Prioritizing Gateway Cities in Massachusetts’ Transition to Renewable Energy

The energy transition is a vital economic development opportunity for industrial legacy cities.

Industrial legacy cities in Massachusetts stand to greatly benefit from participating in the state’s transition to renewable energy—including all the economic, social, and climate resiliency advantages that come with it. Offshore wind investments in New Bedford and Salem are expected to revitalize those cities’ maritime economies. A solar array on a former landfill in Springfield will provide electricity at a lower cost to both the municipality and low-income residents. The state’s transition to renewable energy infrastructure could be a ‘gateway to investment’ for cities like these if they were to receive targeted support to realize their energy transition goals, whether related to infrastructure or jobs, but historical challenges put them at a disadvantage.

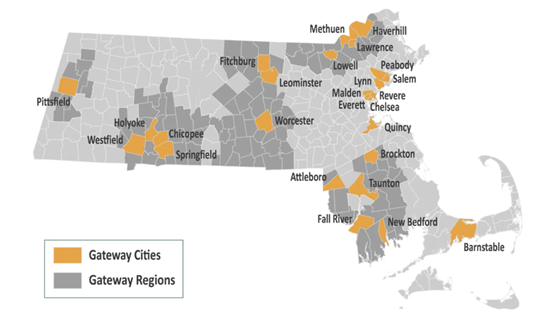

The Massachusetts legislature has designated 26 midsize cities that were historically the industrial engines of the state as Gateway Cities (see following figure). They received this designation for their potential to drive revitalization of the state’s regional economies, but they face greater social and economic challenges than other cities and often grapple with environmental injustices stemming from decades of unregulated industrial production. Gateway Cities have not caught up with the state’s shift to knowledge-based industries concentrated around Boston. While job growth in the Boston area reached 51 percent since the 1970s, Gateway Cities instead experienced job losses and by 2007 were home to 30 percent of the state’s residents living below the poverty line. This phenomenon is of course not unique to Massachusetts. Older industrial cities across the U.S. have not grown in population size for decades and have failed to increase jobs in new sectors, resulting in a rise in concentrated poverty, particularly among BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and People of Color) and immigrant communities.

Massachusetts Gateway Cities

massinc.org/our-work/policy-center/gateway-cities/about-the-gateway-cities

Initial achievements toward renewable energy

Despite these challenges, Massachusetts Gateway Cities have taken impressive steps toward achieving their energy transition goals. Highlights from five cities provide a sense of where they’re headed:

- Chelsea spearheaded the development of an innovative expandable microgrid, a project sponsored by the municipality and led by the community, with the support of GreenRoots and Green Justice Coalition.

- Holyoke closed down the state’s last coal-fired power plant, Mount Tom Power Station, through a community campaign that partnered with Community Action Works and Neighbor to Neighbor to address air pollution and public health impacts. The city simultaneously worked toward the development of a 17,000-panel solar farm, the largest in Massachusetts as of 2019.

- Everett Mayor Carlo DeMaria was among 150 city and town officials in July 2020 that called on Massachusetts to commit to 100% renewable energy, explaining that he was ‘proud to support a bill that encourages the elimination of fossil fuels in our communities.’ The Mystic Generating Station in Everett has been the state’s largest power plant for decades, emitting pollutants that contribute to climate change and high asthma rates, which have been shown to increase the risk of dying from the coronavirus. Efforts by local environmental organizations and residents against the gas-fired plant contributed to its slated retirement in 2024.

- Springfield has reduced its energy consumption by 26 percent and saved over $3.5 million in annual fuel costs by improving energy efficiency in schools, planting trees by the thousands, and switching to organic fertilizers in athletic fields. The city also installed a solar array on a former landfill that provides affordable electricity to hundreds of low-income residents.

- New Bedford is helping to build the local offshore wind industry, described by Mayor Jon Mitchell as a ‘generational opportunity’ to attract investment, create jobs, improve air quality, and save taxpayer dollars. As Energy Chair of the 2017 U.S. Conference of Mayors, Mitchell helped produce the New Bedford Principles, which called for federal energy-friendly tax reform for municipalities; incentives to promote microgrids, distributed generation, and energy storage systems; funding to modernize local grids and increase resilience to climate impacts; and other measures to deliver resources for local energy transition.

Promises and pitfalls

While these achievements spearheaded by Gateway Cities establish a trajectory toward building local clean energy economies, it’s unclear the extent to which they will receive the support they need to stay on this path and to accelerate their pace. A critical factor is the provision of resources from federal and state agencies.

In recent months, the Biden administration established a goal of increasing the country’s electricity generation to 45 percent solar power by 2050, and the Senate passed the historic bipartisan Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act. The infrastructure bill includes $73 billion for energy, largely to improve interstate infrastructure to support the transmission of clean energy, as well as funding for energy efficiency and environmental justice. Local governments will benefit from significant infusions to the Energy Efficiency and Conservation Block Grant, Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program, Energy Efficiency Revolving Loan Fund, plus electric charging and fueling infrastructure grants and assistance to implement building energy codes. A lot of the implementation of these federal programs will fall to states and municipalities, which maintain 90 percent of the country’s non-defense public infrastructure. The Brookings Institution predicts that ‘states and localities will be lush with new resources’, and the bill’s effectiveness will be determined by how those resources are used.

Federal legislation has usually channeled funding to the largest cities or through states, but industrial legacy cities throughout the U.S. will require an approach that reaches small and resource-challenged cities. A recent ISE paper argues that given the massive size and diversity of the country and economy, states should indeed be in the driver’s seat, partnering with industry in implementing climate goals enacted by the federal government. But even large U.S. cities suffer from insufficient funding that delays critical infrastructure investments. And states do not always make decisions that benefit industrial legacy cities. For example, representatives of New Bedford and Fall River pointed out that in Massachusetts’ 2019 bidding round for offshore wind projects, the state Department of Public Utilities chose a cheaper project over one that would have included more economic development benefits, including a factory with up to 200 jobs. Critiques of the federal infrastructure bill point to gaps that will directly affect Massachusetts Gateway Cities, such as a lack of strong investment in workforce training and not enough funding for sustainable mass transit. Commenting on the bill, the U.S. Conference of Mayors argued that ‘committing to more localism can be accomplished by investing directly in our cities.’

Achieving inclusive economic growth in older industrial cities will require investing not only in technological capabilities, but also expanding economic opportunities for disadvantaged communities and preparing a diverse workforce. Massachusetts’ growing clean energy industry has contributed close to 40 billion to the state economy and increased employment by 89 percent (54,000 workers) over the decade leading up to 2019. But close to half of this growth has been concentrated in the northeastern region surrounding Boston, with less investment in other parts of the state. Latinx and Asian workers and veterans in Massachusetts have entered clean energy jobs more than other sectors, but Black and female workers remain underrepresented. Without targeted investment, the people that inhabit Gateway Cities will not gain sufficient access to resources for renewable energy and climate resiliency and will continue to be left behind in the clean energy transition.

While the major federal packages continue to be debated, Gateway Cities are receiving one-off grants from state and federal agencies. Chelsea received state funding to install a battery storage system and solar at City Hall under the Municipal Vulnerability Preparedness Program. The Green Futures Act proposed in February 2021 sought to allocate $3 million annually for green infrastructure to Lawrence, Brockton, and Quincy. And Massachusetts expanded its tree-planting program aimed at improving quality of life, cooling neighborhoods, and lowering energy bills in Gateway Cities. At the federal level, the U.S. Department of Energy launched a new initiative to help communities faced with disproportionate impacts of fossil fuels pursue clean energy economic opportunities. And Springfield received federal funding under the Water Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act to deliver renewable energy to the city’s water treatment plant.

These are solid steps forward, but may not be enough for Gateway Cities to keep up with more affluent cities and towns in Massachusetts. In a recent ranking of the performance of 40 cities and towns on climate action around Boston, Salem was the lone Gateway City in the top ten, due to its climate partnership with the more affluent town of Beverly. If the state’s clean energy transition is to achieve lasting action on economic development and energy justice, Gateway Cities and their residents must become a priority investment.

Rebecca Pearl-Martinez, Executive Director of the Boston University Institute for Global Sustainability, is a consultant to UN agencies and international organizations on the social dimensions of renewable energy and climate change policy. She is currently investigating urban energy transition and auction design in Chile as part of Ph.D. research at the Department of Geography at Durham University in England.

The opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the Boston University Institute for Global Sustainability.