Risky Business? Effective Environmental and Social Protections for the Belt and Road Initiative in Indonesia

By Rebecca Ray

As one of the world’s richest homes for biodiversity and one of the top recipients of Chinese finance and investment, Indonesia is in a crucial position for managing the economic, social and environmental benefits and risks of participating in China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

In a new working paper, researchers from the Boston University Global Development Policy Center and the University of Indonesia Research Center for Climate Change assess the environmental risks of Chinese FDI projects across Indonesia associated with the BRI by examining on-ground changes in vegetation cover. The authors conclude that because of the great variety of impacts across sectors, Indonesia could benefit from a regulatory framework focused on each sector’s risks and benefits, rather than an across-the-board relaxation of protections like the one presented in Indonesia’s recent “omnibus” Job Creation Law.

Identifying environmental and social risks from BRI projects in Indonesia

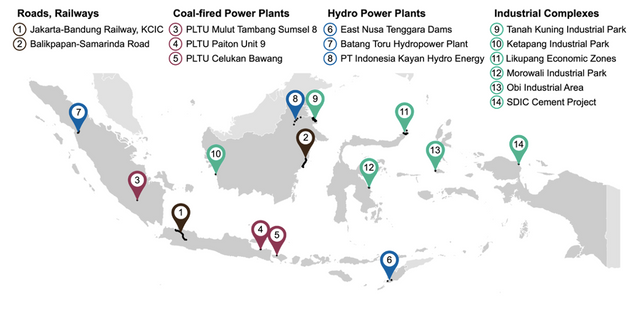

The research team identified 14 Chinese investment and finance clusters across Indonesia, including projects in planning and those already in operation, as shown in Figure 1. The sample was chosen to include the most representative sectors, including a railway, a road, three coal-fired power plants, three hydropower clusters (with a total of five individual dams) and six industrial complexes, distributed across a wide geographic area of the Indonesian archipelago.

Figure 1: Identified BRI Clusters in Indonesia, by Sector

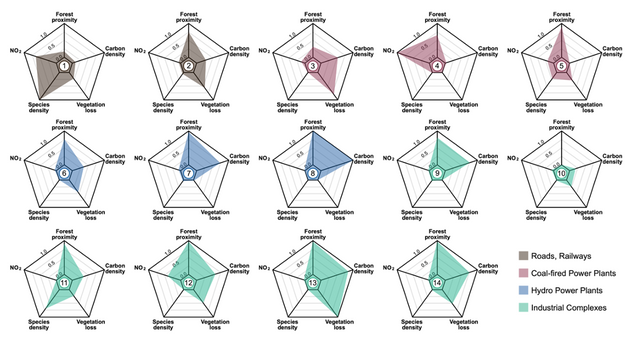

To track the environmental risks for each of these clusters, researchers measured risks across five environmental variables: vegetation loss in the surrounding area, carbon density of each area prior to construction, proximity to primary forest, density of threatened species and observed NO2 air pollution near each project. For each variable, results were normalized from values of zero to one, with the highest risk scored with a value of one. Figure 2 shows each cluster’s scores across the five environmental risk categories on the resulting zero-to-one index.

Figure 2: Normalized Results of Environmental Risks Across BRI Clusters

Risks to Indigenous communities were tracked qualitatively, across three categories of potential impact: health risks due to air or water pollution, ecosystem services losses to livelihoods and/or cultural heritage due to biodiversity loss and community displacement due to flooding or involuntary resettlement for construction. Of the 14 clusters, 11 were found to pose risks in at least one category. These three categories of risk were distributed evenly: six projects were found to pose each type of risk, with several projects posing multiple types. Two projects pose all three types of risks: the Morowali and Obi Industrial parks. In each of these cases, deforestation may bring livelihood loss as well as community displacement, and pollution associated with mineral extraction residue (tailings) bring risks of air and water pollution.

Different sectors, different risks

Across the identified environmental and social risks, commonalities emerged for each sector.

For example, hydropower projects were likely to be located near primary forests with high carbon density, potentially the net benefits of these projects for climate change mitigation. Hydropower projects were also more likely to pose the risk of displacing Indigenous communities through flooding. These results show that Indonesia’s hydropower planning process could benefit from a greater emphasis on “ ” analysis of economic, environmental and social benefits and risks when considering where to locate a new dam.

Industrial complexes were highly likely to be located near intact forests with high carbon density, resulting in vegetation loss. Their likely risks to local Indigenous communities include not only human health impacts through air and water contamination but also indirect impacts through diminished ecological services via deforestation and species loss. As with hydropower dams, the choice of location for industrial parks is a major factor in determining impacts, and both communities and the ecosystems that support them could benefit from greater consideration in project placement.

Coal-fired power plants showed significant variation in NO2 emissions, with larger plants associated with many times more air pollution, identified at much greater distances from the plants themselves, compared to smaller plants. For example, the town of Besuki (approximately 10 kilometers east of the largest coal-fired power plant in this study) faces NO2 levels many times higher than populations immediately adjacent to smaller coal-fired power plants. Thus, it is important to consider a wider range of potentially affected communities when planning larger projects.

Calibrating policy flexibility for varied risks

As a hotspot for both biological and cultural diversity, Indonesia should take special care to manage environmental and social risks from investment projects. Inadequate management of these risks may dampen the economic benefits brought by this activity, through lost traditional livelihoods and ecological services, and the costs of remediation.

Unfortunately, BRI host countries can impede effective environmental management under pressure to maintain “investment friendly” policies. In Indonesia, the enactment of the “omnibus” Job Creation Law (No. 11 of 2020) is expected to provide such an environment. As a recent study by the same research team finds, the Omnibus Law reforms many social and environmental protections in the name of attracting investment and generating employment. While it may be appropriate to simplify permitting processes for relatively low-impact sectors, the sweeping approach of the Omnibus Law is mismatched in scope for the risk contours presented to Indonesia’s ecosystems and the communities they support. However, as the results of the new working paper make abundantly clear, it is important to consider the varied impacts of different sectors of projects.

Read the Working Paper*

Never miss an update: Subscribe to the Global China Initiative Newsletter.