The 80th Anniversary of the Bretton Woods Conference is a Chance for Stock-taking—and Increasing Ambition

In July 1944—80 years ago—delegates from 44 nations met in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire.

Over the course of three weeks, they designed an agreement that led to the establishment of the Bretton Woods institutions, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD), which was later joined by the other institutions of the World Bank Group. The original agreement also considered trade to be a key pillar of the international financial architecture they were building, but the multilateral institution for trade was established later, with the General Agreement on Trade and Tariffs created in 1947 and the World Trade Organization (WTO) founded in 1995.

The World Bank, IMF and WTO remain at the core of the international financial architecture today, marking the durability of the legacy of the Bretton Woods Conference.

But the world has changed significantly since 1944—much of the world was colonized at the time, the world’s population and economy have grown dramatically in the last 80 years, and the gravity of the climate crisis has become evident. The 80th anniversary of the Conference provides an opportunity to evaluate whether the global economic governance system has kept up with a changing world.

A new flagship report synthesizes the work of the Boston University Global Development Policy Center (GDP Center) on global economic governance focused on the Bretton Woods institutions. The report finds that, while the Bretton Woods institutions established a rules-based, multilateral system of global economic governance, this system is in urgent need of fundamental reform.

Building on GDP Center research on the three key pillars of development finance, financial stability and trade, the report finds that three recommendations hold across all the pillars: the multilateral global economic governance system needs to be bigger, it needs to be better and it needs to be more inclusive. In practice, this means scaling up resources for financial stability and development finance, overhauling lending practices and priorities at the Bretton Woods institutions, and enhancing voice and representation across all pillars of the Bretton Woods institutions.

Financial stability and the IMF

The IMF, the only global, multilateral rules-based institution providing balance-of-payment support, is crucial for maintaining international financial stability and preventing financial crisis contagion in a highly globalized system. However, the Global Financial Safety Net (GFSN) – the network of institutions aimed at supporting countries during times of financial distress including the IMF, regional financial arrangements (RFAs) and bilateral currency swaps – remains skewed against lower-income countries. The expansion of RFAs and swap lines means that the IMF only accounts for 27 percent of the GFSN, but lower-income countries are largely excluded from those resources.

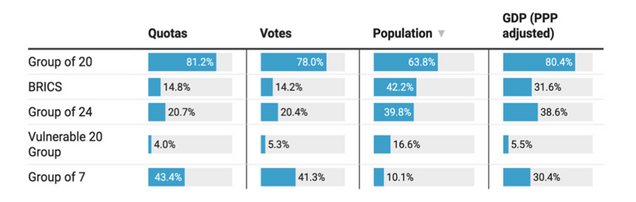

Within the IMF, as shown in Figure 1, developing countries receive a significantly smaller share of quotas and votes than their share of the global population and economy. In addition to largely determining a country’s votes in the IMF, quotas also determine levels of access to IMF finance and Special Drawing Rights (SDRs) allocations. The result of a GFSN that is flawed both in representation and access to resources is that developing countries often receive insufficient protection against financial crises and the support they do receive relies excessively on procyclical conditionality.

Figure 1: IMF Quotas and Voting Shares Compared to Share of Population and Global Economy, by Grouping

Accordingly, multiple reforms to the IMF are needed. First, quotas need to be significantly increased so that the IMF is adequately resourced, but members also need to realign quotas to better represent developing countries.

Second, the IMF should build on small signs of progress towards an institution that encourages an investment-led approach to climate and development challenges, including its climate strategy and the launch of the Resilience and Sustainability Trust, its relatively rapid response to the COVID-19 pandemic, and the 2021 issuance of $650 billion of SDRs.

Third, the IMF must reform its flawed Debt Sustainability Analyses to consider the level of spending required to meet development and climate goals, as well as climate shocks. Fourth, the IMF should eliminate surcharges, which are procyclical and exacerbate debt vulnerabilities.

The World Bank and development finance

Multilateral development banks (MDBs) have been an important source of low-cost, long-term finance and expertise to developing countries around the world. When including national development banks and regional financial institutions, the collective balance sheet of development finance institutions totals around $24 trillion in assets.

MDBs have expanded to focus on social sectors in additional to infrastructure, and they have also significantly reformed their safeguards and standards to ensure that the negative implications of lending are minimized. However, they are yet to find the right balance between avoiding negative impacts and enabling country ownership of programs.

MDBs must address three central concerns if they are to meet 21st-century challenges.

First, in a context where emerging market and developing economies other than China need to mobilize upward of $3 trillion annually by 2030 to meet their development and climate goals, MDBs must significantly scale up their financing. MDBs should implement measures to optimize their balance sheets, reform capital adequacy frameworks and, where necessary, pursue capital increases. While MDBs have made private capital mobilization a cornerstone of their financing strategies, assumptions regarding the ability of public capital to crowd in private capital continues to be over-optimistic.

Second, MDBs must increase the representation of developing countries if they are to preserve their legitimacy.

Third, MDB lending has a mixed record of promoting growth, and MDBs must do more to ensure their lending results in green and socially inclusive structural transformation.

The WTO and trade

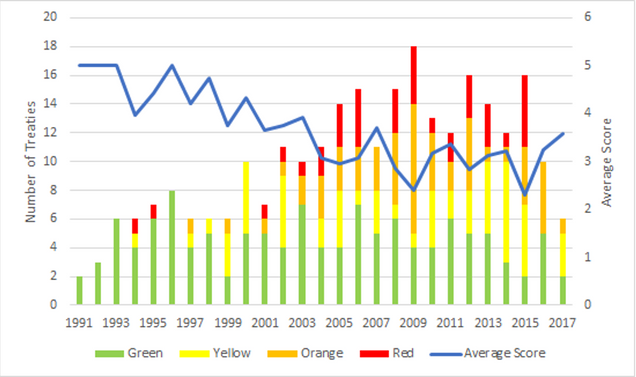

In the 80 years since the Bretton Woods Conference, the volume of global trade has boomed, coinciding with a rapid decrease in the percent of people living in poverty, vast improvements in maternal and child health, and many other social welfare improvements. Countries like South Korea and Taiwan achieved rapid export-led growth. While trade and investment liberalization has contributed at least in some ways to economic growth, the relationship is nuanced and has also come with costs, such as the decline of domestic policy space, as seen in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Shrinking Policy Space Through Trade Treaty Commitments – Illustrative Graph (Capital Flows Provisions)

Note: Green = Treaties with no commitments to liberalize capital account transfers, or a narrowly circumscribed commitment with broad exclusions/exceptions and no ISDS enforcement. Yellow = ‘Either’ treaties with a limited scope free transfers commitment, some policy and/or prudential exceptions and no ISDS, ‘or’ treaties with broad scope, as well as exceptions and no ISDS. Orange = ‘Either’ treaties with a broad free transfers commitment, broad policy and/or prudential exceptions and ISDS with limits, ‘or’ treaties with limited scope, some exceptions, and unconstrained ISDS. Red = Treaties with broad free transfers (2–3) commitments, a lack of general safeguards for macroeconomic crises and ISDS.

Several major challenges demand reform of the global trading system.

First, the global trading system should reverse some worrying trends that have emerged since the establishment of the WTO. At every subsequent ministerial following the formation of the WTO, there have been fewer and fewer areas of agreement, and countries have increasingly turned to bilateral and regional trade agreements that focus more on behind-the-border harmonization than trade negotiations’ traditional focus of lowering tariffs.

Second, trade rules have become insufficiently flexible for developing countries. They constrain measures that governments have historically used for the public purposes of development, public health, the environment and more, and they also make it more difficult for countries to maintain financial stability, to maintain and expand fiscal space and to intervene to restructure their economy in line with their development priorities.

Third, developed countries are increasingly disregarding global trade rules. While this may lead to greater policy space for governments, it also leaves the Global South vulnerable to the economic impacts of unilateral policymaking.

To revitalize the global trading system and avoid mistakes of the past, countries must agree to a healthy balance of multilateral cooperation and domestic policy space. The WTO Appellate Body must be revived to prevent a ‘might makes right’ trading system, but procedural and substantive reforms will be necessary.

Further, investor-state dispute settlement should be rolled back, which could save governments from as much as $340 billion in claims from oil and gas investors if they take climate action to keep warming below 1.5ºC.

Last, a wider range of reforms can ensure the global trading system facilitates green and socially inclusive development. These include increasing tariffs on fossil fuels and reducing them on renewable goods and reforming intellectual property and other trade rules to facilitate the diffusion of climate-friendly technology.

Conclusion

Over the years, the Bretton Woods institutions have served as an anchor of the global economic governance system, but the mounting global challenges and the intersecting crises of the early 2020s require an ambitious multilateral response. As this report demonstrates, these institutions can and must play a bigger, better and more inclusive role in supporting sustainable development and climate resilience.

The challenges confronting countries today provide the Bretton Woods institutions and their members with an important opportunity to transform these institutions to meet the needs and aspirations of people around the world.

*

Read the ReportNever miss an update: Subscribe to the Global Economic Governance Newsletter.