Scientist Profile – Professor Joseph McGuire

Unraveling the cognitive mysteries of human decision making

Joseph T. McGuire, Ph.D. – Associate Professor of Psychological & Brain Sciences

The Cognition & Decision Lab, led by Professor Joe McGuire (CNC, CSN), studies the cognitive and neural processes that facilitate human decision making, especially in challenging situations that involve delay, uncertainty, or volatility, or those that seem to demand self-control.

Professor McGuire discussed how aspects like contextual cues or unexpected information can impact the decision-making process, and also shared what he likes to listen to while folding laundry.

How would you describe your research and the goals of your lab?

We study human decision making, especially how people think about the value of choice prospects when there is uncertainty in their environment. One aspect we focus on is how people adapt to different kinds of contexts. For example, we study “adaptive waiting,” or how long someone is willing to wait for something in different situations. As the participant, you have this continuous choice of whether to keep waiting for a reward that will come at some point, though you’re not sure when, or alternatively you can move on to a new opportunity. The situation is a little like a delay of gratification test, except that it’s not always the best decision to continue waiting. If you think about a sit-and-wait predatory animal, like an owl that perches somewhere to forage for prey, well, it’s not necessarily good self-control to wait indefinitely. There’s going to be some point at which it’s no longer worth staying in the same place anymore, and the better bet is to move on.

How do you go about studying adaptive waiting in people?

We have one computerized experiment which involves tokens that increase in value, where people must decide whether to keep waiting an uncertain amount of time for the token to grow in value, or to sell the token for nothing and move on to the next opportunity for a reward (a new token). They play for a limited amount of time and their goal is to maximize their profits. The delays preceding the rewards are partially unpredictable, and we can control the range, distribution, and frequency of the delays. We can create environments where it’s more advantageous or less advantageous to wait longer periods of time. And we find people are quite responsive to those statistics. They’ll learn to persist more in one environment and less in another.

Has anything you’ve learned from this kind of research surprised you?

One question we investigate is how individuals differ in their approach to the situation. We have found that individuals who endorse certain general traits that factor into decision making, like impulsiveness, aren’t necessarily the individuals who most exhibit those traits in their behavior in the lab. We’ll assess traits like patience using scientifically well-validated questionnaires, and our experiments show reliability in that we can ask people to perform the same exercise on separate occasions and they tend to behave in a similar way. And yet, a person’s behavior in our experiments doesn’t always closely match the trait assessment.

The reasons for these discrepancies are still a bit of a mystery. Similar things have been found by other researchers looking at behaviors like risk taking. I think the big-picture answer is that behavioral traits like patience or impulsivity are not just one simple thing. They’re context-dependent, and we need to learn more about the various facets of these traits.

What other aspects of decision-making does your lab study?

We also examine how people interpret a surprise. For instance, if you have a favorite restaurant but today the food is terrible, does that mean the restaurant has changed, or is this merely a one-off outlier that you should ignore? How much do you change your beliefs when something surprising happens? The answer there, again, is that people are sensitive to the context. There are contexts in which a surprise is meaningful, and contexts in which it is not, and people have some ability to infer from experience which kind of situation they’re in.

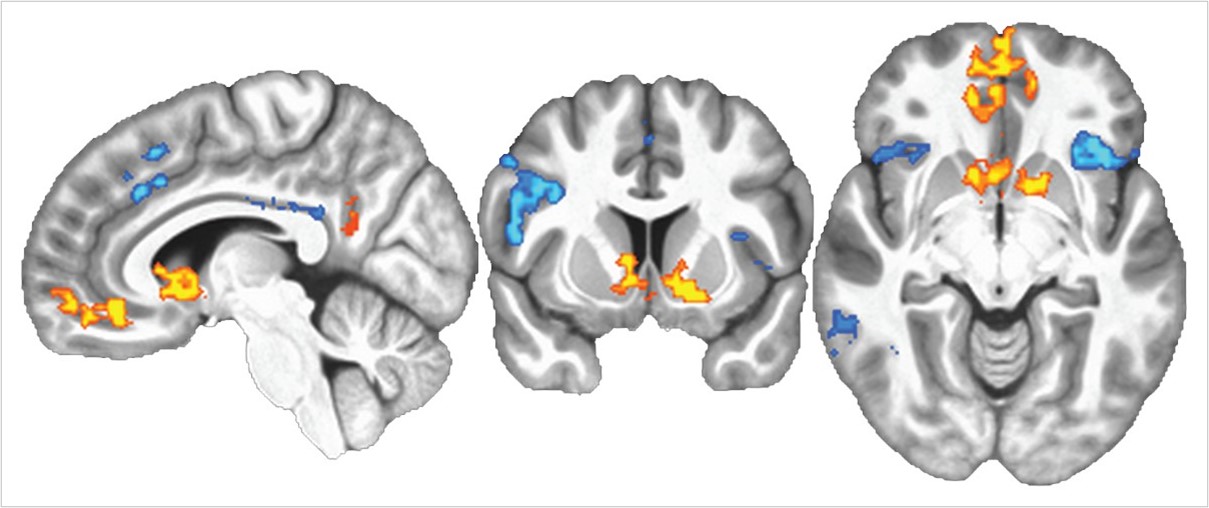

Another thing we do is use functional neuroimaging to look at how people process the value of choice prospects and rewards. We monitor brain activity while people perform decision-making tasks that require assessing value. We know that the brain’s valuation systems seem to overlap with systems involved in other cognitive functions, and we’re working on mapping out those systems in individual brains to get a better understanding of why that is.

Did you always know that you wanted to be a neuroscientist?

Early on in college, my interests were politics and philosophy, but I started taking classes in cognitive psychology and got involved in a lab that studied visual cognition by tracking eye movements—a method I continue to use in my lab to this day. I was struck by how precisely we can measure aspects of behavior that we often don’t even think about. Eye movements are somewhat like breathing in that we can take over control when we want to, but most of the time we move our eyes a few times every second without thinking about it. It still fascinates me that we can measure the information people take in on a millisecond-by-millisecond basis and then study the actions and decisions which are the product of processing all of that information.

What are your hobbies outside the lab?

As a parent, my main hobby these days involves driving kids to sports and activities. In an earlier era of life, I was involved for a while in theatrical sound design and costuming. That work has some similarities to science in that it involves a big group of interesting people all contributing in different ways and working together to accomplish something that hasn’t been done before.

Do you have any favorite books?

This may sound unoriginal, but my current soundtrack for laundry folding is the Lord of the Rings audiobooks.

Interview conducted and edited by Jim Cooney