A Chaotic Primary

Gretchen Bennett (’14) on voter protections in Ohio.

A Chaotic Primary

Gretchen Bennett (’14) on voter protections in Ohio.

Gretchen Bennett (’14) had expected Ohio’s primary elections to be smooth, maybe even boring. The voting rights attorney had run voter protection programs for the Democratic Party in the 2016 presidential and 2018 midterm elections, both of which presented real challenges. In Florida in 2018, for example, poorly designed ballots and a lack of campaign coordination led to statewide recount efforts in three key races.

“I would have given odds that Ohio could not out-chaos Florida,” she laughs, “but I would have been wrong.”

The evening of March 16, just hours before voting was scheduled to open, Ohio Governor Mike DeWine and Secretary of State Frank LaRose announced that the primary would be postponed until June 2 in line with public health guidance issued in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. However, state officials asserted that only the Ohio General Assembly had the authority to change the date of an election. The courts got involved, and, lacking other options, Governor DeWine and Director of the Ohio Department of Health Amy Acton closed the polling stations. Confused and with limited information, some poll workers showed up to their stations in the morning.

“It was incredibly chaotic,” Bennett says. “I had 200 poll observers waiting to go into action, and nobody had any idea of what was going on. All kinds of people, with good intentions, were putting out all kinds of misinformation.”

It took a full week to shake out, after which the Ohio State Legislature passed an emergency response bill that mandated absentee, or mail-in, voting, with limited exceptions for in-person voting. The new deadline was April 28, far short of the June date proposed by the governor.

Voter suppression is real. It happens because people aren’t paying attention or aren’t well informed, and it also happens because of an intentional effort to disenfranchise people.

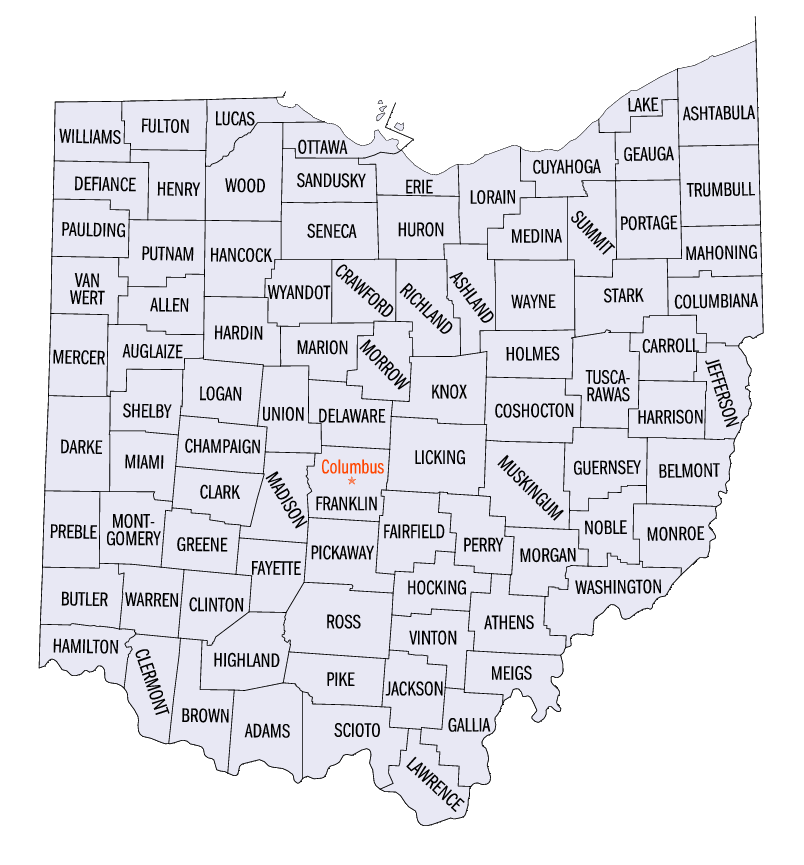

The new deadline sent county election boards scrambling to ramp up messaging and processes for mail-in ballots. In her capacity as voter protection director for the Ohio Democratic Party, Bennett worked with communications teams to craft messages that would get the correct information to voters, help make voters comfortable voting by mail, and help overcome obstacles to do so, like filling out the ballot applications and requesting the right type of ballot. She also dispatched lawyers to each county election board with a list of questions that would help her team understand each board’s processes and request access to public records regarding rejected ballots.

“I was hoping the boards would let us observe in person or would share the information, because it’s public record, when they rejected ballots,” she says. “I wanted to have people chasing those ballots to help cure them.”

Ohio has a 15-year history of no-excuse absentee voting, but the multi-step process to apply for and receive a ballot is more onerous than voting in person. In addition, Bennett notes, some voters don’t trust the absentee ballots. “I guarantee that voters were being disenfranchised,” she says. “I was getting calls and emails from people asking me if this was some kind of a trick. I was offering to help walk them through the process and they were saying that they don’t want to—that they wanted to vote in person.”

All told, voters in Ohio mailed in 1.56 million absentee ballots, 85 percent of the total vote (compared to 8.6 percent of the total vote in the 2016 primaries). While voter turnout was depressed—with 22.65 percent of registered voters casting ballots, compared to 43.66 percent in the 2016 primary—a report from the Stanford–MIT Healthy Elections Project suggests that a noncompetitive presidential field may have also been a factor. All the same, county boards were overwhelmed with mail-in ballots and election count issues persisted.

“It was hard on everyone, including the people on the boards—they’re not the villains, the pandemic is the villain,” she says. “But voter suppression is real. It happens because people aren’t paying attention or aren’t well informed, and it also happens because of an intentional effort to disenfranchise people.”

That’s why Bennett and her team were in Ohio in the first place. In a normal election cycle, she trains poll observers—mostly lawyers and law students—to spot and report issues that may arise as voters cast their ballots. It’s unusual to have a voter protection team on the ground in the primary, but this year, teams were sent to battleground states early in order to “flush away any issues we needed to handle in the primary,” Bennett says. “In Ohio, of course, it turned into the primary that wouldn’t end.

“But I knew there was a reason I was sent here,” she says. “At the end of the day, you want to be somewhere where it matters that you’re there.”

This Series

Also in

Voting in 2020

-

October 31, 2024

Politically Inclined

-

October 20, 2020

The Fight for Fair Elections