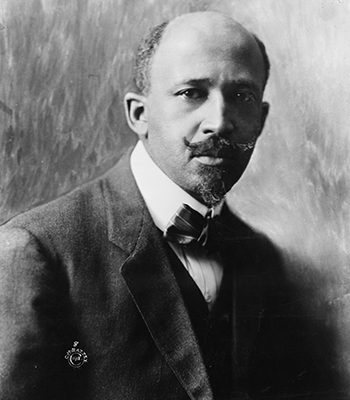

W.E.B. Du Bois Offers Lessons to this Generation of Citizen Activists

Cornell W. Brooks, visiting professor at LAW and STH, reflects on what W.E.B. Du Bois can teach young activists in this Boston Globe op-ed.

During this tumultuous time in America, the youngest Americans are being inspired to become advocates by the most American of tragedies — violence. From the police killing of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Mo., to the neo-Nazi rally in Charlottesville, Va., to last week’s school shooting in Parkland, Fla., younger Americans by the millions have been energized to advocate against persistent police brutality, rising hate crime, and pervasive gun violence. In the wake of the violent deaths of Michael Brown, Tamir Rice, Sandra Bland, and Heather Heyer, and of numerous school shootings, America has witnessed a generationally unprecedented level of activism. On Friday, the 150th anniversary of the birth of a global citizen and son of Great Barrington, W.E.B. Du Bois, offers a few lessons to this generation of citizen activists.

In 1899, the life of the still young scholar Dr. William Edward Burghardt Du Bois was radicalized by a single act of horrific violence. As the first African-American to earn a PhD from Harvard, Du Bois was then a 31-year-old Atlanta University professor. This already distinguished professor was walking to a meeting with the editor of The Atlanta Constitution to discuss the case of Sam Hose, a black laborer who was accused of murdering his white employer and raping his wife. Du Bois was all too aware that African-Americans were often falsely accused of crimes and then, without judge or jury, lynched by mobs. While walking to meet the editor, Du Bois was informed that Sam Hose had already been lynched. Indeed, Du Bois learned that Hose’s knuckles were already being sold as a gruesome souvenir in an Atlanta store.

Du Bois later wrote that the lynching of Hose inspired him to forgo the cool detached logic of an academic for the heated arguments of advocate. Over the course of his 95 years, Du Bois founded the NAACP; launched and led the NAACP’s magazine, The Crisis, served as a progenitor of Pan-Africanism, wrote voluminously against racism and colonialism, raged against lynching and the wanton taking of black lives, and defied racism. These are a few lessons for the citizen activists of this Twitter-age civil rights movement:

First, our heroes and heroines need not demonstrate an uncritical patriotism for their contributions to demand American recognition and gratitude. After having been arrested by the American government at age 82 for being a communist, Du Bois left America and lived out his remaining years in Ghana. He died estranged from the land of his birth, believing the ideal of American equality, in the words of scholar David Levering Lewis, to be a “mirage.” And yet on his deathbed, he sent a telegram of support to attendees of the 1963 March on Washington. The writings of Du Bois both painfully castigated and powerfully inspired America to end Jim Crow segregation in public accommodations with the Civil Rights Act, grant African-Americans fuller access to the franchise through the Voting Rights Act, end lynching, and reexamine the white-washed American history that erased the contributions of African-Americans.