A Support System for Black Women Law Professors

The 16th Annual Lutie A. Lytle Black Women Law Faculty Workshop, founded by BU Law Dean Onwuachi-Willig, offers inspiration and support to scholars and practitioners.

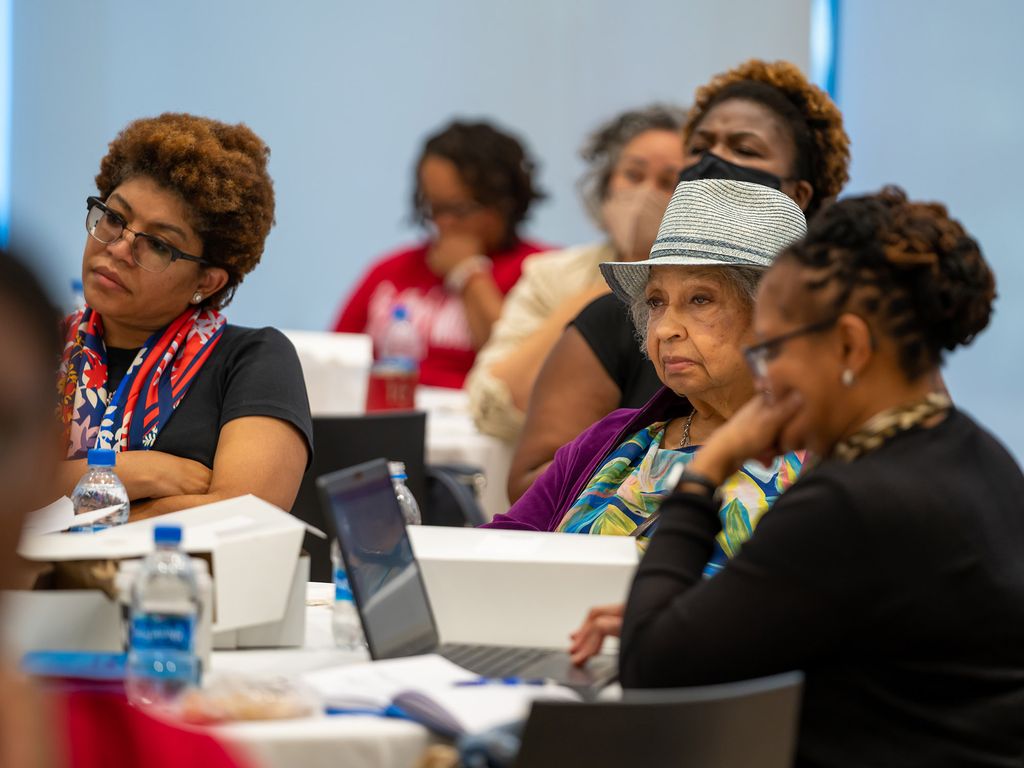

Photos by Luguzy Atkins

A Support System for Black Women Law Professors

The 16th Annual Lutie A. Lytle Black Women Law Faculty Workshop, founded by BU Law Dean Onwuachi-Willig, offers inspiration and support to scholars and practitioners.

When Angela Onwuachi-Willig started the Lutie A. Lytle Black Women Law Faculty Writing Workshop, more than a decade before becoming dean of Boston University School of Law, the goal was to increase diversity and improve tenure rates among Black women in the legal academy. Twenty-five women attended the inaugural event in 2007.

In June, when Onwuachi-Willig hosted the 16th annual workshop at BU Law, more than that number of “Lutie sisters” were serving as deans of their institutions. Of the 135 attendees, 28 hold the top position at their law school.

“We do have real results,” Onwuachi-Willig says.

The workshop, named for a daughter of formerly enslaved parents who became one of the world’s first Black woman law professors, offers much more than that, according to participants. Since its founding, the Lytle Workshop has carefully supported current and aspiring Black women law faculty by organizing constructive critiques of developing scholarship, providing programming designed to improve people’s chances for hiring on the academic market, and offering guidance and mentorship in a welcoming community.

University of Illinois Chicago School of Law Dean Nicky Boothe says she was “blown away” by her first Lytle Workshop in 2009. At the time, she was a professor at the College of Law at Florida A&M, a historically Black university.

“Even though I was used to seeing a diverse crowd of faculty members, there was just something about this collective of beautiful Black women, all of the same mind, all about success—and not just in academia but in their lives,” she says. “It really struck a chord with me.”

University of Alabama School of Law Assistant Professor Daiquiri Steele first heard about the Lytle Workshop at an American Bar Association conference in 2016 from a then-stranger—Lutie sister and University of Kansas School of Law Professor Jamila Jefferson-Jones. Steele had just accepted a non-tenure track position at Alabama and was so intrigued by the idea of the workshop that she took a week off from her job as a civil rights attorney to attend.

“I’ve not missed a year since,” she laughs.

When she decided to pursue a tenure-track position, Steele says, the Lytle Workshop network was instrumental in that process. Some people have personal connections who can help them advance in the academic world; “for those who don’t, we have Lutie,” she says.

“Lutie’s the reason I’ve been able to be successful in publishing, period,” Steele adds. “It was the reason I was able to be successful with respect to the job market.”

Lutie sisters have made a name for themselves in all facets of the law and the legal academy. Howard University School of Law Dean Danielle Holley-Walker was on a short list of potential US Supreme Court nominees for the seat of Justice Stephen Breyer that eventually went to Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson. University of Denver Sturm College of Law Professor Catherine E. Smith’s amicus brief arguing that laws against marriage between same-sex couples unconstitutionally harmed children—workshopped at a Lytle conference—was cited by the US Supreme Court majority in the Obergefell decision. And, at this year’s workshop, Holley-Walker and Lutie sister and Elon University School of Law Professor Tiffany D. Atkins shared a draft amicus brief they each worked on that was later filed in the US Supreme Court on behalf of Black women law professors in support of Harvard University and the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill in cases challenging the use of race as a factor in admissions.

One reason Onwuachi-Willig and others started the Lytle Workshop in 2007 was the dismal state of diversity in the legal academy. According to reports from the Association of American Law Schools (AALS) at around that time, men outnumbered women in almost every racial or ethnic group (among whites, there were twice as many men as women) and only seven percent of the total number of law faculty in the nation were women of color.

“The voices of Black women matter—they have helped make our country better,” Onwuachi-Willig says. “This community creates a space and a support system for the people who are doing that important work to feel nurtured and backed.”

A recent report from AALS shows improvements, at least among law school deans. Between 2005 and 2020, the share of women deans increased from 18 percent to 41 percent and the share of deans of color increased from 13 percent to 31 percent.

Noting the number of Black women deans, Onwuachi-Willig says, “That is in part due to Lutie Lytle.”

Those numbers are crucial, she says, “in terms of making a difference in people’s lives, in the lives of students, in the academy. People bringing in their own experiences through their scholarship broadens all kinds of things.”

The Lytle Workshop, which provides scholarships for people who otherwise cannot afford to attend, is also a source of inspiration for its members.

“The support and encouragement you get is unparalleled,” says Steele. “There’s nothing like having a group of similarly situated women who have been where you are and where you are trying to go, truly have your best interests at heart.”

Onwuachi-Willig embodies that spirit, Boothe notes.

“She is nothing short of amazing and so unassuming in her amazingness,” she says. “She was going through the tenure process when she decided to start [the Lytle Workshop]. Most times when you’re going through tenure, you’re not thinking about anyone else. For her to have that foresight, to know there was strength in numbers, that speaks to who she is.”