The Politicians

Five alumni who have made their careers in service to the public.

Illustration by the Project Twins

The Politicians

Five alumni who have made their careers in service to the public.

Since its founding in 1872, Boston University School of Law has taken considerable pride in its faculty, staff, students, and alumni. It was with our community in mind that we set out to create 150/150, a commemorative book featuring 150 profiles of people, places, and events that have shaped the school and the world.

Throughout the school’s anniversary year, The Record is publishing a selection of the profiles that appear in the book. We present here the five leaders who served as a voice of the people, often going against the grain when it wasn’t the easiest path forward.

Learn more about BU Law’s 150th anniversary book

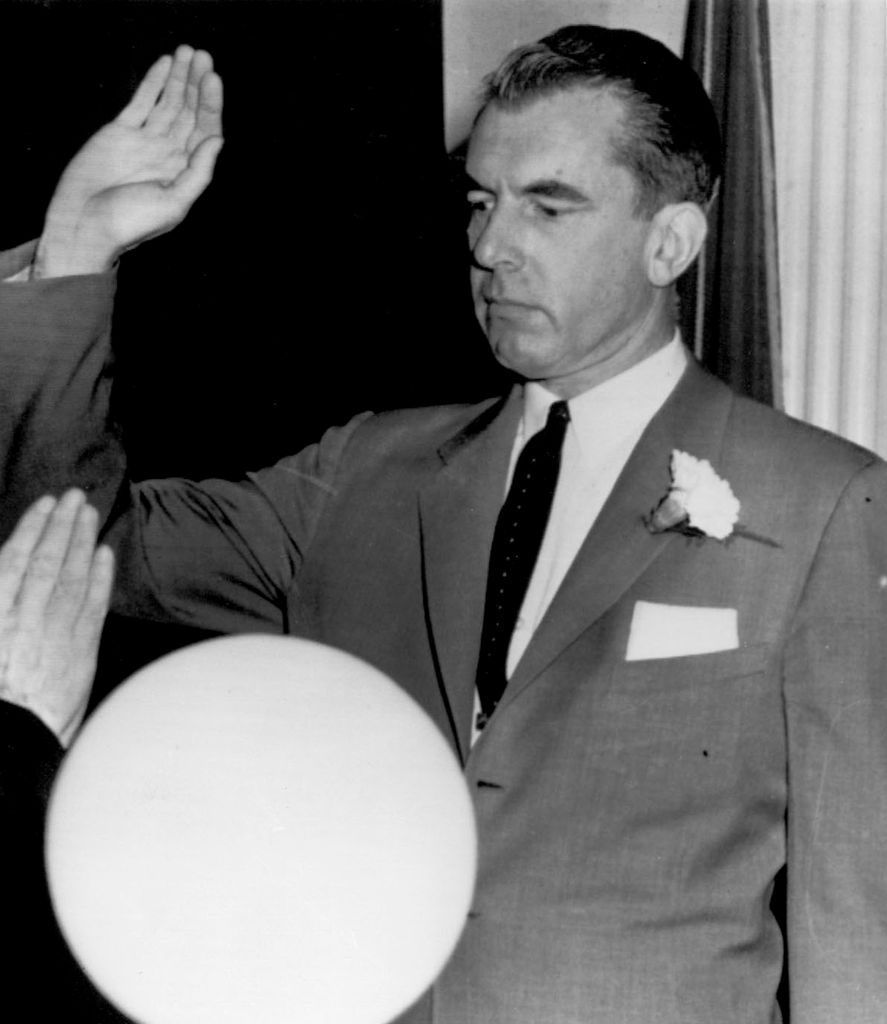

Robert Stafford (LLB’38, Hon.’59)

Robert Stafford didn’t intend to go into politics. Yet, he served the government in one capacity or another for more than 50 years and shaped some of the most significant environmental and education legislation of the twentieth century.

Stafford first entered the public sector in 1938 as a city attorney in his hometown of Rutland, Vermont, while practicing law alongside his father. After serving in World War II and the Korean War, he returned to Rutland and moved up the ranks in Vermont politics from deputy attorney general to attorney general, then lieutenant governor and governor. In 1960, he was elected to represent his state in the US House of Representatives. He served five terms before resigning in 1971 to accept an appointment in the Senate, filling the vacancy caused by the death of Winston L. Prouty. He would be reelected for the next 18 years.

During his time in Congress, Stafford was known as a steadfast advocate for the environment. One of his notable successes in the House was winning the passage of the Clean Air Act of 1970, the first federal law that addressed the national problem of air pollution. In the Senate, he chaired the Committee on Environment and Public Works and cosponsored the Wilderness Protection Act in the early 1980s. He also helped pass the Safe Drinking Water Act and led the successful effort to override President Reagan’s veto of the Clean Water Act.

One of his colleagues, Senator George Mitchell, noted Stafford’s knack for reaching across the aisle to get things done. “Against that tide, he was able to lead the Congress in adopting landmark legislation,” said Mitchell.

Stafford also drove monumental strides in education. He sponsored the Education for All Handicapped Children Act of 1976, which required public schools to teach children with disabilities in mainstream programs, and supported legislation to help the children of low-income Americans attend college. “Every American child has a right to an equal educational opportunity,” he said.

In 1988, Congress renamed the Federal Guaranteed Student Loan program the Robert T. Stafford Student Loan program in honor of his work on higher education. During that same year, Stafford helped pass a law, now known as the Robert T. Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act, or Stafford Act, which coordinates federal natural disaster assistance for state and local governments.

Stafford died in his hometown on December 23, 2006. Senator Patrick Leahy remembered his fellow congressman in a statement: “He touched the lives of millions of ordinary Americans through his leadership on education and environmental policy, in the finest tradition of public service. And he gave the nation a lifelong lesson in civility and decency in the finest tradition of his beloved Vermont.”

Robert Stafford is sworn in as governor of Vermont in 1959. | AP Photo

A staunch environmentalist, Stafford was present when President Jimmy Carter signed the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act in 1980. | Dennis Cook/AP Photo

In 1988, Congress renamed the Federal Guaranteed Student Loan program the Robert T. Stafford Student Loan program in honor of his work on higher education. | AP Photo

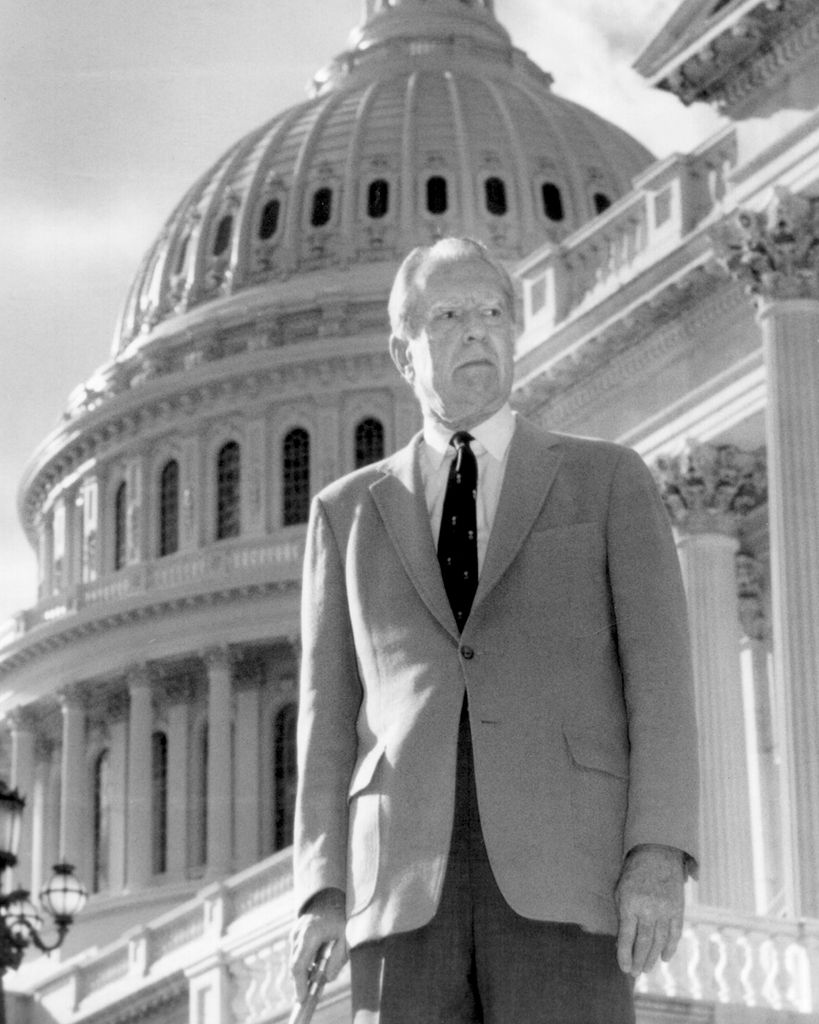

Edward Brooke (LLB’48, LLM’50, Hon.’68)

After the bombing of Pearl Harbor shook the United States in 1941, Edward Brooke, like many of his fellow Americans, enlisted to serve his country. But while in the Army, Brooke, a Black man, found irony on the frontlines: how, he wondered, was he fighting abroad to preserve democracy when Black people were denied rights in his own country?

When Brooke returned home from the war, he focused on his legal education and opened his own practice in Roxbury, a predominantly African American community.

In 1950, Brooke ran for a seat in the Massachusetts House of Representatives, but his limited political experience and lack of clear party affiliation cost him the election. He won the Republican nomination two years later but fell short in votes again.

Following these disappointments, Brooke took a hiatus from politics to focus on his legal practice. That is, until 1960, when he was appointed as chairman of the Boston Finance Commission, a position he held for two years before he was elected the Massachusetts attorney general. As the state’s top advocate, Brooke fought corruption head-on, including overseeing the indictments of a former governor, two speakers of the Massachusetts House, and a public safety commissioner.

In 1966, Brooke ran for a seat in the US Senate, billing himself as a “creative Republican” who supported “the establishment of peace, the preservation of freedom for all who desire it, and a better life for people at home and abroad.” He was elected with 62 percent of the vote, making him the nation’s first Black congressman in 85 years and the first to win by popular vote.

As a Republican representing an overwhelmingly Democratic state, Brooke quickly earned a reputation for crossing party lines to get things done. But while he supported issues such as fair housing policies and civil rights, Brooke emphasized that he represented not just African Americans but all Americans.

Among Brooke’s achievements in the Senate was a seat on President Lyndon B. Johnson’s Commission on Civil Disorders, which sought solutions to rioting in major cities during the 1960s. Brooke was also a champion of the Civil Rights Act of 1968 and the Equal Credit Act, which ensured women the right to establish credit. He also fought to uphold Title IX, a law that guarantees equal educational opportunities for girls and women.

After leaving the Senate in 1978, Brooke continued to serve the public, including appointments on President Reagan’s Commission on Housing and the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians.

In 2004, President George W. Bush awarded Brooke the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor. Five years later, President Barack Obama presented him with the Congressional Medal of Honor.

Barbara Jordan (LLB’59, Hon.’69)

Barbara Jordan rose to prominence as a legislator from Houston’s predominantly Black Fifth Ward during the 1960s. In the decades that followed, the Texas representative made her mark as an influential lawmaker, defender of the US Constitution, and an impassioned voice during the Watergate impeachment investigation.

Jordan first dipped her toe into politics when she managed a widespread get-out-the-vote program for John F. Kennedy’s 1960 presidential campaign. She ran twice, unsuccessfully, for the Texas House of Representatives before being elected to the Texas State Senate in 1966. The win distinguished Jordan as the first woman ever elected to the legislative body and its first African American member since 1883. During her second term, she earned the title of president pro tempore of the Texas Senate, marking another distinction as the first Black woman in the US to preside over a legislative body.

Jordan fought to extend federal civil rights protection to more Americans from her first days as a legislator. She quickly earned a reputation as an effective lawmaker, sponsoring measures establishing the state’s first minimum wage law, antidiscrimination clauses in business contracts, and the Texas Fair Employment Practices Commission.

In 1972, Jordan was elected to a US congressional seat that encompassed a swath of downtown Houston with a predominantly Black and Hispanic population. The win made Jordan one of the first African Americans elected to Congress from the Deep South in the twentieth century. Soon after, she earned a seat on the House Judiciary Committee, an appointment she would keep during her three terms in Congress.

Jordan became a household name in the summer of 1974, when the House Judiciary Committee held hearings on the impeachment of President Richard Nixon. During her nationally televised opening remarks, Jordan argued for Nixon’s indictment for high crimes and misdemeanors. “My faith in the Constitution is whole, it is complete, it is total,” she said. “I am not going to sit here and be an idle spectator to the diminution, the subversion, the destruction of the Constitution.”

Jordan’s commanding presence during the hearings cemented her reputation as a respected national politician and protector of the US Constitution. In Houston, a series of billboards sprang up, proclaiming: “Thank you, Barbara Jordan, for explaining the Constitution to us.”

During the 1976 presidential campaign for Jimmy Carter, Jordan delivered a spirited keynote address at the Democratic National Convention (DNC) — making her the first woman and first African American keynote speaker in the nearly 100-year history of the convention. Following the election, President Carter interviewed Jordan for a cabinet position, though he did not offer her the role of attorney general, rumored to be the only post she would accept.

Jordan declined to run for reelection to a fourth term in Congress, yet she would continue to lecture nationwide on national affairs and delivered speeches at the DNC in 1988 and 1992. She taught at the University of Texas in Austin until the early 1990s. In 1994, President Clinton appointed Jordan to lead the US Commission on Immigration Reform. That same year, he awarded her the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

Jordan died in Austin, Texas, on January 17, 1996. Newspapers across the country celebrated that trail she blazed for generations of women in politics. “She left Congress after only three terms, a mere six years,” the editors of the New York Times wrote. “No landmark legislation bears her name. Yet few lawmakers in this century have left a more profound and positive impression on the nation than Barbara Jordan.”

William Cohen (JD’65)

In 1974, during his first term in Congress, Time magazine named William Cohen one of “America’s 200 Future Leaders.”

The honor came shortly after Cohen found himself in the spotlight as a member of the House Judiciary Committee tasked with investigating the Watergate scandal. The freshman lawmaker from Maine was one of the first to break with the Republican party and vote to impeach President Richard Nixon. “I have been faced with the terrible responsibility of assessing the conduct of a president that I voted for, believed to be the best man to lead this country. But a president who in the process by act or acquiescence allowed the rule of law and the Constitution to slip under the boots of indifference and arrogance and abuse,” Cohen said in his statement to Congress.

Cohen served three terms in the House before defeating a highly respected incumbent, William Hathaway, to represent Maine as a senator. He sat on several high-profile committees during his time in the Senate, including the Armed Services Committee and the Governmental Affairs Committee. He made waves on the Iran-Contra Committee, where he was a leading critic of the Reagan administration’s actions. As a member of the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, Cohen claimed that the CIA had lied to cover up its involvement in human rights abuses in Guatemala.

Over the years, Cohen developed a reputation as a moderate Republican with liberal views on social issues and conservative views on defense and foreign policy. He was instrumental in drafting notable laws related to defense, including the Montgomery GI Bill and the Information Technology Management Reform Act, which improved the way government agencies use IT.

In 1996, after winning six consecutive Maine elections by landslide margins, Cohen shocked his constituents—and the country—when he announced he would not seek reelection. But his plans to return to private life were thwarted when President Bill Clinton called on him to lead the Department of Defense. It marked the first time in modern US history that a president asked an elected official from the opposing party to join his cabinet.

During Cohen’s tenure as secretary of defense, the US military conducted operations on nearly every continent, including the most significant air warfare campaign since World War II in Serbia and Kosovo. In addition, he traveled the world to meet with foreign leaders in sixty countries and tackled a host of social issues back home, including the treatment of gay and lesbian soldiers serving in the military and the role of women in combat.

After leaving the post of defense secretary in 2001, Cohen founded the Cohen Group, a business consulting and lobbying firm, with three former Pentagon officials. He has also served on study groups and committees at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, the School for Advanced International Studies, and the Brookings Institute.

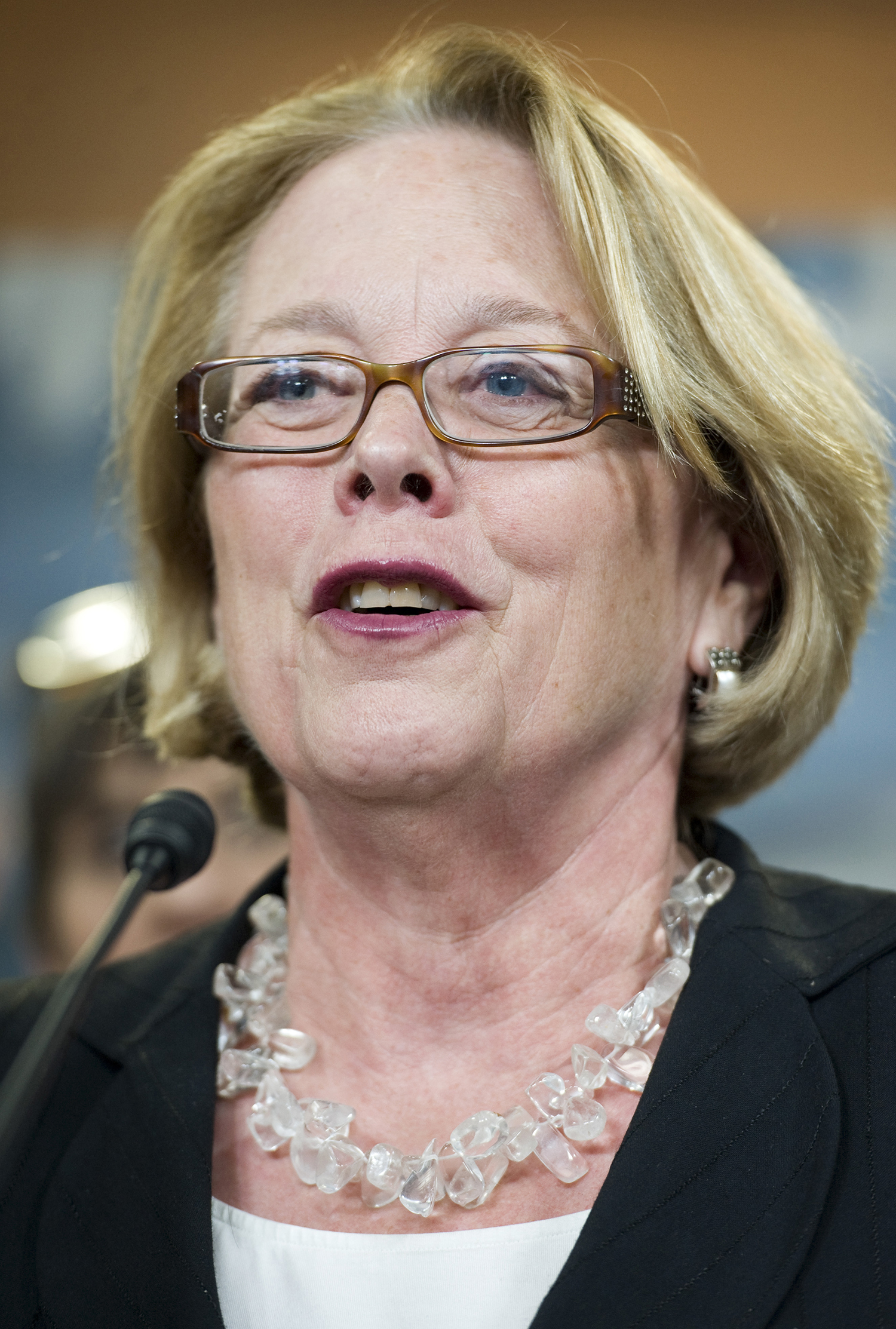

Niki Tsongas (JD’88)

When Niki Tsongas ran in a special election to the House of Representatives in 2007—the same seat that her late husband, Paul Tsongas, once held for a decade—former President Bill Clinton campaigned on her behalf. “Congress will be a better place because she is there,” Clinton told the crowd at a campaign event in Lowell.

When she won the election, Tsongas became the first woman to represent Massachusetts in Congress in a quarter of a century. She also realized the immense responsibility on her shoulders to make Congress a better place. “You weigh in on every issue we face as a country,” she said. “So it’s an opportunity never to be squandered.”

During her 12 years in office, Tsongas was a tireless advocate for universal healthcare and a public health insurance option. “My very first vote in Congress was cast to expand healthcare for women and children,” she said. “I helped pass life-saving healthcare reform legislation, the Affordable Care Act, and have fought to defend its protections for millions of Americans.”

Tsongas was also an avid supporter of LGBTQIA+ rights. She cosponsored the Respect for Marriage Act, which repealed the 1996 Defense of Marriage Act, and voted for the Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell Repeal Act of 2010, which enables gay and lesbian servicemembers to serve openly in the military.

For Tsongas, the daughter of a career military officer who survived the attack on Pearl Harbor, serving as a senior member of the House Armed Services Committee had special meaning. She was a top Democrat on the Subcommittee for Oversight and Investigations, where she focused on sexual assault in the military and supported legislation to improve the treatment of women in the armed forces. “I’m especially proud of the role I have been able to play in challenging the ways in which women are treated in the military, understanding that if you change the culture of one of our country’s rightly honored bedrock institutions, you can change a country,” she said.

When Tsongas announced in 2017 that she would not seek another term, she reflected on how far women in Massachusetts politics had come since her first term in office. “Since that door cracked open, the Commonwealth has elected another female member of Congress, our first female US Senator, and in my district, 50 percent of our state legislators are now women.”