A Place for Everyone

Over its 150-year history, BU Law has been home to trailblazers who have made their mark on the law and the world.

A Place for Everyone

Over its 150-year history, BU Law has been home to trailblazers who have made their mark on the law and the world.

In the early 1890s, a man named Owen Young applied and was accepted to Harvard Law School. But when the son of farmers informed the Cambridge institution that he would need to work while earning his law degree, his acceptance was rescinded. Harvard, in that era, was a place for gentlemen. And gentlemen apparently didn’t need jobs.

At Boston University School of Law, Young’s admission came with a personal offer from Assistant Dean Samuel Bennett (1882) to work in the library. BU Law had created the three-year model of legal education, but Young graduated in two and then went on to implement worker-friendly policies as chairman of General Electric, serve five presidents in various capacities, and head up negotiations with Germany on the question of the country’s reparations following World War I.

Fortunately for Young (1896, Hon.’46)—and the world—BU Law was a place for everyone. Since its founding in 1872, the Boston Law School, as it was known at the time, had admitted men—and women—of all races and religious backgrounds. Did Bennett know, when he welcomed Young into the Class of 1896, that his student would go on to make history? Probably not. It’s hard to know how the future will reflect on the present once it becomes the past. It’s more likely that what Bennett and the other founders of BU Law knew was that not admitting certain people—because they were women or because they were poor or because they were Black—would foreclose even the chance that they would go on to make history.

“Boston University School of Law was remarkable because it was much more open” than other law schools at the time, says Professor David J. Seipp, a scholar of legal history and the unofficial historian of BU Law. “We were willing to offer an academically rigorous program to any student of whatever background.”

That openness was a first step toward making the legal profession more diverse, a goal that the school is still working toward today. It also made BU Law a place for trailblazers whose groundbreaking ideas—about race and gender and equality and innovation—continue to be discussed and debated today.

Toward More Just Juries

In 1883, thirteen years before Young graduated from BU Law, Wilford Smith, a Black man from Mississippi, earned his law degree at the school and then opened a thriving practice helping Civil War veterans with their pension applications in his home state.

Smith’s reputation as a leading litigator began with a murder trial in 1900. Representing defendant Seth Carter, he became the third Black attorney to argue before the US Supreme Court and, when the court dismissed the indictment against Carter because no Black people had been selected for the grand jury proceedings, the first to win.

“As a scholar who studies racial and linguistic discrimination in jury selection, I had long known of the Supreme Court case Carter v. Texas, which held that states violate the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment when they exclude people on the basis of race or color from serving as grand jurors,” says Professor Jasmine Gonzales Rose. Although the case was not the first to successfully challenge grand jury discrimination, “it was an important win for jury justice and for diversity and inclusion in the [Supreme Court] bar.”

And Smith wasn’t finished. He would go on to argue another US Supreme Court case, Giles v. Harris, which challenged a new provision of the Alabama Constitution that reduced the number of eligible Black voters in the state from nearly 200,000 to about 3,000. (The work was so sensitive that Smith and Booker T. Washington, who funded the litigation, used code names to correspond about it.) Smith lost Giles in a decision that one law review article described as “controversial and convoluted” and another called the “focal point” for “(anti-)democracy in American constitutional law.”

“He was coming up against a system that was so stacked against him, he could do everything right and still he was not necessarily going to get anywhere,” says Professor Gerald F. Leonard, an expert in constitutional law.

Because jurors are selected in part through voting records, Smith’s Carter and Giles cases were tied up in the same broader effort to protect the rights of people of color.

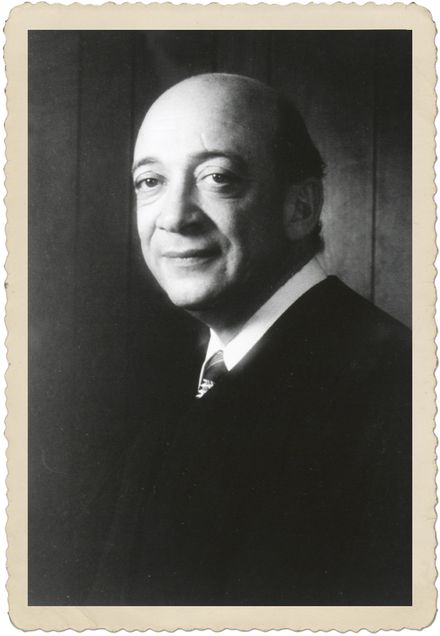

In 1979, another BU Law graduate and longtime professor, Paul J. Liacos (CAS’50, LAW’52, Hon.’96), then a justice on the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court, played his own part in that ongoing effort.

That year, Liacos wrote a groundbreaking opinion, Commonwealth v. Soares, that forbid the “use of peremptory challenges to exclude prospective jurors solely by virtue of their membership in, or affiliation with, particular, defined groupings in the community,” as outlined in the Equal Rights Amendment of the Massachusetts Constitution.

The Soares opinion was later cited by the US Supreme Court in its 1986 Batson v. Kentucky decision. Following Batson, jury cases became more about intentional discrimination against jurors. But, in Soares, Liacos took a broader approach, Leonard says.

“Batson starts with race and then grudgingly moves to gender, and, as far as I know, the [US Supreme] Court has gone no further than that,” Leonard says. “Whereas Liacos from the start says impartiality means a cross-section of the community, and that means a lot of categories.”

In 20 years on the bench, Liacos was reportedly proudest of the Soares decision, which, according to Thomas F. Reilly, then attorney general of Massachusetts who spoke at Liacos’ 2000 memorial, “made a visionary observation about decisionmaking in a democracy”: namely, that true impartiality depends on a diversity of opinions since everyone has some biases.

The ruling “was issued at a time when racial tensions in the city of Boston were high and few public officials had taken an affirmative stand against racism,” Reilly said at the memorial. “In that setting, the Soares decision became a powerful symbol.”

Furthering the Fourteenth Amendment

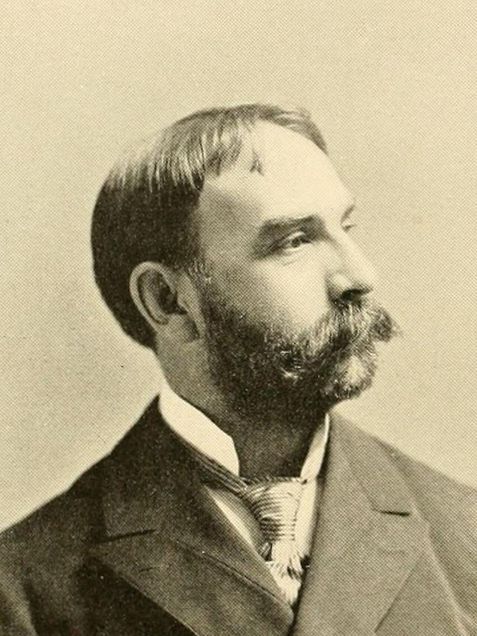

Around the time that Smith argued the Giles case at the US Supreme Court, a BU Law professor and former Massachusetts attorney general named Albert E. Pillsbury was trying to generate support for a federal anti-lynching law. In 1901, a bill he drafted was introduced in the US Senate.

The law was not the first proposed federal legislation to prohibit lynching nor was it the last: when President Biden signed the Emmett Till Anti-Lynching Act earlier this year, the law’s enactment came after more than 200 attempts in more than 120 years. Nevertheless, the bill Pillsbury worked on was the first “thought to have a chance of passing,” Seipp says.

In a 1902 Harvard Law Review article, Pillsbury based his argument for the bill’s passage on the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, which Smith had relied on in his jury and voting rights cases. Just a few years after Pillsbury’s death in 1930, a BU Law alum named Blanche Crozier proposed that the same amendment could—and should—be interpreted to protect another group from discrimination: women.

Crozier, whom Seipp has been researching recently, graduated cum laude in 1933 after serving as an editor of the Boston University Law Review. By November of that year, she was divorced. According to the decree granted to her husband by a probate court in Cambridge, it was Crozier’s habit of typing early in the morning that doomed the marriage.

The “practice…made [the husband] very nervous and constantly agitated,” a newspaper reported.

The practice also made Crozier a harbinger of the women’s rights movement. Between 1933 and 1937, Crozier published a series of articles in the BU Law Review that advanced arguments for women’s equality. One of those, the “Constitutionality of Discrimination Based on Sex” (15 B.U. L. Rev. 723), posited that discrimination against women was just as unconstitutional as discrimination against Black people.

“Race and sex are in every way comparable classes,” Crozier wrote. “And if exclusion in one case is a discrimination implying inferiority, it would seem that it must be in the other also.”

Professor Linda C. McClain, an expert in gender and law, says there is a connecting thread between Crozier’s 1935 article and Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s later description of the Constitution as an “empty cupboard” for women for much of US history.

“There’s a bit of that flavor” in Crozier’s piece, McClain says. “This article is really powerful in pointing out how, from the beginning, some feminists were saying abstract terms like ‘liberty’ and ‘equality’ should apply to us and the court just really didn’t see it.”

Crozier’s article was decades ahead of its time, but her “incisive thinking…was not wasted; only delayed,” according to Pauli Murray, another pathbreaking person with ties to BU Law, whose work served as a sort of bridge between Crozier and Ginsburg.

In 1965, Murray cowrote an article about sex discrimination and its relationship to racism that cited Crozier’s work. Murray would in turn be credited by Ginsburg when the future US Supreme Court justice won her 1971 case, Reed v. Reed, which finally established that discrimination against women violated the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, just as Crozier had argued four decades earlier.

Murray, who self-identified as a “he/she personality” in letters to family and for whom the Pauli Murray Center for History and Social Justice now uses he/they pronouns for descriptions of Murray’s early life and she/her for later years, was as forward-thinking as Crozier in multiple contexts. As a student at Howard University School of Law, Murray wrote a paper arguing that the “separate” part of the US Supreme Court’s “separate but equal” doctrine from Plessy v. Ferguson was unconstitutional; that argument later became the basis for Brown v. Board of Education. Murray was a close friend of Eleanor Roosevelt, the author of a book on segregation laws that Thurgood Marshall referred to as “the Bible,” a cofounder of the National Organization for Women, and, before her death in 1985, the first Black woman to be ordained an Episcopalian priest.

McClain, who teaches Murray’s work in her classes on feminist jurisprudence and gender equality law, says Murray was “there at so many pivotal moments in history.”

Murray was also at BU Law. In 1972, she taught a course on civil rights.

“She was quiet but dynamic,” says Professor Emerita Frances H. Miller (’65), who was a lecturer at the time. “You knew you were talking to someone who knew what she was talking about.”

Nevertheless, Murray, like the handful of other women on the faculty at BU Law at the time, was relegated to the “ladies’ section” on the second floor of the tower, according to Miller. Although BU Law had admitted women since its founding a century earlier, there was only one woman on the full-time faculty in those years: Professor Tamar Frankel.

Murray wasn’t on campus regularly—she was also a full-time professor at Brandeis University—and Miller wasn’t aware then of the extent of Murray’s contributions to the civil and women’s rights movements. But it is likely that another BU Law graduate, Clarence B. Jones (’59), was.

Jones was working in Los Angeles as an entertainment lawyer when Martin Luther King, Jr. (GRS’55, Hon.’59) visited him at home to ask him to join his legal team. Jones was reluctant, but King was determined and applied a full-court press. Soon, Jones became one of the civil rights leader’s closest advisors. He helped to get King’s “Letter from Birmingham Jail” to the public and to organize the March on Washington where King delivered his iconic “I Have a Dream” speech, which Jones helped write and had copyrighted.

Murray also played a role in the March on Washington. As described in the book The Firebrand and the First Lady, they—and others—protested the marginalization of women in the event.

The Civil Rights Movement has since expanded to include advocacy for other historically marginalized groups—including the LGBTQIA+ community that now claims Murray as its own—and the Fourteenth Amendment that Pillsbury, Crozier, and Murray wielded has been a popular and powerful tool in those efforts.

A Politician Brings the Constitution to Life

Barbara Jordan (LAW’59, Hon.’69) was a product of the Civil Rights Movement—she won her 1966 election to the Texas Senate in part because of redistricting required under the 1965 Voting Rights Act.

When she was elected to the US House of Representatives in 1972, Jordan was the first Black congresswoman from a southern state and one of the first two Black representatives in the post-Reconstruction era.

“I’ll be one of 435,” she said at the time, “but the 434 will know I’m there.”

Jordan advocated for immigrants’ rights, public schools, and legal aid, among other causes, but she came to national prominence during the impeachment of President Nixon. On the question of whether the Constitution applied to Nixon’s conduct, Jordan—who kept a copy of the Constitution in her purse—offered a personal and historical account during a House Judiciary Committee hearing.

“…I was not included in that ‘We the people’… but through the process of amendment, interpretation, and court decision, I have finally been included…,” she said. “…My faith in the Constitution is whole; it is complete; it is total. And I am not going to sit here and be an idle spectator to the diminution, the subversion, the destruction, of the Constitution.…If the impeachment provision in the Constitution of the United States will not reach the offenses charged here, then perhaps that 18th-century Constitution should be abandoned to a 20th-century paper shredder.”

Her message was so powerful that one Houston man paid to display “THANK YOU, BARBARA JORDAN, FOR EXPLAINING THE CONSTITUTION TO US” on 25 billboards.

Jordan went on to deliver a keynote address at the 1976 Democratic National Convention in New York. She received a three-minute standing ovation before speaking for 25 minutes in remarks that called for unity but also acknowledged the Democratic Party’s past mistakes.

Professor Jack M. Beermann, who studies civil rights litigation, was a newly eligible voter at the time and watched Jordan’s speech.

“I remember being just blown away by how inspiring she was,” he recalls, noting that Jordan viewed the Constitution as an aspirational document. “That’s what Barbara Jordan did for her entire career: embark on the hard work of realizing the ideals of the US Constitution for all people.”

Jordan held Nixon to account for abusing the power of the presidency; a quarter-century later, Philip S. Beck (’76) made a name for himself in part as a member of the legal team that paved the way for George W. Bush to assume that office.

Beck, who served as editor of the BU Law Review, is a well-known trial attorney who spent 16 years at Kirkland & Ellis before forming his current firm, Bartlit Beck, in 1993. He was at home for Thanksgiving when his partner called him to tell him they had been hired to assist Bush in his ultimately successful effort to prevent a recount in Florida of disputed ballots in the 2000 election. The team ultimately won a ruling from the US Supreme Court that a recount would be unconstitutional.

Beck later downplayed the significance of his role—“I was briefly a minor celebrity for that small segment of the population that cares about politics,” he said in a 2006 interview. But the public’s—and Vice President Al Gore’s—acceptance of the outcome in the case, which is still controversial, has been held up as an example of the importance of the rule of law in a democracy.

The Power of a Law Degree

At GE, Owen Young was a pioneer of what was known at the time as “welfare capitalism.” He implemented a series of programs designed to improve the lives of his employees and their families, including pensions, profit sharing, mortgage loans, and life and unemployment insurance. He also advocated for what he called a “cultural wage.”

“No man is free until want is removed from his door and until his intellect may be developed to take advantage of all the opportunities which may be available and are guaranteed to him in a free country,” he said in the 1920s.

Within two years of his chairmanship, workers at GE were making 25 percent more than they had previously.

“Today, he would be right in the midst of the progressive wing of the Democratic Party,” says Professor David I. Walker, an expert in business and corporate law. “He would probably be dismayed to see how little progress we have made on a social safety net.”

What stands out most about Young is his “ability to move seamlessly” between roles—at law firms, at major corporations, in government—while always prioritizing the public interest, Walker says.

But, of course, when you open your doors to everyone—as BU Law did at its founding, as a democracy does in every day of its existence—you equip people to act on their best and worst intentions.

Albert Pillsbury was a longtime ally of the Black Civil Rights Movement—he was a founding member of the NAACP and a friend of W.E.B. Du Bois—but when it came to equality, he drew the line at women. Pillsbury campaigned against women’s suffrage and, upon his death, left significant contributions to several schools to “create and develop sound public opinion against impairment of the family by taking women out of the home.”

A law degree is a powerful tool. Young seemed to recognize the danger of that power even as he set out upon his own career.

In 1896, speaking as class orator, Young told his fellow graduates their duty was “to use, not to abuse, the law.” And fulfilling that duty is what so many BU Law students, alumni, and faculty have tried to do for 150 years.

Because history repeats itself, all of the efforts described here—on behalf of women and workers and people of color and democracy itself—continue to this day. It can be overwhelming to contemplate how much history must still be endured before, as Crozier wrote in 1935, “the privileges which citizens enjoy might be expected to increase.”

But Smith and Crozier and Murray and Jones did not just endure. Instead, in even the most trying of times, they engaged. Smith and Jones left successful private practices to devote their considerable legal talents to the Civil Rights Movement. Crozier had two daughters and published a novel before she went to BU Law, where she typed her way to a divorce as she developed one of the most influential legal arguments of the 20th century. In 1940, Murray became an advocate for Odell Waller, a Black man sentenced to die by an all-white jury for the shooting death of a white man.

“Let each day count for something,” Murray wrote in one letter to Waller. “You have no time to get blue and down. You have a stake in democracy also, and you must try to find the part you are playing.”

Murray took their own advice. Until then, they had contemplated becoming a writer, but, as they wrote to a friend, “the exigencies of the period have driven me into social action.”

A few months later, they went to law school.

FEATURED IN