Drawing on Law to Study AI

Researcher Vasanth Sarathy (’10) is exploring how AI algorithms can be deployed to flag and counteract misinformation online, in part by identifying spurious arguments.

Drawing on Law to Study AI

Researcher Vasanth Sarathy (’10) is exploring how AI algorithms can be deployed to flag and counteract misinformation online, in part by identifying spurious arguments.

Photo by Ciara Crocker

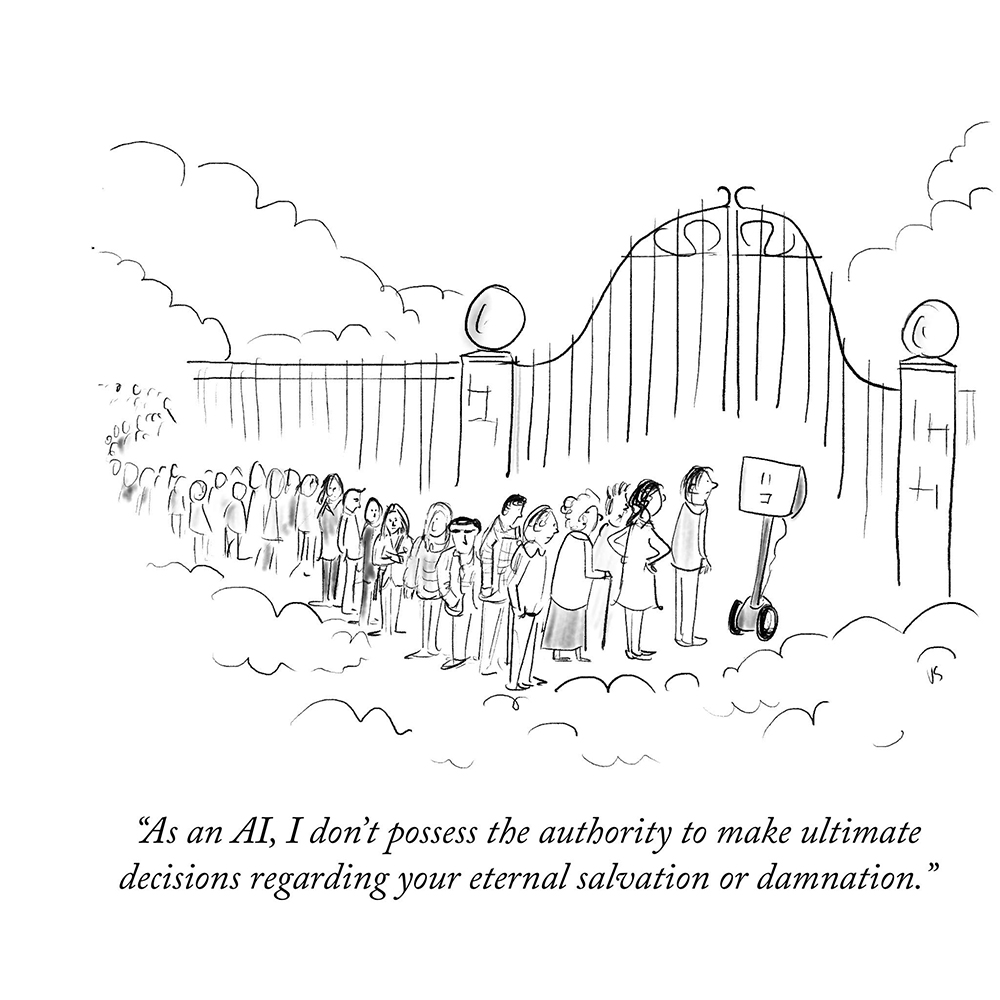

AI isn’t funny. At least, not yet.

Although artificial intelligence is being tapped for ever more sophisticated tasks—from drafting legal documents to debugging code—it hasn’t been able to figure out what exactly makes us humans chuckle.

Is it even possible for AI to master wit? Vasanth Sarathy (’10)—lawyer, artificial intelligence expert, cartoonist, and Tufts University faculty member—can’t say for sure. He’s been tinkering with an AI tool to generate cartoon ideas, but progress, he admits, is slow. “It doesn’t understand why something is funny,” he says, “which may be a very personal human thing, a consequence of life experiences. In which case, it’s even harder for an AI system to replicate it.”

Even AI specialists like Sarathy, who holds a doctorate in computer science and cognitive science in addition to his JD, have been astounded by the sophistication and wildfire adaptation of generative technology. In just the past year, large language models such as OpenAI’s GPT-4, which are trained on internet content to identify patterns and predict language, have been increasingly deployed to write essays, reply to patients’ queries to their doctors, and even create artwork and music. Their popularity and rapid deployment—in just two months after its launch in November 2022, ChatGPT had amassed more than 100 million users—have heightened fears about the morals and ethics of this astonishingly powerful tool.

Sarathy is more curious than anxious, perhaps because he sees AI’s potential to solve problems it has been accused of creating. He is particularly interested in how AI can be leveraged to combat rampant disinformation. He’s focusing on how AI’s algorithms can be deployed to flag and counteract misinformation online, in part by identifying spurious arguments.

Picking apart arguments is, not surprisingly, a skill at which lawyers excel, Sarathy says. The logical reasoning section of the LSAT is a perfect example: aspiring lawyers read excerpts and then pinpoint implicit assumptions and flaws in reasoning. This type of analytical thinking becomes second nature to litigators and appellate lawyers, but it’s challenging for those who lack training or practice in thinking critically. This is the audience most likely to accept fake information and dubious arguments and then spread untruths.

Helping humans with critical thinking is something that machines can do, I think. We’re sort of scratching the surface of that.

“We don’t have the capacity to quickly do critical thinking at the level we need to, to combat disinformation,” Sarathy says. “If the language is fluent and the argument seems relatively good, we tend to believe it. That’s really challenging because…a little bit of critical thinking can go a long way…. Helping humans with critical thinking is something that machines can do, I think. We’re sort of scratching the surface of that.”

As a member of a multidisciplinary team that includes a social anthropologist, Sarathy has been exploring how to foster online communities that encourage healthy but respectful discourse while respecting cultural differences in speech and intent. “You have systems that can understand the language, but then you introduce social science theories and the extensive work that people have done in anthropology, studying different cultures…and then you have the AI system produce responses that are more nuanced and more informed,” he says. The project is in its earliest stages, undergoing extensive testing to see how effectively the AI system can generate speech that is relevant, useful, and accurate. Eventually, the group might partner with government agencies and social media companies.

One of the biggest shortcomings of AI systems is that they lack a model of the world humans build over a lifetime. People spend years weaving a rich and vast contextual network of memories, knowledge, facts, education, and connections. When listening to or making an argument, we tap into a deep web of experience to formulate it, understand it, and evaluate its merits, Sarathy says. “There’s rhetoric, there is understanding, forming mental models of the other person, and understanding what they know so that you don’t just repeat what they [already] know. You’re telling them something new but also building on what they know so that they believe you. There’s a notion of trust and persuasiveness.”

This uniquely human ability to blend experience and context also helps pinpoint why AI can’t quite nail humor. A single-panel cartoon—the kind Sarathy draws and the New Yorker showcases—appears to be a simple pairing of a sketch and a line of text. A clever cartoonist presents a familiar situation, such as a dinner party or a parent-teacher conference, with a caption that tweaks the typical scenario. That mismatch between expectation and “reality” is the crux of humor, but the interplay between the art and the words matters, too.

“That’s where the human piece comes in,” Sarathy says. “If your timing is off, if you wait too long, then [readers] are going to think of that situation and not find the joke funny. But if you do it too soon, they’re not going to have enough time to form that first mental model of the situation. It’s a beautiful dance to get it right. AI systems can replicate what’s already out there in terms of captions and such, but they’re not original enough yet. They can’t come up with completely different ways of thinking or new ideas.” Which means ChatGPT won’t be winning the New Yorker’s caption contest anytime soon.

Sarathy draws on his experience as a cartoonist and lawyer in his AI research, a field that is by nature integrative. “We’re working with humans, and so all the issues that we face with these AI systems are going to be inherently multidisciplinary,” he says. “We’re not just going to have computer scientists build AI tools and then put them out there. That’s one of the things that I’m excited about: I’m able to bring my legal background and some of my social science background to this technical side of things and work on both those issues and bring people on these two sides together.”

Sarathy had no plans for a legal career when he studied electrical engineering on a full scholarship at the University of Arkansas or as he pursued a doctorate at MIT in the early 2000s. But while in graduate school, he learned that Boston-based law firm Ropes & Gray needed engineers who could understand the complex technology behind clients’ inventions. Intrigued, Sarathy made a career pivot. He registered to practice at the US Patent Office and took the patent prosecution exam, which does not require a law degree. Sarathy enrolled in BU Law five years later while working full time. “I don’t know how I did that,” he admits, “but it was absolutely insane.”

While on the partner track, he represented Google, MIT, medical device makers, healthcare companies, and Apple, and he collaborated with litigators and advised on intellectual property, data security, and privacy issues. But Sarathy found himself pondering how, exactly, innovators work their magic, spinning an insight or pain point into a start-up or a patent-worthy invention. “It just became a thing I wanted to study: how the human mind works and how we humans are creative. How do we come up with new ideas? How do we invent things?” Sarathy, then 35, headed to Tufts in 2015 to pursue a doctorate in computer science and cognitive science.

He spent nearly three years at research firm SIFT (Smart Information Flow Technologies), probing questions such as the parameters of consent in human-robot interactions. It’s less far-fetched than it might seem. A robot waiter, for example, should be programmed to clear a diner’s plate only when the diner has provided “consent cues,” such as placing her utensils in the “finished” position on her plate or sitting back from the table. As robots become more integrated into society, human social norms will provide implicit and explicit consent cues for interactions, Sarathy wrote in a 2019 research paper.

“A lot of the consent work was based on my legal training,” he says. “I would not have been able to write that paper if it had not been for the fact that I went to law school and took classes in torts.” He continues to tap his legal experience, crediting his years in law school and practicing law with sharpening his writing and thinking—and giving him ample fodder for Legally Drawn, the (now-defunct) cartoon blog he launched as a BU Law student.

Though the legal profession will increasingly outsource tasks such as document review to AI tools, Sarathy is confident that AI is a poor substitute for the experience, context, and nuanced analysis that trusted attorneys provide their clients. “I’m not saying that these systems are bad,” he says. “I use them in my work as well. I’m just saying that there’s not a risk that lawyers are going be out of their jobs anytime soon.”

Lawyers and ethicists will, however, inevitably tangle with AI’s legal gray areas. Leveraging ChatGPT’s open-source software, developers and start-ups have been building apps that let users craft college application essays and create images in the style of famous artists and celebrity designers. When the large language models produce new images after being trained on copyright-protected images, are those creations copyright violations?

“We don’t know where the law is going to end up on that,” Sarathy says. “It’s not clear what the law says about this situation. You’re going to have to think about the legal consequences. What are the different ways that AI systems can be more…transparent [and] aligned with human values?… The best-case scenario is that we humans get better in figuring out which AI tools are good and which ones are not, because they’re all going to be there, and they’re all being used.”