Critical to Our Future

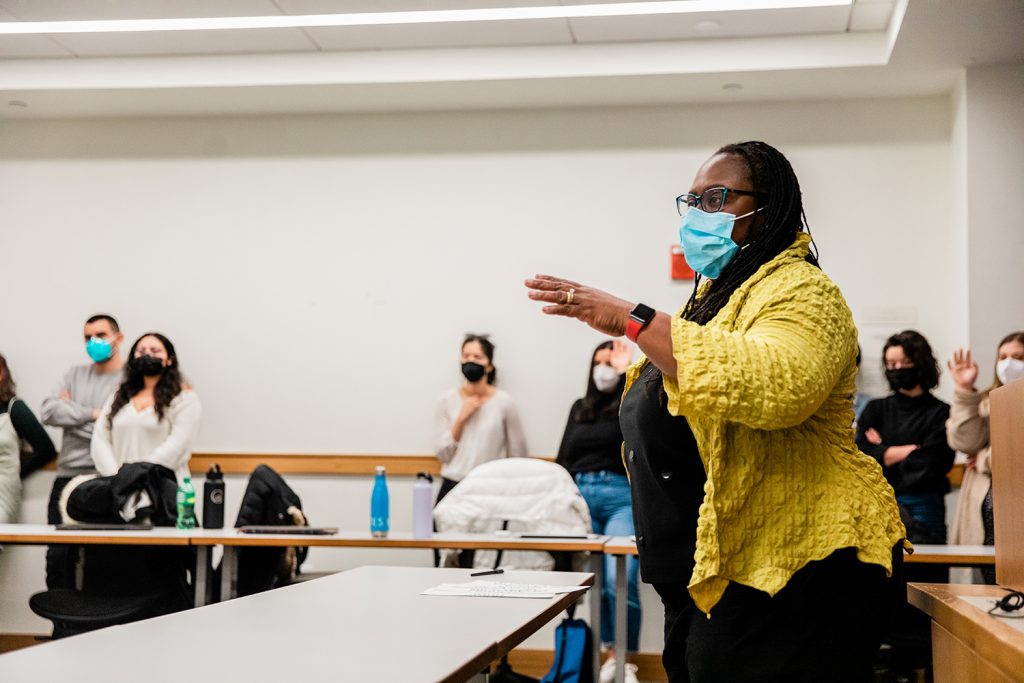

Dean Onwuachi-Willig returns to the classroom for the first time since joining BU Law.

Photo by Conor Doherty

Critical to Our Future

Dean Onwuachi-Willig returns to the classroom for the first time since joining BU Law

For the first time since becoming dean of BU Law in 2018, this spring I once again stood in front of a classroom, teaching a course to 15 eager students. I admit I felt a little shaky on my first day, but teaching is like riding a bicycle—the familiar rhythms come back quickly.

And yet, the world has changed in fundamental ways since I last taught, and the topic of the course—a colloquium on Critical Race Theory (CRT)—has become a cornerstone of the culture wars by some in our society who either misunderstand or mischaracterize its purpose.

Prior to September 2020, CRT, which is taught by a relatively small number of legal academics, was virtually unknown to the majority of US residents. By the following June, it had become one of the most widely searched terms on Google in the country. CRT has received considerable negative press in the last two years, as politicians like Florida Governor Ron DeSantis label it “state-sanctioned racism,” falsely claiming that it teaches kids to hate our country, and as local school boards debate banning it from the K–12 curriculum, where it is not taught.

A color-blind approach to law cannot resolve racial inequities and problems any more than a cancer-blind approach to medicine can cure cancer.

I consider this backlash to be both good news and bad news. Bad news, because it disturbs me to see politicians succeeding in turning people against CRT when it is clear that neither they nor their supporters understand what CRT truly is. Good news, because these scare tactics are a sign that the protests of summer 2020 produced policy reforms and court verdicts that few people would have considered possible just a few years ago.

This burgeoning awareness of CRT, however ill-informed, causes students to approach the colloquium quite differently than when I last taught the subject at Berkeley Law in 2017. Although I still focused our discussions on the fundamental tenets of CRT, today’s students often reflected on the political rhetoric and public debate about CRT as well.

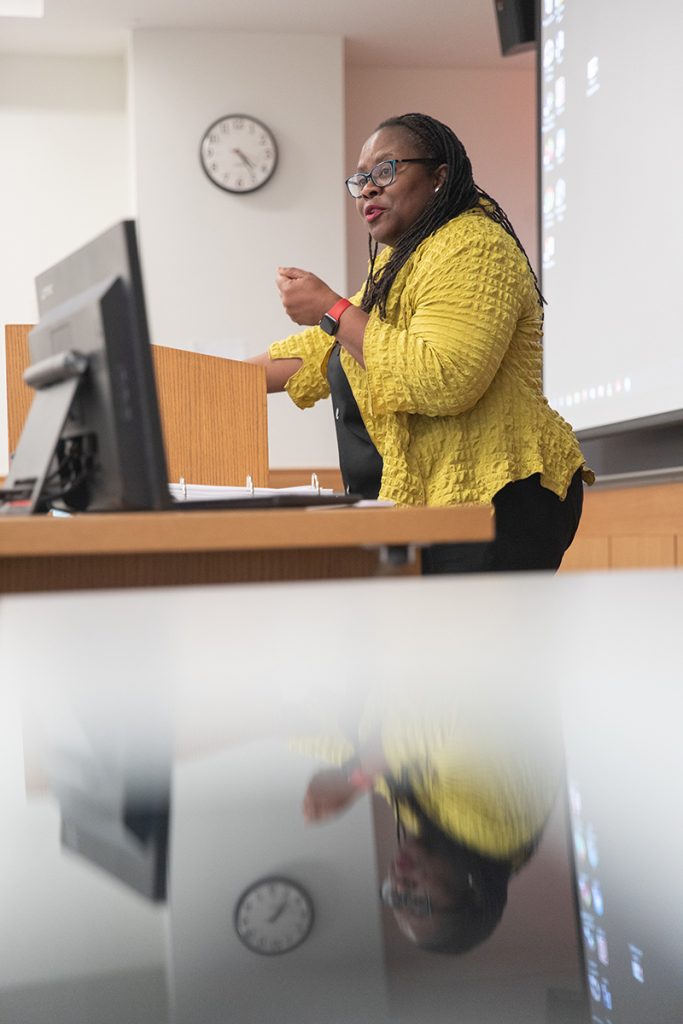

Angela Onwuachi-Willig speaks at the front of the class. Photo by Conor Doherty.

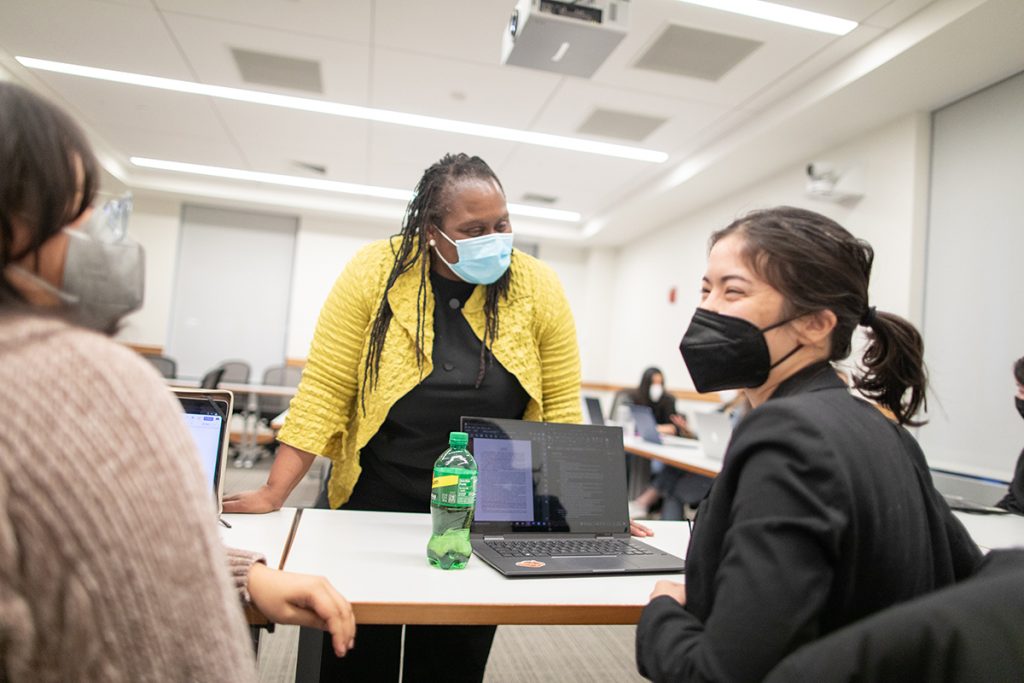

Students engage in discussion as Dean Onwuachi-Willig looks on. Photo by Conor Doherty.

Earlier this year, Brittany Murphree, a white student at the University of Mississippi School of Law who self-identifies as a conservative Republican, enrolled in Professor Yvette Butler’s CRT course despite resistance from her family and friends. After only a few class sessions, Murphree made national news when she penned a letter to the 27 members of the Mississippi House Education Committee arguing against a bill aimed at banning schools and universities from discussing CRT. She wrote:

“To date, this course has been the most impactful and enlightening course I have taken throughout my entire undergraduate career and graduate education at the State of Mississippi’s flagship university. The prohibition of courses and teachings such as these is taking away the opportunity for people from every background and race to come together and discuss very important topics which would otherwise go undiscussed. I believe this bill not only undermines the values of the hospitality state but declares that Mississippians are structured in hate and rooted in a great deal of ignorance.”

The prohibition of courses and teachings such as [Critical Race Theory] is taking away the opportunity for people from every background and race to come together and discuss very important topics which would otherwise go undiscussed.

Brittany Murphree is a clear example of why I believe it is valuable for all law students to consider CRT. I want them to think about the ways in which the law might reify racial disparities, even when racism is not obvious in the language of the law. Racial bias can often be present in our legal doctrines because their authors were primarily white judges who were writing from their own experiences and then wrongfully assuming that those experiences encompass the realities of all people. I also think it is important for students to understand how race is socially constructed and why a color-blind approach to law cannot resolve racial inequities and problems any more than a cancer-blind approach to medicine can cure cancer. Perhaps most importantly, I teach CRT to help students see and understand the law, and the world, through a different lens.

During the semester, I watched students grapple with whether and how to share racial issues and problems that we are often too scared to confront and discuss in our society. I saw students listen to and learn from one another. I saw them relate to peers in ways they never had before. I hope the lesson they learned and will take into their future workplaces is that we can and should talk about and act on issues of race and racism.

This kind of engagement is so critical that I worked with Deans Erwin Chemerinsky and Camille Nelson and Professor Kimberly Norwood in urging law school deans from around the country to advocate that the American Bar Association require every law school to provide education around bias, cultural competence, and antiracism, new standards the ABA enacted in February. Requiring such training is not about taking away students’ or even faculty’s choices, but rather about taking away the fear that often prevents students from enrolling in these types of classes, that can and will better prepare them to provide competent representation for a diverse group of clients—which can only in turn result in a more just future for the legal profession and our society.