Tailoring BSA/AML Risk Assessment to Combat Forced Labor in Supply Chains

By: Shirley Duquene (BUSL ’21)

Forced labor generates an estimated $150 billion dollars of profits annually; these illegal proceeds are likely to pass through the banking system. Thus, it is crucial that financial institutions identify, monitor, and report transactions suspected to involve forced labor proceeds both in order to comply with anti-money laundering laws and to assist in global efforts to protect vulnerable workers. This blog post will explain how financial institutions should incorporate indicators of forced labor into their existing risk assessment processes.

Background

Freedom from enslavement is a basic human right. The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights establishes the “right of everyone to the opportunity to gain his living by work which he freely chooses or accepts” and fair wages, in Articles 6 and 7. However, the International Labour Organization (ILO) estimates that 40.3 million people were victims of modern slavery on any given day in 2016, and that profits generated by forced labor amount to $150 billion USD annually. While sex trafficking and forced marriage are also types of modern slavery, this paper will only address forced labor and debt bondage.

Eliminating forced labor requires an active global effort on the part of diverse players—corporations, non-profits, governments, and financial institutions. Because illegal profits generated by forced labor are often funneled through the global financial system, financial institutions have a significant role to play in the fight against modern slavery.

Financial institutions already deter and help prevent money launderers and terrorists from gaining access to the United States (U.S.) financial systems through Bank Secrecy Act (BSA)/Anti-Money Laundering (AML) compliance programs. While the BSA does not apply to foreign offices or branches, U.S. financial institutions are expected to comply with U.S. standards at their branches and offices worldwide.

The USA PATRIOT Act requires all banks to have systems in place which:

- Identify their customers and perform risk-based customer due diligence (CDD);

- Monitor and detect suspicious activities; and

- File suspicious activity reports (SARs).

These three requirements can be used to deter and prevent the laundering of illegal forced labor proceeds. CDD processes and procedures help banks identify clients who are at a higher risk of transacting with proceeds of forced labor. Closely monitoring activities consistent with forced labor transactions using a risk-based approach can help financial institutions effectively detect potential instances of money laundering. SARs (reports sent by banks to enforcement authorities) are required to be filed if the bank “knows, suspects, or has reason to suspect that the transaction…[m]ay involve potential money laundering or other illegal activity,” such as forced labor. However, there are far fewer unique financial flows in forced labor trafficking cases than in sex trafficking or drug trafficking because of “the lower amounts involved, and the prevalence of gradual enrichment of traffickers.” While figures suggest that “[l]ess than 3,400 of the approximately 2.3 million SARs filed in the US in 2019 were identified as related to modern slavery,” tailoring a BSA/AML risk assessment to help identify forced labor in supply chains could lead to a sharp increase in related SARs. By providing critical information to law enforcement, thereby bringing the criminals trafficking in forced labor to justice, this could reduce the overall instances of forced labor in the future.

Forced Labor in Supply Chains

Businesses can pose a significant threat to the human rights of those who work within their supply chains, especially the approximately 16 million hidden workers who are performing forced labor. Forced labor encompasses labor trafficking, child labor, debt bondage or bonded labor as well as traditional slavery. Debt bondage, for example, occurs when a laborer may be obliged to pay an exorbitant recruitment fee (usually with debt or loans) to a trafficker in exchange for a promised high-paying job, accommodation near a worksite, and help with a visa process. Laborers may then leave their home countries or places of residence under the illusion of a better, lawful employment overseas, with a significantly higher wage. Only upon arrival do they realize that they have been fraudulently induced to accept the job offer—that they will be forced to live in poor quality, company-controlled housing, work longer hours than expected, and receive little to no pay as compensation. A victim of forced labor is exploited for profit usually “through the use of violence or intimidation or by more subtle means such as manipulated debt, retention of identity papers or threats of denunciation to immigration authorities.”

Connection Between Forced Labor and Money Laundering

Money laundering is the crime of using financial transactions to “clean” proceeds arising from unlawful activity, conduct, or offenses. Human trafficking, illegal restraint, kidnapping, and fraud—all common in forced labor flows—are included as predicate offenses to money laundering by the U.N. Convention against Transnational Organized Crime and the Financial Action Task Force (FATF), which sets the de facto AML global standard. Forced labor profits are illegal proceeds that launderers seek to “clean” through a sequence of transactions in order that the proceeds then appear to be legal. Therefore, to effectively mitigate the risk of being used to launder illegal proceeds, financial institutions should seek to identify forced labor financial flows while designing and implementing their BSA/AML risk assessment. In doing so, financial institutions will be in a better position to put the necessary controls in place both to identify which customers require enhanced due diligence and to detect suspicious activities arising from forced labor. The financial institutions will then be able to directly assist law enforcement in the prosecution of these crimes by filing relevant SARs.

BSA/AML Forced Labor Risk Assessment

This paper addresses money laundering risks specific to forced labor flows. No single risk factor is determinative of forced labor. Rather, banks should assess risks comprehensively when evaluating whether enhanced customer due diligence is needed or further transaction due diligence should be conducted to determine if a SAR should be filed. The following factors should be considered when assessing the risk that laws surrounding forced labor have been violated.

High-Risk Geographies

While geographic risk alone does not determine a customer’s or transaction’s risk level, financial institutions should identify which locations pose a higher risk of forced labor and evaluate the specific risks of doing business there. Indicators that may be used to categorize high-risk geographic locations include:

- Countries with a high prevalence of modern slavery according to the Global Slavery Index.

- Tier 2 Watch List and Tier 3 countries listed on the S. State Department’s Trafficking in Persons Report—In this annual report, each country is placed in one of four tiers based on the extent of their governments’ efforts to meet the Trafficking Victim Protection Act’s (TVPA) minimum standards for the elimination of human trafficking.

- Countries where there is a high risk of worker’s rights being violated, as ranked by the International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC)’s Global Rights Index.

High-Risk Sectors/Products

Similarly, customers working in certain sectors may pose a high-risk of forced labor. Financial institutions should use the following lists when assessing this risk category:

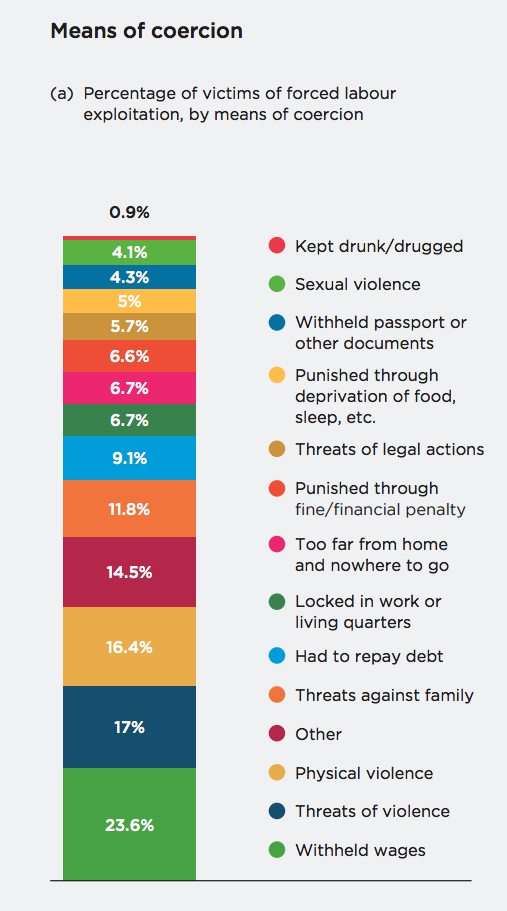

- ILO’s sectoral distribution of victims of forced labour exploitation (see below)—This distribution is based on reported cases of forced labor exploitation.

- S. Department of Labor List of Goods Produced by Child Labor or Forced Labor—Broken down by country, this is a list of the goods that the Department of Labor believes to be produced by child labor or forced labor in violation of international standards—as required under TVPA.

- Verité’s List of Sectors with a Significant Risk of Human Trafficking—This list identifies the 11 sectors most at risk for human trafficking.

High-Risk Products and Services

The risks of money laundering related to forced labor also depends in part on the financial product or services offered. Examples of high-risk products and services includes:

- Electronic banking—Accounts that are opened without face-to-face contact may be a higher risk because it is difficult to verify the customer’s identity and location. The customer may in fact be located in one of the high-risk geographic locations for forced labor or the account might be used by an unknown third party, such as a trafficker, on the laborer’s behalf.

- Funds transfers—Fund transfers may pose a high-risk because it can be difficult to identify the beneficiary. The funds from a forced laborer’s account might be transferred for the benefit of unrelated third parties involved in the victimization of the forced laborer.

- Payroll accounts—Checking accounts used by suppliers to pay their workers present a higher risk as suppliers may also use these accounts to pay traffickers either directly or indirectly.

High-Risk Customers and Entities

Based on occupations, business types, and behavioral indicators, financial institutions can identify which customer accounts are particularly vulnerable to money laundering of forced labor proceeds.

- Worker occupation—The following types of workers are more likely to be victims of forced labor: foreign migrant workers, refugees, low-skilled workers, informal workers, and temporary or seasonal workers.

- Labor-related agencies—These include employment agencies or recruiters, especially if those entities are based overseas or if they are paying wages rather than the employer.

- Unusual in-branch behavior—Labor trafficking victims may have visible bruising or other signs of abuse, poor standards of dress, or poor personal hygiene. They may also avoid cashiers, even when there are no lines at the branch. Other indicators could be that the laborer is accompanied by an employment agent holding all of the laborer’s identification documents, acting as a translator on behalf of the laborer, or demonstrating control over the laborer’s account.

- Adverse media—News articles or media reports about the entity using cheap labor or unfair business practices may be an indication of forced labor.

High-Risk Transactions or Absence of Transactions

The following transactions or missing transactions can be strong indicators of money laundering practices consistent with forced labor.

- High proportion of income withdrawn as cash soon after receipt into the laborer’s account—Sometimes, an employer does not know if their laborers were trafficked. Thus, when an employer pays wages into a worker’s account, the employer might not know that the account is actually controlled by a labor trafficker. Traffickers may withdraw funds without ever transferring the wages to the laborers.

- Multiple employees being paid into a single account—This may additionally indicate that laborers are not receiving their due wages.

- Payments to labor agencies or recruiters—This risk is even higher if these entities are based overseas or if the money transferred comes from the wages of laborers.

- Uniform or suspicious payroll activity—An example is if a payroll account is sending wages where the rate of pay for each pay period is identical and thus there are no changes in wages for overtime, sick leave, vacation, or bonuses, but the employee is working a job where these changes would be expected. Other examples of suspicious payroll activity include if wages are unreasonably low, payroll account does not appear to be paying taxes, or wages transferred back to the payroll account.

- Payment for a non-family member’s passport, visa, or one-way airfare from a high-risk country—Because laborers are likely not to have funds sufficient for these large upfront costs, labor traffickers often arrange the travel and documentation needed for migrant workers and require their victims to repay the debt using their future wages.

- No personal living expenses—Traffickers will use a portion of the wages paid to their victims to provide rent, utilities, food, or gas, but it is unlikely for victims to have control over their own accommodation.

- No evidence tax payments—Because tax payments are typically associated with lawful employment, their absence might indicate forced labor.

High-Risk Similarities Across Customer Accounts

While customers at a high-risk of being engaged in forced labor flows have few unique traits, patterns across several accounts can help financial institutions identify them. There have been at least two instances in which banks were able to conclude forced labor-related transactions had occurred by initially identifying several similarities between different customer accounts because labor exploiters were treating their workers identically.

- Same contact information and employer—Victim accounts may share the same address, phone number, or email address. Labor traffickers want to prevent the financial institution from getting in contact with their victims. They will also often house their victims in substandard housing with as many victims as possible crammed into a small room. In one FATF case study, 15 customers were listed as inhabitants of an address which, as could be seen using Google Street View, would seem to comfortably accommodate only three people.

- Nearly simultaneous transactions—Labor traffickers often conduct transactions, such as income withdrawal, using their victims’ accounts in rapid succession. Once an employer pays wages to a group of exploited workers, a labor trafficker may withdraw a high percentage of that income from the workers’ accounts, often using the same ATM machine around the same time.

Example of High-Risk Factors Combined

In another FATF case study, five customers of a major British bank were living at the same address: four forced labor victims and one trafficker. When opening the accounts, the trafficker served as an interpreter because the applicants could not speak English. The four victims listed the same phone number and two of the victims registered the same email address. Their temporary passports used for identification were all issued in the same month with the same hometown listed. Additionally, the accounts of the four victims had the same patterns of activity; they all received funds from the same employer, followed immediately by ATM withdrawals. The accounts also indicated an absence of living expenses.

Conclusion

The framework of financial institutions’ BSA/AML compliance programs can be adapted to detect illegal profits from forced labor in supply chains by incorporating a forced labor risk assessment. The indicators of forced labor suggest where further due diligence should be conducted, which will in turn help financial institutions identify suspicious activity and report possible violations of law relating to forced labor—as they are required to do under the BSA. If financial institutions help combat forced labor by monitoring high-risk clients and transactions, this could provide significant assistance in the fight to eradicate modern slavery.

Shirley Duquene is a third-year law student at Boston University School of Law pursuing a J.D. with a concentration in Risk Management & Compliance. She received her B.A. in Economics & French from Amherst College. She was a Summer Associate at Ropes & Gray after her first and second years of law school. During the academic year, Shirley was a Staff Editor for the International Law Journal, a student-attorney in the Compliance Policy Clinic and Wrongful Convictions Clinic, served on the E-board of the International Law Society, and will extern for the Corporate Accountability Lab.