License to Stream

New technologies have made making and enjoying music easier than ever, but they're running into the same old complications of copyright law that have always rocked the industry.

Illustration by Aldo Crusher

License to Stream

New technologies have made making and enjoying music easier than ever, but they’re running into the same old complications of copyright law that have always rocked the industry.

When a client trying to launch a new music streaming service wrote to Boston University School of Law student Ross Chapman (’22) with a series of questions about how she could acquire the rights to the songs she wanted to offer on her platform—and how much she would have to pay to do so—Chapman responded in two ways.

First, he and a fellow student offered short answers, designed to provide the requested information simply and succinctly. Then, they offered long answers, in an effort to explain how they arrived at the short ones.

Most of the questions had long answers, and it’s no wonder.

Music copyright law is complicated; the 2018 Music Modernization Act (MMA)—which included a provision that took effect starting in 2021 that changes the way music streaming services acquire certain licenses—almost doubled the number of words in the 1976 Copyright Act it amended.

“If you’re not a lawyer, you would expect that there would be very simple answers for basic questions such as ‘How much do we need to pay to use this music?’” Chapman says. “But what that required was a very close reading of the federal regulations that have come about as a result of the Music Modernization Act.”

Chapman’s client wasn’t real—her questions came as part of an assignment for a new transactional simulation course designed by Samuel L. Taylor (’12) called IP Counsel for New Music Streaming Service. But there’s nothing fictional about the complexities behind the music streaming business.

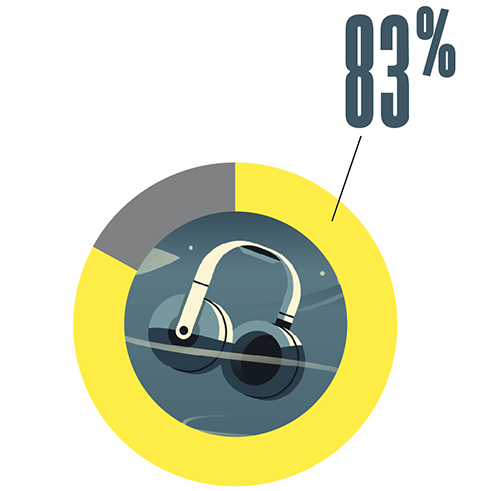

In 2020, streaming services in the United States brought in $10.1 billion in revenue—83 percent of the music industry’s total. But they also must pay to license the rights to every song they offer on their platforms. They pay to reproduce and distribute musical compositions, to publicly perform musical compositions, to reproduce or distribute sound recordings of musical compositions, and to publicly perform sound recordings. They pay licensing fees to songwriters and publishers, record labels, and performing rights organizations, among others. And that’s just scratching the surface. The copyright regime for music streaming is so complicated and so uncertain that Spotify identified several licensing scenarios as risks when it released its financial results for the second quarter of 2021.

“I love to start off my course by saying, ‘Music licensing is a shit show,’” laughs Taylor, who serves as assistant director of the BU/MIT Startup Law Clinic. “That’s the baseline, and then we go from there.”

Taylor’s class couldn’t be timelier. In 2020, the Copyright Royalty Board increased the rates streaming services would be required to pay to songwriters and publishers for the use of their musical works. The services—Spotify, Amazon, Google, and Pandora—then challenged those new rates in court and won on the grounds that they hadn’t been given proper notice of the increase. And early in 2021, musicians organized protests at more than 30 Spotify offices around the world, demanding increased transparency in the company’s business model and more money per stream.

Battles over royalties are nothing new in the music industry, and neither is the centuries-old balancing act behind them. Article one, section eight of the US Constitution gives Congress the power “to promote the progress of science and useful arts, by securing for limited times to authors and inventors the exclusive right to their respective writings and discoveries.”

“Copyright law is not just for copyright owners,” says BU Law Professor Jessica Silbey, whose work explores intellectual property in the digital age. “Copyright law is a public good, meant to promote progress. That’s what copyright law is supposed to do. When we debate, under the MMA, who gets which money, we’re losing sight of what copyright law is for.”

The Napster Effect

The MMA passed the US House of Representatives and Senate unanimously in 2018, a testament to the widely acknowledged reality that copyright law had failed to keep up with changes in the way people listen to and share music.

An early—and unwelcome to the traditional music industry—harbinger of that change was Napster, a peer-to-peer file sharing service that allowed people to play and exchange music for free online. Beloved by college students DJing parties from their dorm-room desktops, Napster was shut down by a federal judge in 2000 for copyright infringement. But the cat was out of the bag. People had grown accustomed to the idea that they shouldn’t have to buy a CD to have access to their favorite music.

Copyright law is a public good, meant to promote progress. That’s what copyright law is supposed to do. When we debate, under the MMA, who gets which money, we’re losing sight of what copyright law is for.

Silbey says “breakthrough innovations” like Napster should be celebrated.

“There’s something about pushing the envelope and challenging the rules that creates this new marketplace of opportunity that made music much more accessible to us today,” she says. “Whatever we think about piracy or hackers, we should be less judge-y about it. There’s an ecosystem for challenging existing rules and celebrating loopholes.”

In other words, early innovators—even when they’re bending or breaking the law—drive the progress component of copyright law.

Services like Spotify emerged to legally fill the void left by Napster but found it cumbersome to negotiate the panoply of licenses required to offer music to their paying and nonpaying subscribers. That’s where the MMA comes in. One of the law’s central features was to streamline that process, making it easier for providers to acquire rights and for rights holders to get paid.

Before the MMA, “there were a lot of gaps in the law,” says Jay Fialkov (’81), deputy general counsel for public media powerhouse GBH in Boston and a professor at Berklee College of Music, where he teaches classes about legal aspects of the music business. Those gaps led to litigation between streaming services and copyright holders, with the latter arguing that the services were building businesses worth many billions of dollars based on their musical works without acquiring the rights to do so. It was a case of the “wine bottle becoming more valuable than the wine,” Fialkov says. “One of the goals of the MMA was to clean that mess up.”

The MMA created a separate entity—the Mechanical Licensing Collective—which collects a blanket licensing fee from streaming services and then pays royalties out to songwriters and publishers, balancing the competing interests spelled out in the Constitution.

“That compromise—to keep the legacy industries happy but also facilitate new industries—is classic copyright legislation,” Silbey says. “The impulse is absolutely praiseworthy. But it’s super messy.”

Money, Money, Money

Even as the MMA created a new process to facilitate a new technology, the law could not settle a very old complaint in the music industry, which is that people aren’t being paid enough for their work, whatever that work is.

“Songwriters have historically been the winners in copyright,” Silbey says, pointing to the compulsory licenses required for anyone who wants to record someone else’s song. “They’re complaining now because performing artists and sound recording artists are going to get more of the pie.”

The songwriters are fighting it out with streaming platforms before the Copyright Royalty Board. Meanwhile, the protestors outside Spotify’s offices in 2021 were demonstrating against the company’s so-called pro-rata business model, which pays performers based on their percent of total streams across the platform, a system in which the most popular singers and groups make most of the money. Spotify currently pays out between $.003 and $.005 per stream, meaning it would take more than 250 streams to even clear a dollar. That money is then divided among publishers, distributors, and artists. Protestors argue that a user-centric model, like the one French company Deezer uses to pay artists based on their share of each subscriber’s streams, would be fairer.

“The issue that’s potentially becoming the most prominent is that even if you accept [the MMA] as a thoughtful solution that rightfully balances the interests of copyright holders and the public, there are still people who say, ‘It’s not paying enough,’” Fialkov says.

Of course, streaming is just one, relatively new source of revenue for artists. Cordaro Rodriguez (’12), a classmate of Taylor’s who is a member of the musical quartet Sons of Serendip, says that in 2020, his group had 1.3 million streams on Spotify. More than 350,000 people in 91 different countries listened to their music.

But Rodriguez says his group, which was a finalist on America’s Got Talent in the show’s ninth season, doesn’t look at streaming as its “primary vehicle of income.” Instead, most of the group’s revenues come from touring. (Sons of Serendip has opened for John Legend and Jay Leno, among other bookings.) The next biggest chunk is CD sales, and streaming royalties—from Spotify, YouTube, Apple Music, and other platforms—make up the remainder.

Rather than striving to write singles that will generate streams on Spotify, Sons of Serendip is focused on making music that “expresses our artistic creativity,” Rodriguez says. To make up for times when touring is harder to arrange—because of the pandemic, for instance, but also as members start families and need to stay closer to home—the musicians are pursuing television and film deals as well (audiovisual works that incorporate musical compositions or sound recordings are governed by an entirely different set of licenses).

“Streaming isn’t necessarily our main goal,” Rodriguez says. “That money just trickles in without us having to do anything.”

Streaming royalties weren’t even on the table when Fialkov was negotiating contracts for his music clients—including Phish and “Marky Mark” Wahlberg—when he had a private law practice in the 1980s and 1990s.

“That money didn’t even exist when I represented recording artists and record labels,” Fialkov laughs. “Even if the amounts being paid to rights holders aren’t what they really should be, they’re starting to add up.”

Taylor agrees.

“Right now, if they buy the right equipment, anyone can record music in their bedroom, and it can sound professional,” he says. “Twenty years ago, to have a proper recording would have cost thousands of dollars in studio time and you probably would have needed to be signed to a label for distribution. That’s all irrelevant now. You don’t have to spend a lot per month to get on Spotify and blow up that way.”

The Short Answer

Chapman did well in Taylor’s class and on the assignment where he had to explain how much the fictional streaming service owner might have to pay in licensing fees to various rights holders.

But, perhaps more importantly, he also says he has a better sense of the logic behind the concepts he learned about from Taylor and others, including Silbey, with whom he studied copyright law and for whom he later served as a teaching assistant.

Copyright law, says Chapman, a trombone player who majored in music as an undergraduate student at Columbia, doesn’t always make sense “from a musician’s perspective.”

“It makes more sense as a compromise,” he says. “There’s only so much money to go around to all of the constituents. If we want a society with so much music available to us, compromises have to be made.”