Humanists at Work: Margaret Litvin, Associate Professor of Arabic & Comparative Literature

Although Margaret Litvin went to graduate school to study Arabic, she didn’t expect she would end up as a professor. Now an Associate Professor of Arabic and Comparative Literature at Boston University, Litvin spent her undergraduate years focused on breaking into a different field: journalism.

“I worked a lot on my college newspaper, probably more than I worked on my schoolwork. I was sure that I wanted to be a journalist. That was kind of my whole life,” says Litvin.

Committed to a career in journalism, Litvin graduated from Yale and started work at The New Orleans Times-Picayune. Mere months later, Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin was assassinated by a right-wing extremist who opposed the Oslo Accords, a series of agreements between Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organization. “I realized that we Americans had no idea what was going on in the Middle East,” Litvin said.

Committed to a career in journalism, Litvin graduated from Yale and started work at The New Orleans Times-Picayune. Mere months later, Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin was assassinated by a right-wing extremist who opposed the Oslo Accords, a series of agreements between Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organization. “I realized that we Americans had no idea what was going on in the Middle East,” Litvin said.

As a journalist, she had started noticing that coverage of the region included a limited selection of quotes from Arabs—and that these were often incoherent or angry.“I thought, surely there must be smart people over there whom we’re not hearing from. There must be some voices from that region who don’t speak perfect English and therefore are not being interviewed, and are not finding their way into our media.”

Spurred on by this curiosity, Litvin went to graduate school to learn Arabic as a journalist, but ended up being drawn into academia instead. Her research grappled with the impact of another major geopolitical phenomenon: the Cold War. Though she was born in Russia and grew up speaking Russian, Litvin never expected to do anything with the language professionally until she began her dissertation and discovered the connections between Russia and the Arab world.

While working on her dissertation on adaptations of Hamlet into Arabic, Litvin was intrigued to find that Arab writers were interested in the same 1964 film adaptation of Shakespeare’s play that her parents watched in the 1970s Soviet Union. During the Cold War, many Soviet books and films were available thanks to cultural outreach programs, but Litvin noticed a genuine affinity for the Russian-language version of Hamlet.

“The film spoke to them, not because it was made available to them or shoved down their throat by somebody’s diplomacy, but because it fed some hunger that they had,” says Litvin. “And so that’s what I started to study. What is that hunger for Russian culture?”

This connection between the Soviet and Arab worlds has inspired much of Litvin’s research, including her latest book manuscript, Red Mecca: The Life and Afterlives of the Arab-Soviet Romance. She explains that the term “Red Mecca” is not a novel one. The term emerged in the 1920s and 1930s as political and social justice leaders from around the world drew inspiration from the Russian Revolution and converged on Moscow, their Red Mecca. In her manuscript, Litvin explores representations of the USSR in Arab literature, including an interesting archetype she calls the “Russian Girlfriend Fantasy” that appears in Arabic travel writing.

Arabic study abroad novels set in Europe “usually feature a man going from, let’s say, Lebanon or Egypt, to London or Paris, and meeting some kind of Susie or Katie who embodies the host culture and all of its virtues. She’s beautiful, liberated, freethinking, sexually available. It’s great, but she’s morally vacuous,” notes Litvin. “Travelers to Russia and then the Soviet Union tell a different story. The Russian woman is deep. She is spiritual.”

The Russian woman in Arabic literature becomes an extension of 19th century Russian literary rhetoric about women, acting as a moral sustainer of society. If Western women are shallow—and men can’t get it together—Russian women offer a sort of perfection. However, there’s a catch.

“You can’t ever really have her,” Litvin says. “She becomes a figure for Soviet internationalism. It’s the Soviet Union, the dream of communism itself that is ultimately so perfect and so unavailable.”

Figures like these are what draw Litvin to the connections between the Soviet and Arab worlds, and she hopes they might inspire more people to look for connections between Arabic literature and their own. She also believes that strong regional studies programs are the basis for transregional projects similar to her own research. A founder of Boston University’s major in Middle East and North Africa Studies, Litvin says Arabic literature courses have a lot to offer to a variety of students, including heritage speakers.

“Immigrant kids are interested in learning more about their own culture that maybe their parents never taught them,” says Litvin. “We also have a lot of international students from Arab countries who want a different perspective on the culture they grew up with.”

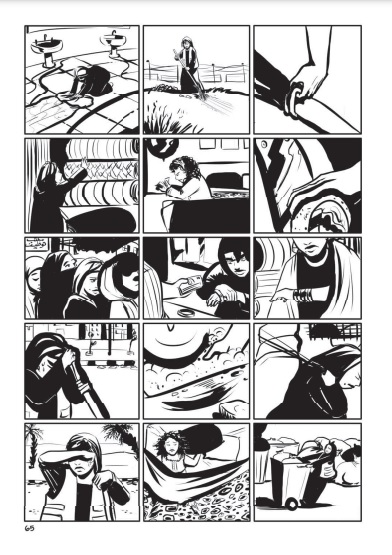

For students who did not grow up reading Arabic literature, Litvin points to several writers and resources as excellent starting points. Many writers from the Arab world also write in English, or they have works available in translation. Litvin recommends Nizar Kabbani for those who enjoy poetry, while she says Palestinian author Sahar Khalifeh, particularly her novel Passage to the Plaza, is a great place to start with prose fiction. In this age of the internet, she also says that blogs like Arablit.org can be great resources for discovering all that Arabic literature has to offer.

Like any other body of literature, Arabic literature is diverse. From graphic novels to sci-fi to poetry, Arabic literature has plenty to offer its readers.

“Whatever genre it is that you like, there are Arabs who like it and produce it too, and there are others who translate it,” Litvin notes.

Though she is now in the classroom instead of the newsroom she once imagined, Litvin continues to investigate the importance of individual stories and what they can tell us about the relationships between regions. She hopes that interest in Arabic literature and its transregional possibilities continues to grow. Exploring other languages’ literary traditions is one way to discover those voices Litvin realized she was missing years ago.