) research has found that the Global Financial Safety Net (GFSN) has so far been unable to release the liquidity EDMEs need to meet their needs. Despite this, the G20 did not reach a consensus on a broader issuance or reallocation of Special Drawing Rights (SDRs) in their communique, which would have been one of few levers available to access more resource and has been broadly backed by civil society including the G30.

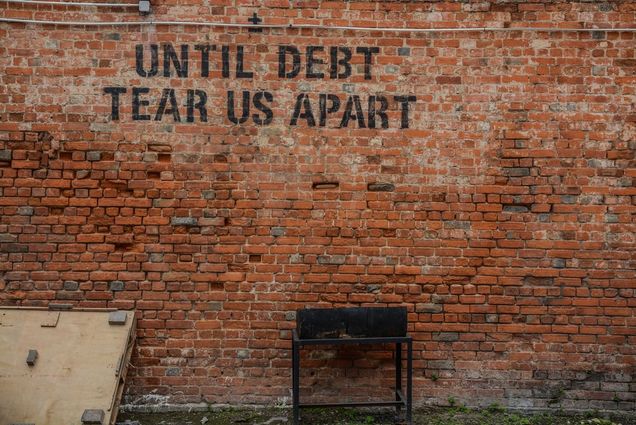

In her opening speech, Kristalina Georgieva, the Managing Director of the IMF, noted how important it was to provide adequate support to ensure EMDEs can respond to the pandemic’s pressures, stating that “we are only as strong as the weakest climbers.” What is not surfaced in this metaphor, however, are the structural challenges which ensure EMDEs remain weak in the first place. The clamp on fiscal space in the Global South – a rising debt burden, unprecedented capital outflows, the collapse of global supply chains, the drain of illicit financial flows on the public purse, and health systems deprived of public funds – were all risks prior to the pandemic, and identified as such by the G24 communique to the Annuals. So, while Georgieva is right to push the international community to step up to the funding needs, leaving these structural challenges intact would amount to applying a bandage, while the diagnosis is chronic.

Amidst powerful speeches of solidarity and renewed multilateralism, this sort of systemic approach continues to evade decision-makers in the detail. While the IMF’s debt write-offs in April and the extension of the Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI) agreed by the G20 last week have alleviated the immediate debt pressures for some countries, it falls far short of the trillion dollar write-off UNCTAD has estimated will be needed to evade economic disaster. Further cooperation on extending the DSSI is a welcome step, but the lack of participation from the private sector means developing countries continue to service private debt, while public health systems are left under-resourced and struggling to protect lives. At the same time, many countries have chosen not to participate because of the risk of downgrades from Credit Rating Agencies (CRAs), which will impact future access to finance and further hamper fiscal space. While it is progress to hear the World Bank calling for greater debt relief, the reality is that relieving bilateral debt might simply redirect funds to private creditors, rather than to the citizens of the Global South. The proposed ‘Common Framework for Debt Treatments’ that was agreed by G20 countries could see private sector inclusion, but we’ll have to wait until the G20 summit next month to see if this will make a meaningful difference to the countries preparing for default. In the meantime, more than 550 organizations from every region across the world have signed a letter calling for immediate debt cancellation to ensure that EMDEs are not facing many years of fiscal tightening to service the mounting debt burden.

Indeed, evidence suggests the private sector has been best protected in these responses. New analysis from Eurodad found that during the immediate emergency response, the World Bank earmarked almost 60 percent of the $14 billion Fast Track Covid-19 Facility to be allocated through its private sector arm, of which 68 percent of projects are targeting financial institutions and 50 percent of benefitting companies are either “majority-owned by multinational companies or are themselves international conglomerates.” This market-driven approach will only deepen pressures on fiscal space, pushing further privatization on vital health services, which have been depleted in recent years.

This exposes a dangerous double standard: while the IMF encourages wealthy countries to increase public investment now to stimulate a just and green recovery, studies by Eurodad, ActionAid and Oxfam have found that the support to EMDEs continues to expect future fiscal consolidation. In the long run, this could cost 4.8 times the amount that has been allocated to COVID-19 packages, further ruining any chance for a strong recovery that backs jobs, wages and public investment. As a consequence, more than 350 organizations signed a letter in the lead up to Annuals pushing the IMF to stop promoting austerity. The recent IMF Covid-19 Recovery Index from the GDP Center and UNCTAD identified encouraging signals from the IMF COVID response to support health and social protection spending, and so these recent studies expose the limitations of rhetoric alone. The Recovery Index also revealed a poor showing for green recovery support from the IMF, and with no mention of climate in the G20 communique, the ticking clock of climate change seems to be going unheard.

There is already evidence that the current approach has deepened existing inequities, with billionaires increasing their wealth by almost a third as millions lose their jobs. While the virus was not man made, policy decisions are. Ambitious ideas like those detailed in the TDR are needed now, such as an Independent Developing Country Debt Authority, an independent CRA, and a multilateral approach to corporate tax that can redirect resources to Southern budgets. The challenge now is to close the gap between rhetoric and reality, and push the international community to deliver on their stated aims to combat the virus, protect the vulnerable and mount a just and green recovery for all.

In a video interview, Richard Kozul-Wright, Director of the Globalization and Development Strategies Division at UNCTAD, explains the significance of the Annual Meetings and what to watch for in the weeks and months ahead: