10 Charts to Illustrate a Structuralist Perspective of Developing Economies’ Debt

Over the past few years, public debt has returned to the spotlight, especially in developing economies. Once seen as a tool for economic development and crisis response, debt has been increasingly perceived as a significant risk to economic stability and growth. With global shocks like the COVID-19 pandemic, rising interest rates in developed economies, a deepening climate crisis and geopolitical tensions and conflicts, fears of a looming debt crisis in developing economies similar to that of the 1980s and early 1990s have reappeared.

However, discussions on debt and policy space in developing economies tend to focus on conventional metrics, especially public debt-to-gross domestic product (GDP) ratios that often do not distinguish between foreign and domestic currency denominated liabilities. This approach risks misunderstanding both the nature of the current debt risks and the range of policy options available for different countries.

In a new working paper, I argue that external debt sustainability in developing economies should be analyzed through the balance of payments constraint lens, not merely fiscal space or arbitrary public debt thresholds. Managing external debt involves more than controlling its absolute size; it requires managing its composition, particularly currency denomination, and ensuring sufficient foreign exchange net inflows and reserve accumulation.

Here, I outline how external debt has evolved, why the balance of payments matters more than debt-to-GDP ratios and what this means for policymaking in developing economies.

What Has Changed in External Debt in Developing Economies?

While concerns about rising debt levels are not new, the structure of external debt has changed significantly since the 1980s and 1990s. The following trends stand out.

Debt Ratios Are Historically Low but Have Shifted Towards More Expensive Debt

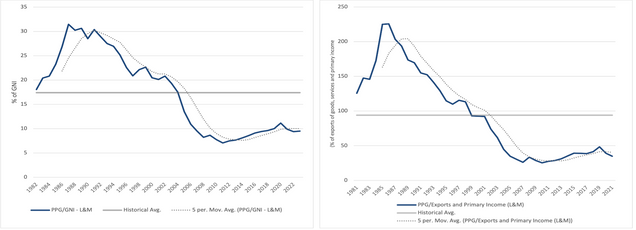

Measured against income or exports, external public and publicly guaranteed debt (PPG) in many developing economies is lower than in the 1980s and 1990s (Figure 1). Even with the post-2008 increase, levels remain low by historical standards. But if debt levels aren’t historically high, why are concerns so prevalent?

Figure 1: External Debt Ratios of Low- & Middle-Income Countries

Traditionally, between 1987 and 2010, developing economies have relied heavily on loans from multilateral institutions like the World Bank or bilateral agreements with other governments. These official loans typically have longer maturities and lower interest rates than debt from private creditors.

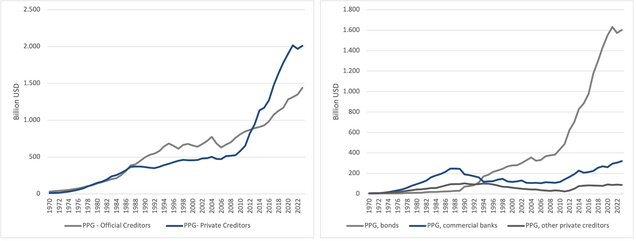

Yet, more recently, private lending, through bond markets, has become the dominant source of external financing (Figure 2). Although the increase in private borrowing means an increased supply and access to foreign currency for developing economies, this also exposes these economies to higher borrowing costs and shorter debt repayment periods, making them more vulnerable to fluctuations in international interest rates and changes in global investors’ sentiments.

Figure 2: Composition of External Debt of PPG in Low- & Middle-Income Countries

The Role of Domestic Currency Debt and Foreign Reserves

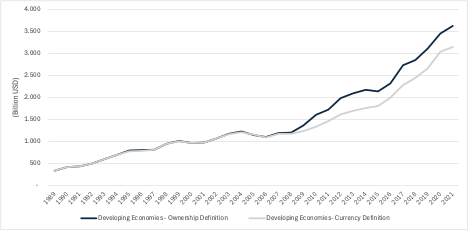

A key feature of the World Bank’s external debt database used in most policy discussions is that its definition is based on the ownership concept. In this definition, external debt is owed to nonresident creditors and is repayable in foreign and domestic currencies. In a currency definition, external debt is defined as foreign-currency-denominated debt.

Historically, especially in developing economies, governments borrowed almost exclusively from foreigners through foreign currency-denominated liabilities, with domestic currency-denominated debt predominantly held by residents. This led to an overlap in the definitions of external debt based on ownership and currency of denomination. However, as a positive development, some middle-income developing economies, a group of mainly middle-income developing economies that integrated into international markets during the 1990s, often called emerging market economies (EMEs), are now issuing debt in their own currencies to both national and international investors.

This matters because it reduces the risk of currency mismatch in the balance sheets of developing economies’ debtors. In the past, if the local currency depreciated, external debt services would spike. Now, this is not always the case. Figure 3 shows the growing gap between the two definitions of external debt.

Figure 3: External Debt Levels

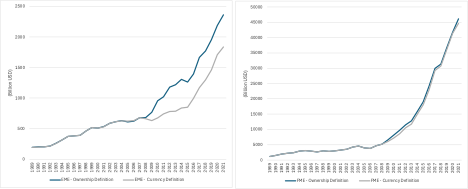

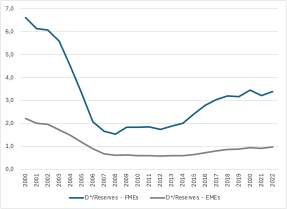

At the same time, many EMEs have accumulated more foreign reserves (Figure 4), which act as buffers against external shocks, helping countries navigate exchange rate fluctuations and sudden capital outflows. Additionally, countries with higher reserve levels relative to their external debt obligations are seen as less risky borrowers, which can help them access international markets at lower interest rates and improve their credit ratings.

Figure 4: International Reserves

A Tale of Two Divergent Stories

However, not all developing economies have presented these trends. Frontier market economies (FMEs), or lower-middle and low-income countries that joined global markets after 2008, haven’t built up as many reserves as EMEs (Figure 4).

Additionally, for EMEs (Figure 5a), there has been a noticeable divergence between the ownership and currency definitions of external debt since the early 2000s. For FMEs, on the other hand, the two definitions overlap closely, indicating that FMEs have predominantly continued to issue external debt in foreign currencies, making them particularly vulnerable to exchange rate fluctuations and external shocks (Figure 5b).

Figure 5: External Debt in Foreign and Domestic Currency

(a) (b)

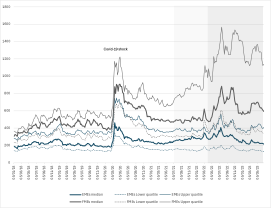

As Figure 6 shows, EMEs have broadly stabilized their borrowing costs after recent shocks, reverting to pre-pandemic levels. FMEs remain vulnerable, experiencing sustained, elevated borrowing costs for a longer period.

Figure 6: JPM EMBI Global Sovereign Spread

Why does Balance of Payments Matter More Than Debt-to-GDP Ratios?

Conventional wisdom on debt sustainability tends to focus on the total debt-to-GDP ratio. However, this measure alone can often be misleading. Since governments cannot be forced into default on obligations payable in their own currencies, which they issue, there is no clear threshold or “magic number” at which domestic-currency-denominated debt becomes unsustainable.

In contrast, a country’s ability to generate sufficient foreign exchange inherently poses limit to external debt denominated in foreign currency. Thus, what genuinely restricts economic policy and sustainable growth is the balance of payments constraint (essentially, an economy’s ability to finance necessary imports and meet its external financial obligations).

The balance of payments constraint consists of two interconnected dimensions: structural and financial. The structural dimension refers to an economy’s dependence on foreign technology and imported goods, reflected in a high import coefficient. However, this structural dependency alone does not necessarily limit growth if the economy can sustainably finance these imports.

The financial dimension then becomes critical precisely because it addresses how these imports are financed. According to the balance of payments constraint growth literature, an economy’s capacity to sustain external debt depends on its ability to generate enough foreign exchange.

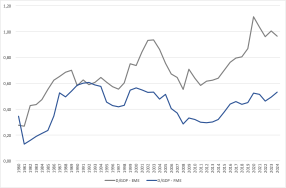

When we look at total public debt, as illustrated in Figure 7, EMEs present higher debt-to-GDP ratios than FMEs throughout the analyzed period. While EMEs show a pronounced upward trend in debt levels, especially from the mid-2000s onward, FMEs initially faced higher volatility in debt ratios, with peaks in the late 1980s and reductions through the Initiative for Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) and the Multilateral Debt Relief Initiative (MDRI) during the early 2000s.

Figure 7: Total public debt over GDP in EMEs and FMEs

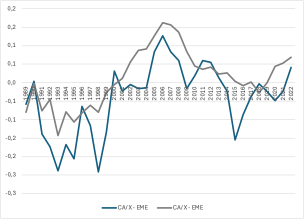

Despite having higher absolute public debt levels, EMEs appear less vulnerable when analyzed through balance of payment constraint indicators. In this approach, the following indicators help us understand external sustainability better. The first is the current account deficit over exports ratio (CA/X), which directly reflects a country’s immediate external financing needs, highlighting the dependency on external resources. A higher ratio signals increased vulnerability, indicating potential difficulties covering external obligations without continuous external financing. As Figure 8 shows, EMEs generally exhibit smaller deficits or even surpluses, reflecting their relatively stronger export capacities and lower immediate financing needs than FMEs.

Figure 8: Current Account over Export Ratio

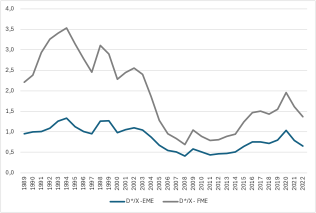

The second indicator is the stock of external liabilities denominated in foreign currency to export ratio (D*/X). This ratio measures the accumulated external debt relative to a country’s capacity to generate foreign exchange. A higher ratio can undermine creditors’ confidence, limiting further borrowing and increasing refinancing risks. Figure 9 shows that FMEs have historically maintained higher ratios compared to EMEs.

Figure 9: External Debt in Foreign Currency over Export Ratio

The divergence is even more pronounced if we look at the foreign currency denominated debt over reserves ratio in Figure 10. Although this ratio in FMEs improved from a very high starting point in the early 2000s, it has trended upward since the 2010s, signaling growing external vulnerabilities. EMEs, in contrast, display low and stable ratios, reflecting their substantial accumulation of international reserves and, consequently, stronger external financial resilience.

Figure 10: External Debt in Foreign Currency over Foreign Reserves Ratio

Thus, when analyzed using balance of payment indicators, FMEs exhibit higher vulnerabilities, which is also reflected in recent debt distress cases: out of the six more severe cases of default by financially integrated developing countries between 2020 and 2023, five were FMEs (Ghana, Sri Lanka, Suriname, Zambia and Ethiopia). The sixth country was Lebanon. According to an S&P report, three other financially integrated developing economies also faced episodes of sovereign distress during this period. However, cases involving foreign currency shortages lasting from a few days to five months that were resolved through restructuring without a formal declaration of default (Belize, Ecuador and Argentina) were excluded from this count.

Shifting attention from traditional debt-to-GDP ratios towards a structuralist balance of payments perspective indicates that while some developing economies genuinely face debt distress driven by external vulnerabilities, others retain more room for proactive, growth-oriented economic policies than conventional wisdom currently suggests.

Balance of Payment Constraints and Economic Policies

Using the balance of payments constraint framework also helps clarify the range of economic policies available to developing economies. When a country’s economic output is below this constraint (when the economy can safely increase spending without facing external financial difficulties), policymakers have room to stimulate economic activity through expansionary fiscal and monetary policies. However, monetary policy, in particular, can be tricky because domestic interest rates directly influence the balance of payments by affecting capital flows and exchange rates. Consequently, fiscal policy often becomes the more reliable tool to boost aggregate demand and pursue broader developmental goals.

Fiscal policy itself faces two critical limits: first, the balance of payments constraint sets a ceiling on the maximum output level and, thus, how much spending a country can sustainably undertake. Second, there are political limits tied to domestic concerns about rising interest payments, which often disproportionately benefit higher-income groups. While policymakers can address these distributional concerns by adjusting taxes on higher-income earners, the external constraint requires a more strategic, developmental approach. Targeted government investments that reduce reliance on imports and enhance export competitiveness can expand policy space and sustainably raise economic growth.

Conversely, when a country’s economic output exceeds the balance of payments constraint, simply implementing contractionary policies, such as public spending cuts, may not be effective. Reducing spending has political and social limits, and combining austerity measures with currency devaluation can lead to stagflation. Increasing interest rates to attract foreign capital might not work efficiently, especially during periods of global financial uncertainty. In this scenario, international institutions become crucial. They can help these countries manage foreign currency shortages without forcing them to abandon growth and development goals.

Today’s debt challenges do not seem uniformly widespread, which creates an opportunity: targeted debt relief and liquidity support can be both highly effective and relatively low-cost. But delay or inaction can risk contagion and if current pressures are met with rigid conditionalities and austerity, what is now a contained problem could spiral into a broader debt crisis.

Read the Working Paper*

Never miss an update: Subscribe to the Global Economic Governance Newsletter.