Mining for Memoirs

While working as a public defender, Helen Fremont (’82) wrote two acclaimed books about growing up with relatives who hid their Jewish identity after surviving the Holocaust.

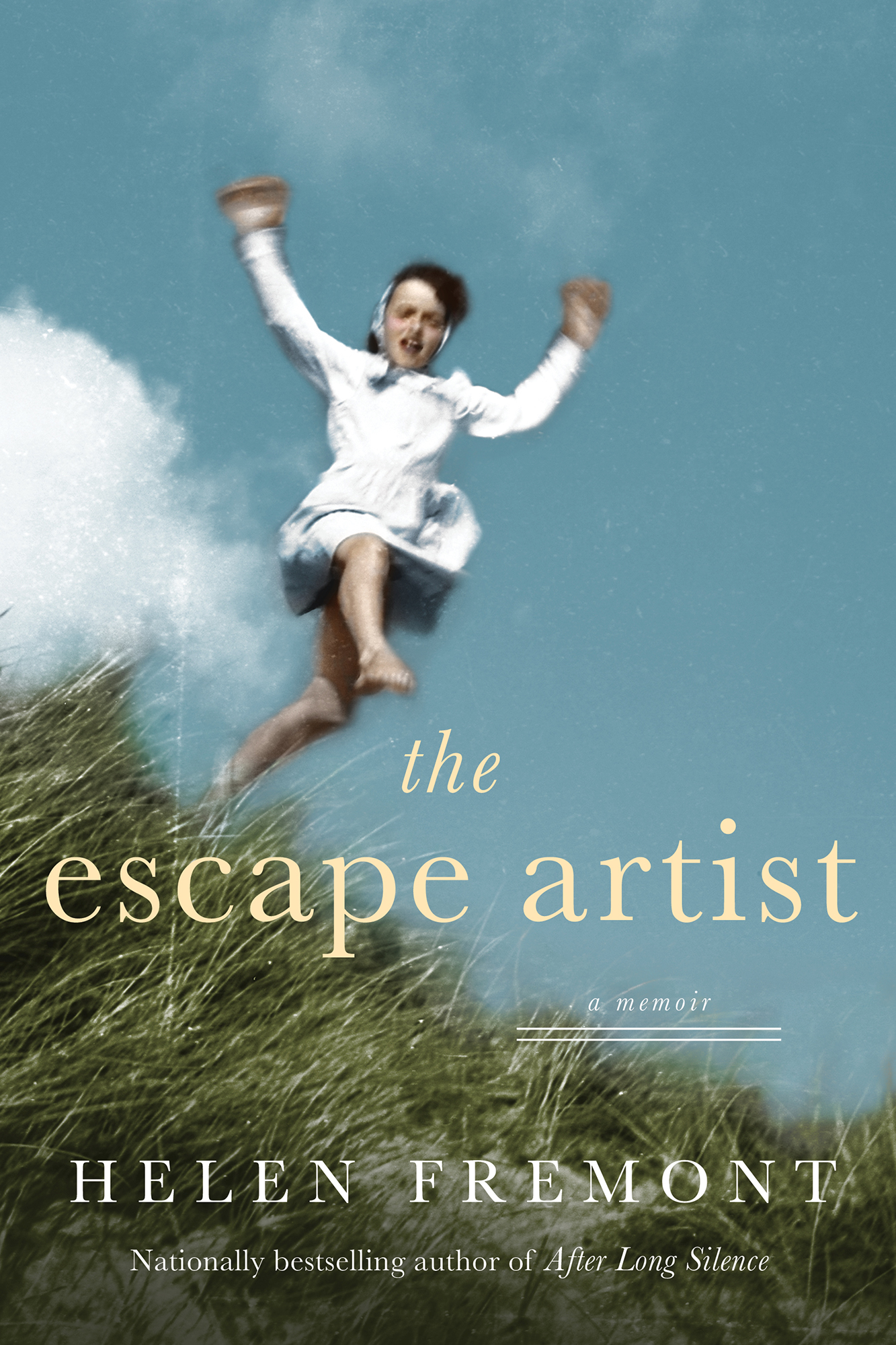

Cover image curtesy of Helen Fremont

Mining for Memoirs

While working as a public defender, Helen Fremont (’82) wrote two acclaimed books about growing up with relatives who hid their Jewish identity after surviving the Holocaust.

When Helen Fremont (’82) first started writing, she was drawn to fictional stories about crime, inspired in part by the people she met and represented as a public defender in Massachusetts.

But her greatest commercial and critical successes have come a lot closer to home. As in, her own home. Fremont is the author of two acclaimed memoirs—the latest published last year—that address her childhood and relationships with her sister and Eastern European–born parents, who hid their Jewish identity from their daughters for decades after surviving the Holocaust and immigrating to the United States.

“I was really, really into crime,” Fremont laughs. “And one of my earliest [writing] teachers said, ‘Frankly, you lack depth.’ She wanted me to work on stuff that was closer to my own story.”

Not long after Fremont started to approach what she knew of her parents’ World War II survival stories—she planned to turn their actual war-torn romance into a novel—she and her sister discovered through conversations with family friends and archival research that their parents were Jewish, not Catholic, as they had been raised to believe. That realization spawned a second career for Fremont, who made time to write when she wasn’t working at Committee for Public Counsel Services, which provides legal representation for people who can’t afford a lawyer in Massachusetts.

“These pages and pages of documents blew everything open,” she explains. “As a writer, in order to make sense of your world, you write.”

Fremont says she always knew she wanted to be a writer but worried her doctor father and teacher mother would not “see that as a ‘real’ career.” She felt she needed an advanced degree and chose Boston University School of Law because it was within driving distance of her family in upstate New York.

“It was inconceivable to our parents that we go anywhere beyond a three-hour drive,” she laughs. “That was verboten.”

Fremont loved learning about the law, especially courses with Professors Wendy Kaplan and the late Lois H. Knight and Dean William Schwartz (DGE’52, LAW’55, GRS’60). She found her passion in the legal profession as a second- and third-year student when she took clinical courses, including a precursor to the Criminal Law Clinic’s Public Defender Program, which allowed her to represent actual clients.

“I loved being able to work with real people who had real problems,” she says. “I could make a difference on a one-on-one basis.”

After graduating in 1982, Fremont taught in Lesotho as a member of the Peace Corps and prosecuted corrupt attorneys as a staff attorney at the Massachusetts Board of Bar Overseers. In 1985, she joined the newly created Committee for Public Counsel Services. She worked as a trial attorney for a few years and then took on a more administrative role overseeing private lawyers who handle cases for the public defender’s office. That’s when she found time to write. She also went back to school, earning her MFA from Warren Wilson College in 1991.

“There were very few emergencies that I had to stay up all night for,” she explains. “So, instead of staying up, I started writing again.”

Fremont, who retired in 2019 after more than three decades in the law, describes the process of learning about her family’s past as “lifesaving.” But ultimately, her decision to publish details about her relatives would have profound consequences.

These pages and pages of documents blew everything open. As a writer, in order to make sense of your world, you write.

Her first book, After Long Silence, was published in 2000, and became a national bestseller; the Boston Globe called it “riveting,” “painfully authentic,” and “a labor of love for the parents she never really knew.” Yet, the book was also a goodbye of sorts. Ultimately, Fremont’s mom could not recover from a feeling that Fremont had betrayed the family by revealing their secret, and, although Fremont’s father kept in touch with her until his death, he added a codicil to his will disinheriting her by treating her as “predeceased.” That event in turn led Fremont to probe her past further in her latest book, The Escape Artist.

“So many people say, ‘How tragic! You lost your family!” she explains. “But I learned that I never had them in the first place. I could have them only as long as I denied my own reality.”

Fremont says her work as a lawyer gave her a unique appreciation for her family’s experiences during World War II.

“The Holocaust could not have happened without a system of laws and legislation specifically against [certain] people,” she says. “It was very much a legal framework. That did remind me that the law is a construction. It’s all about power. Whoever has power creates who is an in-law and who is an outlaw.”

Looking back, Fremont says she also thinks her work as a public defender was a way to honor her father, who was imprisoned in Siberia by the Russians after graduating from medical school.

“In some ways, I felt a real calling to stand between people and the government,” she says. “It’s such a privilege to be able to do that.”

Fremont wants to return to writing fiction, which she describes as “freeing.” But instead, she feels pulled to revisit her own life again. “I hate to say this, but it looks like it’s going to be another memoir,” she laughs. “I keep saying, ‘I should not do this.’ But I think I will.”