Summer in the Field: Understanding Gendered Mobility in Urban Ethiopia – Insights from a Pilot Study

Imagine navigating a bustling city like Addis Ababa, where the aroma of coffee and teff mingles with the dynamic rhythm of daily commutes. Yet, amidst this vibrancy, there lies a critical issue that often goes unnoticed: the unequal access to transportation experienced by different segments of the population.

The focus of a recent study by Anastasiia Arbuzova, Mahesh Karra and coauthors provides valuable insights into how targeted transportation surveys can start to evaluate gender disparities and increase representation.

As part of my 2024 Summer in the Field Fellowship Program, I traveled to Ethiopia, coded CommCare surveys and put in place evaluation mechanisms to analyze a pilot transport study. This blog post delves into the pilot study’s preliminary findings and how these insights could guide the development of a larger public sector intervention. By examining the impact of economic incentives on mobility and surveyed behavior, my research uncovers critical data that could reshape transportation systems in Addis Ababa and beyond.

The study began with a clear objective: to study the extent to which mobility and travel demand vary by gender, particularly for women, with a focus on translating our work on the introduction of on-demand, private transport to the public transport sector. My primary focus was to understand what the best way of surveying and incentivizing survey participants would be to reliably map the gender disparities in transportation access.

Addis Ababa, Ethiopia’s capital, provided a unique setting for this research. Known for its relatively developed transportation infrastructure—including buses, one of the few metro systems in Africa, and ride-hailing apps for booking private cars and taxis—the city offered a great opportunity for studying the impacts of transport services. The initial project aimed to assess whether introducing high-quality private transport services would lead to a more equitable distribution of transportation resources and how women’s mobility patterns might shift as a result.

This summer, the research focus shifted to leveraging the insights from the private sector to guide a broader public sector intervention, incorporating buses and metros, facilitated through data analysis and coding. The research included a quantitative pilot study surveying a small sample of Addis respondents’ daily travel (number of travels, transfer, distance, reason for travel, cost and more) through short SMS, call or Telegram-based surveys. The goal of this data was to help inform the design of a larger transport intervention to expand the study’s scale into the public sector where there is higher demand.

Impact of economic incentives

The research randomly divided the hundreds of study participants into three survey groups: Fixed, mixed and initial subsidy incentive groups.

In the fixed incentive group, which served as the baseline for comparison, participants received a fixed transfer of 25 Ethiopian Birr (ETB) upon completing each travel survey. This straightforward incentive was designed to measure the basic response to monetary compensation without additional complexities.

The mixed subsidy group, on the other hand, received a more variable travel subsidy based on their reported travel expenses. Members of this group were offered the same fixed amount of 25 ETB for completing each survey, but they also benefited from a 50 percent refund of their travel costs, with a cap of 200 ETB per week. This approach aimed to incentivize participants to report their actual expenses while still providing a guaranteed base payment.

Lastly, the lump sum travel subsidy group received a daily fixed amount of 25 ETB for each survey completed, along with a one-time travel subsidy of 200 ETB, which was granted regardless of their reported travel costs, on the day of their first completed trip survey. This structure was intended to evaluate the effectiveness of a larger upfront incentive in motivating participation and data reporting.

The pilot study’s goal was to find which would be the best incentive to continue the survey truthfully. Preliminary expectations suggest that the second group, which received daily travel subsidies, might report higher travel costs, potentially leading to less accurate data. However, this group was also anticipated to show higher participant retention rates. These insights could be pivotal for designing larger-scale public sector interventions, highlighting the trade-offs between participant retention and data accuracy.

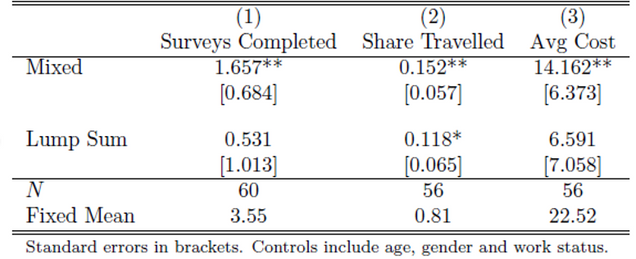

Table 1: Comparison of Incentives, Phone Surveys

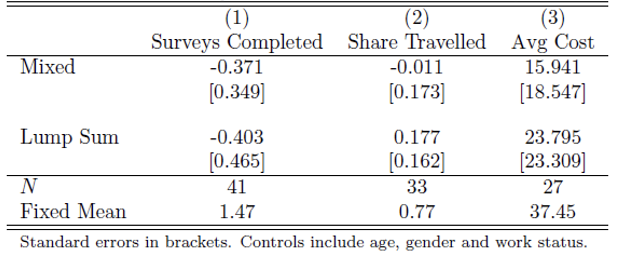

Table 2: Comparison of Incentives, SMS Surveys

When comparing the two test groups to the fixed incentive group on the phone survey responses, we observe that the mixed incentive group completed the most amount of surveys, 1.657 times more than the fixed incentive group, keeping all other factors constant (including age, gender and work status). Moreover, compared to the lump sum and fixed incentive groups, it seems mixed incentive groups not only had a bigger incentive to pick up the phone and complete the phone surveys but also had an incentive to report higher average travel costs. This data raises questions whether the mixed incentive would be good to use in the scaled-up study, as it may bias respondents into overreporting travel costs.

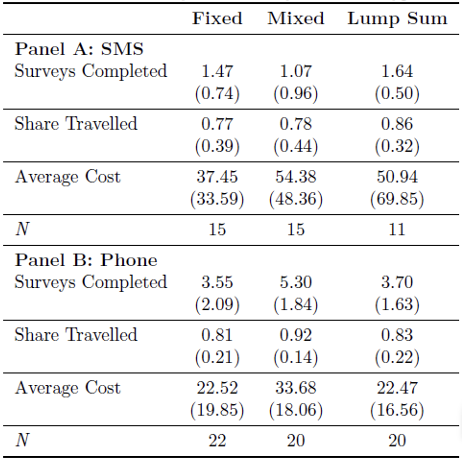

Comparatively, SMS surveys show a different conclusion. Both the mixed and lump sum groups had lower survey completion rates than the fixed group, keeping all other factors constant. In comparison to phone surveys, respondents have less incentive to answer SMS surveys. The data also shows a difference in average reported costs between SMS and phone survey respondents. Evidently, the average cost reported is much higher in SMS surveys than in phone call surveys.

SMS vs. telegram messaging vs. phone surveys

An unexpected but crucial finding was the difference in survey response rates between SMS and Telegram messaging platforms. Contrary to expectations that smartphone users would prefer Telegram, SMS surveys were more effective. This preference for SMS can be attributed to its familiarity and perceived security, as many individuals use SMS for transactions and communications, including e-payments on platforms like Telebirr. Higher confidence led to higher response rates in SMS surveys sent than Telegram and arguably more accurate location answers.

In contrast, Telegram surveys were perceived as less secure and less familiar, akin to using WhatsApp, which some users might find less comfortable due to privacy concerns and pin-dropping ability. This finding underscores the importance of ensuring that survey platforms are accessible and acceptable to all for study effectiveness and accuracy on larger-scale transportation interventions.

Altogether, phone surveys seem to be the preferred method of surveying respondents both for survey completion and the accuracy of average costs reported.

Table 3: Summary Statistics by Incentive Type

Scaling up: From private to public sector

The insights gained from the pilot study are guiding the development of a larger public sector intervention. This next phase aims to extend the successful elements of the small-scale survey findings to public transportation systems, such as buses and metros. By applying the lessons learned to the large-scale intervention, the goal is to create a more inclusive and equitable transportation network that addresses the specific needs of women and other underserved groups.

Key considerations for scaling up initiatives involve several important factors. One crucial aspect is the socio-economic evaluation, which assesses how groups benefiting from fixed and travel subsidy incentives compare in terms of data reporting quality and truthfulness. This evaluation can reveal significant insights into the integrity of the data collected from these groups.

To deepen this analysis, using STATA to create a “lying” variable can help identify discrepancies in reported data. This approach allows researchers to investigate whether men or women are more likely to provide inaccurate information. Additionally, analyzing variables, such as the frequency of work-related travel and reported travel distances, can shed light on gendered mobility patterns. For instance, understanding whether men report longer distances traveled compared to women who commute can highlight underlying trends in travel behavior between genders.

Another critical consideration is the accessibility of the survey platform. Ensuring that the survey is easily accessible, whether through messaging or calls, is essential for the reliability of the public transport survey. By prioritizing accessibility, we can enhance participation rates and improve the overall quality of the data collected.

The findings from the pilot study provide a strong foundation for developing a comprehensive public-sector intervention that builds on successful private-sector models and includes insights on survey method preferences. In considering the lessons learned on survey accessibility, economic incentives and preferred survey platforms, future initiatives can be tailored to create a transportation system that is inclusive, safe and efficient for all residents of Addis Ababa.

By continuing to analyze and apply these findings, we can work towards a future where transportation is no longer a barrier but a bridge to opportunities and empowerment for all.

*

Learn more about the Summer in the Field Fellowship Program.