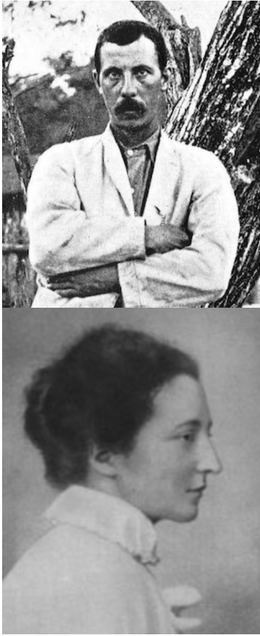

W. Barbrooke Grubb

Missionary Explorer & Anglican Layman

Mary Bridges Grubb

Wilfrid Barbrooke Grubb (1865-1930), born near Edinburgh, Scotland, was an explorer and missionary in the Chaco regions of Paraguay, Bolivia, and Argentina with South American Missionary Society (SAMS). He was the first SAMS agent able to establish long-term mission stations in the Chaco area, and so furthered the Society’s goal of reaching the continent’s “aboriginal” peoples. Grubb was promoted by the Society as the “Livingstone of South America,” since much of his early work involved mapping the topography and documenting the culture of an inland region largely unknown to Europeans at the time.

In 1884, when he was about nineteen years old, Grubb applied to work for SAMS and was licensed as a Lay Reader in the Church of England. In March 1886, the Society sent Grubb to the existing mission in the Falkland Islands to serve as lay catechist. During this time, he met and became engaged to Mary Ann Varder Bridges, whose father, Thomas Bridges, was an established SAMS missionary.[1] It was not until 1901 that they were able to marry, and Mary spent her married years living at times in the Chaco region with Grubb, at times in Scotland, and at times with her family in Tierra del Fuego.

In 1889, SAMS sent Grubb to Paraguay to follow up the work among indigenous peoples started by Adolfo Henricksen. Over the course of the 1890s, Grubb built various mission stations in the Chaco region, extending from the River Paraguay westward toward the contested border with Bolivia. His associates included Andrew Pride (arrived in 1892), who often served as photographer, and Richard J. Hunt (arrived in 1894), who did much of the linguistic work and translation, including making a dictionary for the language used by the Enexet tribe.[2] The first baptisms were performed in June 1899, and the first church building was constructed around this time.

From his initial years in the country, Grubb maintained cordial connections with the Paraguayan government, who as early as 1892 had named him “Pacificator of the Indians.”[3] Though his exact position or title is unclear, Grubb at various times referred to himself as an official representative of the Paraguayan government in the Chaco region.[4]

Grubb took various furloughs to promote SAMS work in England, Scotland, Ireland, Canada, and the USA. On one of these trips, he gave speeches at the Ecumenical Missionary Conference in New York in 1900. Although he did not attend the Edinburgh Missionary Conference of 1910, he did send in a report on indigenous religion to D.S. Cairns, who chaired the commission on non-Christian religions.

During the second decade of Grubb’s work, his efforts in Paraguay reached a high point in 1907 with the establishment of Makthlawaiya, a mission station intended to be a “Christian colony.” In 1910, Grubb began investigating the possibility of starting missions in the Bolivian and Argentinian portions of the Chaco region. He started some mission work in northern Argentina under the auspices of American sugarcane planters by the last name Leach, and a SAMS mission with the Mataco tribe was begun between 1914-1915.

Grubb took a deep interest in the customs, crafts, beliefs, and lifestyles of the various indigenous groups of the Chaco. However, he also viewed them through his ideas of racial hierarchy, labeling various groups as more or less “civilized” or “intelligent” than others. As a citizen of the British empire, Grubb expressed optimism at the spread of Western civilization in South America, though he thought it was the Christian’s responsibility to prevent unscrupulous businesspeople from abusing indigenous peoples or introducing vices like drunkenness.

During the 1910s, Grubb took extended furloughs to Europe for his health and for promotional speaking. In 1921, he left South America for the final time, and his wife Mary died the following year. Grubb lived with his two daughters, Bertha and Ethel, and continued promotional speaking in support of native evangelists in the Chaco during the last decade of his life. He died at his home near Edinburgh in May 1930.

By Morgan Crago

Uncovering the “Real” Barbrooke Grubb: A Case Study in the Difficulties of Reading Missionary Literature

As a mythologized “missionary hero” figure, discovering what Barbrooke Grubb himself was like is a complicated historical task. This difficulty derives from the needs of his sending organization, the South America Missionary Society. This Society grew from the vision of Allen Gardiner, a British naval captain, who desired to open mission work in Tierra del Fuego. Though making several attempts, Gardiner was never able to secure the support of the Church of England’s Church Missionary Society (CMS), which turned him down in part because of the difficulty of the location, and in part from a desire not to interfere in Roman Catholic territory. Gardiner and a few followers, therefore, struck out on their own, forming the Patagonian Missionary Society in 1844, which was later renamed South America Missionary Society.[5] In a society independent of the CMS, which might have provided stronger financial support, Grubb’s stories became a means of generating interest and, hopefully, needed funds as well. Many of the books ostensibly written by him are in reality edited works designed to entertain, promote, and inspire, and therefore focus on the more sensational aspects of his activities.

This essay attempts to untangle these sources and separate Grubb the person from Grubb as he was portrayed by others. In order to do this, I focus on Grubb’s thinking on two intertwining topics—his view of the culture and religion of the peoples of the Chaco area, and his view of the proper purpose and methodology of missionary work. I first survey Grubb’s own attitudes through his updates in the South America Missionary Magazine and speeches he gave at mission conferences, and then compare these attitudes with those presented in his laudatory biography, The Livingstone of South America, written by his colleague Richard Hunt.

In his reports to the South America Missionary Magazine, Grubb presented two contrasting views of the culture of the local people. On some occasions, he was impressed with their affection for their children, the men’s care for their wives, and their generosity, to the point of saying he preferred “dealing with the Indians to dealing with civilised people.”[6] While those living in the eastern portion of Paraguay often feared the Chaco peoples as hostile, Grubb defended their reputation by explaining that they had to defend themselves from poor treatment by the national government.[7] He operated with a sense of racial hierarchy, however, and did not consider all ethnic groups as equals. For instance, he thought “the inhabitants of the Chaco appear to have been originally of a low type, leavened later on by an influx of Inca and other Peruvian Indians.”[8] Grubb also had a higher opinion of the Chaco groups who lived further inland, since he thought the people close to the coast of the River Paraguay were “very much debased by contact with so-called Christians.”[9]

In 1890, when he had newly arrived in Paraguay, Grubb thought the best missionary method would be to travel among the people and get to know their ways, “instead of trying to draw them to the Mission Station.” Within this same report, however, he articulated what would soon become a mantra for the rest of his career—the native peoples would have to settle in villages and adopt a sedentary lifestyle. “What is wanted,” he said, “is to stir them up to industry, to encourage them to care for and increase what they have, to live apart in families, and to keep away from traders.”[10]

Grubb believed that the onset of Western civilization in South America was inescapable, and that it was the missionary’s task to make sure this inevitable process unfolded morally, peacefully, and (as he believed) fairly. As early as 1890, he said

If the Mission is to succeed in teaching and saving Indians, it must advance surely, boldly, and quickly. Other enterprises are advancing, and they come in armies in comparison with us. They have wealth, and stand at nothing…The majority by far would rather have the Indian’s room than his company; but it is well known that the mere presence of a missionary has a certain protective power on behalf of the Indian.[11]

In Grubb’s mind, his attempt to convert people’s lifestyle as well as their religious beliefs was an entirely legitimate missionary goal. In an 1899 issue of the Magazine, he asked rhetorically, “in addition to enlightening the spiritual darkness of these people, can we not also help them to improve in temporal matters?” Although he claimed that “the formation of a strong and pure Christian church is of course our first and chiefest aim,” he thought it equally important to “civilize” the people so they could “profitably occupy and develop [their] native land.”[12] Since Grubb believed that the national governments in South America were poised to exterminate the indigenous populations they considered dangerous and economically unproductive, he thought the missionary’s appropriate task was to re-shape the indigenous people into populations economically attractive to the state.

Grubb often expressed these religious and economic rationales for mission in the same breath, with no sense of inconsistency. In a Magazine article of 1908, he described how the mission was encouraging indigenous women to have several children, in part because he believed filling the earth was God-ordained. However, this divine mandate was not the only reason behind his encouragement of population growth:

Men of the world can hardly fail to take a lively interest in the development of possible new markets for the world’s enterprise, and those especially in Chaco lands can surely not fail to see the benefit of a numerous, trained and willing population of workers, with whom to develop the lands in which they have placed their capital…While we as a mission naturally devote our greatest energies to the moral and spiritual development of the people, we are practical enough not to neglect such training as will fit these people to take their proper place in this world.[13]

The Magazine is not the only source of Grubb’s thinking on these topics of indigenous culture and the purpose and method of mission. During a mid-career extended trip back to Europe and North America, Grubb spoke at the Scottish Geographical Society in January 1900 and at the Ecumenical Missionary Conference in New York, which took place about four months later (April 21-May 1). In his Geographical Society presentation, Grubb described some indigenous cultural practices, such as the custom of always sharing food with strangers, with a focus on the deficiency of these practices. Grubb remarked that while “many of the Indians would be fairly hard workers,” this requirement of hospitality prevented wealth accumulation. Any person who acquired more material goods would necessarily end up supporting a large number of poorer relatives because the people lacked “the moral courage” to argue that “‘if a man will not work neither shall he eat.’”[14] Their practices of destroying a dead person’s goods and vacating settlements where a death had occurred had similar effects. While recognizing that this system led to “equality and justice” with all at “a common level,” Grubb thought the custom was ultimately a “cancer that eats of the root of the industrious life of the people.”[15] To remedy this social lack, he thought “new wants must be created, and when such become necessaries of life, the people will work to get them, and the habit of industry will grow.”[16] The fear of spirits, which led to the relocations after a death, could be cured through “a pure, simple religion, none better than the simple, loving, liberal-minded, practical, and life-giving Gospel of our Lord Jesus Christ.”[17] If Europeans would come in to raise cattle (the best industry suited to this region short of permanent water sources), indigenous people could be hired as laborers. In short, a mixture of Christian teaching and cattle ranching was the solution to the social lack Grubb identified.[18]

Grubb continued promoting European and North American immigration for ranching in his speeches at the New York missions conference, but in this context he gave more attention to the problems this influx would bring to the region. Grubb described how he and his co-workers were “opening up” the Chaco area through their creation of an alphabet, dictionary, maps, and ethnographic studies. He worried, though, that “behind us emigration is now coming in a steadily advancing tide, and it is of the very worst kind you can find anywhere.” Settlers seeking to take advantage of indigenous peoples would pay only “the very worst gin” for rubber supplies.[19] Grubb therefore advocated an influx of Christian businesspeople, who would trade “useful articles and still have an ample profit,” as well as the development of cattle ranching in which local people were employed as ranch hands.[20] The Chaco peoples, though skilled in many crafts, he thought, “will require civil rights, protection of the Government, some capital to develop their country with, and good leadership.”[21]

Ten years later, Grubb reported his findings on the religions of the Chaco area for the Commission on “The Missionary Message in Relation to Non-Christian Religions” for Edinburgh 1910. In the portions of Grubb’s responses that D.S. Cairns chose to include in the commission’s report, Grubb appeared to have a more benevolent view of the people’s religion. “The more intelligent Indians,” he thought, “were entirely dissatisfied with their faith,” because their beliefs about marriage or the afterlife “clash with their keener reasoning.”[22] Moreover,

They agree to the last five prohibitions of the Decalogue, though they seldom observe them. They hold that the intention to do evil is evil, and punish for it as much as if the intention had had been carried out.[23]

In the excerpts, he also reiterated his earlier complaint from the Geographical Society address about the people’s “lack of will power and independence of character” that prevented individuals from breaking with their group.[24] In contrast with some other statements which will be addressed below, here Grubb taught that

The missionary should abstain from any superior aloofness from the native, and as far as possible, without unduly spoiling him, act towards him as to his own countrymen, teaching always that any superiority is the result of environment, educational advantages, and Christian privileges, and that the hearts of all are the same in the sight of God.[25]

At the very end of his missionary career, Grubb gave a speech before the Royal Geographical Society in 1919. In it, he noted some drawbacks in the invasive processes he had been associated with in the Chaco area. Cattle ranching near the River Bermejo had eliminated the thick grasses in many areas, creating rising clouds of dust.[26] The people of the Chaco themselves, with more widespread use of flint, had been burning the grasses to facilitate travel and keep down snakes and insects.[27] He had assisted the Paraguayan government in its surveying work, which land allocations had been sold to purchasers who were intending to sell later on at a profit. “Unfortunately,” in the course of surveying, “the Government did not reserve lands for the Indian population,” and the SAMS had needed “to secure what we require for the purpose of our Missions by private purchase.” Grubb thought “it would have been wiser if certain lands had been set aside for the aborigines…”[28] In spite of this neglect, Grubb believed the Paraguayan government desired to be fair to the indigenous peoples, in part because it had “heartily welcomed and fully approved the efforts of the South American Missionary society on their behalf.”[29] His prescriptive remarks were reminiscent of those he had made nearly twenty years ago in New York:

What the Chaco needs is not the establishment of great companies, but a great number of smaller settlers, and this can only be made possible if the Government facilitates men of small capital being able to secure land…[30]

In this speech, his depiction of indigenous culture was directly associated with these economic projects. On a pragmatic basis grounded in racial theories related to climate, he argued against those who saw no need “to endeavor to preserve these native races.” While parts of South America were suitable for Europeans, Grubb believed that much of the continent was “so situated climatically that only races adapted to the tropics can ever satisfactorily form the laboring class necessary for the development of these potentially rich regions.”[31] He considered these peoples, in the past, to have been in “a state of utter barbarism,” in part because the land “was quite unsuitable for the development of even a moderately cultured people,” although their “warlike” characteristics had protected them from the encroaching Spanish colonies.[32] To those who thought the Chaco peoples would never be “peaceful, industrious” and “law-abiding,” Grubb argued that the SAMS had proved otherwise, for they “have instructed many not only in the Christian faith and higher morality, but we have taught them many useful arts.”[33]

In sum, Grubb believed that in the face of an inexorably advancing Western civilization, the indigenous peoples of the Chaco region required a missionary’s strong guiding hand. New South American nation states would seek to profit from the Chaco lands in one way or another, and Grubb believed that by urging the people to adapt to cattle ranching and sugar plantation work, these nations could be persuaded not to abuse or destroy these groups. However, his benevolence did not go so far as to advocate for these groups to be allowed to keep up their way of life free from interference. Because he saw these groups as socially inferior, Grubb believed the “civilizing” and “Christianizing” process—though something that needed to be carefully shepherded—was an ultimate good for all concerned.

While all of the above remarks are based on writings from Grubb’s own hand, there is another side to Grubb as he is left to us in the historical record. This is the heroic and legendary version, promoted by SAMS and the other mission agencies and writers who later used his life as an inspirational tale. While these sources give us much the same picture of how Grubb viewed indigenous culture and religion and understood the purpose of mission work, some nuances will emerge in the comparison.

One such secondary source is Grubb’s biography, written shortly after his death by Richard Hunt, his SAMS co-worker. Hunt’s biography is unquestionably and entirely laudatory of Grubb’s work and choices.[34] Hunt relied on Grubb’s diaries and letters, though he did not describe his access to the materials or always provide specific dates. While Hunt occasionally quoted Grubb’s own words, this source is also an example of how Grubb’s image and travels were used and shaped by others for the purposes of increasing the publisher’s profit and raising awareness for SAMS.

One way to discern how this source presents Grubb’s opinion of indigenous culture is by looking at the book’s several stories about what Hunt and Grubb typically called “wizards” or “witch-doctors.” At one point in the text, Hunt summarized Grubb’s abstract opinion of them through this quotation of Grubb’s words:

While many of the native customs might profitably be retained and while it was wise that the chiefs should maintain their authority, I realised that it was otherwise in the case of the wizards. Their influence was entirely evil, and if Christianity was ever to take hold of the people, the wizards must cease to exist. Chiefs and people alike feared the witch-doctor, and although I knew that the experiment was dangerous, I felt that I must declare open war against them, and treat their threats and boasted powers with contempt.”[35]

While the statement may suggest Grubb felt some apprehension regarding these diviners and healers, the stories Hunt included typically depicted them as confused or incompetent.[36] For instance, on one occasion Grubb heard a commotion as he passed a village. He was informed that a woman was being tormented by evil spirits and that one of these healers was attempting to drive it out. According to Hunt, “Grubb at once saw it was simply a case of hysteria.” Grubb put some ammonia on a cloth and held it to the woman’s nose, and “the effect was instantaneous; much to the astonishment of the people.”[37] The healer later came to Grubb inquiring about the substance, so Grubb let him smell some himself, which apparently overpowered him. The point of the story, as told by Hunt and depicted in this drawing, is to stress the healer’s naiveté.

In another situation, Grubb was frustrated with a diviner’s chanting when he was trying to relax, so Grubb decided to plant an alarm clock near him. When it went off, the man was so frightened that he ran away. Grubb also spent some time teaching “conjuring tricks,” in order that his audience learn not to have faith in the actions of the diviners.[38]

In Hunt’s depiction of events, the missionaries were not concerned about how their perspective on these diviners could interrupt the social fabric. For instance, at the Argentinian mission named Algarrobal, Grubb persuaded a man named Martin Ibarra, a translator, to join the mission. He eventually became such an adherent that he would report other people’s misdemeanors to the missionaries. This role, Hunt observed almost without noticing, came at a steep social cost:

This steady adherence to the missionaries eventually brought him up against the witch-doctors, and for a time he was boycotted by some of the inhabitants and some of his near relations. [Ibarra] felt it deeply, but gave his time to his garden and other work and consequently thrived, while the others wasted their time and substance in maintaining the professional sorcerers and their cult.[39]

Consistent with his evaluation of others who chose to join the mission (or not), Hunt here suggests that “maintaining the cult” would have been a completely unnecessary and irrational occupation.

Apart from the specific interactions with the diviners and healers, Hunt’s depiction of Grubb’s interaction more broadly with the Chaco people’s spiritual beliefs similarly emphasizes the superiority of Grubb’s own sense that spirits had no agency. For instance, when Grubb spoke against the practice of burying a living child along with its dead mother, a “young chief” eventually took his side, saying Grubb “had powers unknown to their people” and would be able to “ward off the wrath of the mother.” In this “struggle for righteousness and humanity,” Hunt thought “Grubb might feel sure of Divine support.”[40] When he later heard of a woman who had killed her newly-born infant, “Grubb sent the native police and fetched her. She was then tried by the natives themselves and found guilty.” As punishment, Grubb suggested they require her to dig up the body and “carry it to the cemetery, where it was properly interred.”[41] On another occasion, several people accused Grubb of having communicated with a ghost. To prove that “he was so convinced that there was no spirit about,” Grubb said he would walk over to the grave. Hunt speculated that they may have commented on “his coolness and bravery.” When it was later revealed that the ghost was only from “an old woman’s dream,” Hunt remarked that it was “through such occurrences the natives’ superstitions were gradually weakened.”[42]

Throughout the text, Hunt also illustrated Grubb’s understanding of the purpose and intention of the ideal mission station. One quite evident purpose was to force people to become sedentary as a necessary step to moral development. Hunt remarked that

For the inculcation of the lofty ideas of Christianity, the creation of a right atmosphere and congenial environment was essential, and this could scarcely be secured without a fixed central home with its church and school.[43]

After describing the baptism of some new converts, Hunt reflected that the “next step was to create a suitable environment for the young converts to live out the Christian life.”[44] Another aspect of the moral benefits of this isolation related to keeping “uncontacted” indigenous people away from a perceived danger—a degenerate intermediate population of those living close to the River Paraguay who had negative contact with the Paraguayan or European culture and fell prey to drunkenness and other bad habits.[45] Hunt hinted that some people, perhaps in SAMS, “objected to Grubb’s cattle-farm and trading concerns, and wanted to keep secular and sacred matters in separate water-tight compartments,” but he unsurprisingly sided with Grubb’s methods.[46]

The ideal station would include schools and animal husbandry. The missionaries in Paraguay often found the school difficult to maintain, as the parents were often reluctant to leave their children behind all day. Providing a mid-day meal, it turned out, could sometimes override this problem.[47] The stations could become centers for trade and keeping domesticated animals, an aspect Grubb thought necessary “if the natives were to be protected from unscrupulous traders and the great lessons of business integrity and fair dealing were to be taught.”[48] One of his goals during the 1899-1900 furlough was to raise funds for a cattle farm. Hunt described that Grubb

Hoped to give employment to natives so that by this means their social conditions might be improved and their livelihood made less precarious. His plan included the settling of some of the more intelligent Christians on little farms of their own.[49]

The purposes of the Paraguayan Chaco Indian Association, another cause Grubb was eager to promote, was “to enable the people to obtain profitable work and industrial training, and thus to localise them at the mission stations, where they could be more efficiently dealt with.”[50]

Another goal appeared to be, aside from creating a sedentary society, to preserve indigenous culture to some extent. In the colony, special prizes were given to mothers with four or more children to encourage having larger families, “with the object of impressing on the people the necessity of maintaining the population and thus continuing to exist as a people.”[51]

All through his description, Hunt consistently described the mission process as unquestionably beneficial for all parties involved. In the establishment of missions closer to the Bolivian border around 1914, Hunt described how the mission had managed to acquire a piece of land. Since there were no indigenous people living on it already, the missionaries had to invite some to come, something many of the more elderly did not want to do. Hunt’s commentary on this choice was that “they made a great mistake and missed a fine opportunity for advance in every way.”[52]

This confidence in the benefits of residency on a mission station caused the missionaries on at least one occasion to go beyond manipulation and actually force a person to relocate. When they were just starting the Algarrobal station in Argentina, Hunt remarked that “it was absolutely imperative to secure an adherent.”[53] Although they had made the acquaintance of an older man named Joaquin, they could not persuade him to relocate his family to the mission site. Therefore, Grubb went to his house and began to pack the man’s goods to cart them away to the mission. As Hunt described the scene, as they were taking his things away,

The poor man realised that resistance was hopeless and excuses futile, so he lent a hand to dismantle the house and load it into the cart…In this way the first settler was secured, and he never regretted the removal. Still stubborn, a confirmed grumbler, something of a recluse, he continued for many years staunch to the Mission and faithful in his work.[54]

This sense that the missionaries innately knew what was best for the indigenous people surfaces throughout the biography and fits in with other depictions of the people as fearful, deceptive, or lazy.

On the whole, this comparison of Grubb’s own writings and speeches with the depictions drawn in Hunt’s biography reveals a strong overlap of outlook. Both categories of writing evidence a paternalistic attitude toward the Chaco peoples, portraying them as somewhat childish but capable of adopting a European lifestyle and economic habits if missionaries would use their persuasive powers. Grubb’s interest in cattle ranching in particular comes through in all the writings. His interest in collaboration with non-mission-related institutions, such as the Geographical Society, surveying teams from the Paraguayan government, or Argentine sugarcane plantation owners is revealed in all the sources as well. Even the sensational tone is not completely of Hunt’s fabrication. Grubb was not above using his experiences as entertainments for his audience, as was evident in some of the language in his speech at the New York Missionary Conference of 1910:

At night goats and sheep continually prance about, and lucky you are if you do not have the wind knocked out of you two or three times during the night. The food is not choice!…[55]

Nevertheless, Grubb’s own writings do provide some points of contrast with the image portrayed by Hunt. His opinions about the diviners seem to be more serious and less belittling than the stories that Hunt told to amuse his readers. In his speech in New York, Grubb described the fearful influence of the diviners on the rest of the people, rather than turning to one of Hunt’s success stories, such as the one where Grubb was able to force several of these leaders to pay in sheep for damaging the roof.[56] Grubb’s later writings for the periodical Folklore, written in the very last years of his life, also reveal a more extensive interest and knowledge on Grubb’s part about indigenous cosmology than is evident in the biography.[57] In the article on “The Mythology of the Guarayo Indians,” he described this people’s beliefs about the journey into the afterlife.[58] When the traveling soul finally arrived through all the trials to the blessed place, Grubb said, the person would receive a bath, in which “he loses entirely, the odor which he has contracted by his contact with the Christians; it creates a long and plentiful crop of black hair, and he becomes the most elegant and beautiful youth that may be pictured.” In this study, Grubb at least perceived that some groups were frustrated by the Christian incursions into their area.

Grubb also reveals some inconsistency about the demeanor in which a missionary ought to approach the peoples of the Chaco. In Hunt’s biography, and in some of the books written in Grubb’s name, he advocated a very domineering approach. In his remarks selected for the report for Edinburgh 1910, however, Grubb recommended a much more charitable demeanor, avoiding “superior aloofness” and acting “toward him as to his own countrymen.”[59]

What this comparison shows is the complexity of determining the outlook of an individual person whose activities and statements were so likely to be pressed into the service of various causes. The comparison does not reveal that Grubb was entirely, or even mostly, misrepresented or manipulated by others’ depictions or editing of his thoughts and writings. However, enough differences arise that this comparison serves as a caution, reminding those who work with missionary writings to pay close attention to context and authorship when depicting the thoughts or attitude of a specific historical figure.

Commentary on the Sources

Sources on Grubb’s life and work come in different forms. Grubb wrote several articles himself, for both the SAMS Magazine and for other mission-related purposes, as well as for geographical and anthropological journals. Grubb also gave two speeches at the Ecumenical Missionary Conference held in New York in 1900, both of which were published. One untitled speech contributed to the section on “Incidental Relations of the Missionary to Science, Commerce, and Diplomacy,” while the other reported on “The Indians of South America.” When D.S. Cairns requested information from missionaries for the commission on the “Missionary Message and the Non-Christian Religions,” Grubb was one of those he contacted. Grubb’s submitted responses are unpublished, but excerpts are interspersed throughout the commission’s report in the chapter on “animistic religions.”

Three books, Among the Indians of the Paraguayan Chaco (1904), An Unknown People in an Unknown Land (1911), and A Church in the Wilds (1914), are purportedly written by Grubb, though they evidence the strong editorial hand of others. In the case of the first book, Bishop Waithe Stirling, in his preface, noted that he had visited Grubb on occasion and hoped that this account would bolster support of the SAMS work. The main text is written in third person with Grubb as a character, interspersed with extensive but uncited quotations of Grubb’s own words. Gertrude Wilson, listed as editor, presumably compiled the text, though Stirling does not comment on her hand in the text’s composition in the preface. An Unknown People was compiled by H.T. Morrey Jones. He first interviewed Grubb, combined these dictated notes with his own knowledge of SAMS work in the Chaco, and then crafted a text in which Grubb spoke in first person. According to Richard Hunt, this book came about as a result of the Seeley & Company representatives becoming interested in Grubb’s work during his trip to England in 1909-1910, when Grubb was participating in the “Africa and East Exhibition.” Hunt explicitly refers to Grubb and Morrey Jones as “joint authors.”[60] The third text, A Church in the Wilds, was also edited by Morrey Jones, and while no preface describes the composition of the text, it is also written in first person. Given the filtered nature of An Unknown People, it is difficult to know to what extent we hear Grubb’s own voice, or that of Morrey Jones, in this work. The Student Volunteer Movement’s Selected Bibliography of Missionary Literature of 1912 includes Among the Indians of the Paraguayan Chaco and An Unknown People. SAMS also provided copies Among the Indians of the Paraguayan Chaco to the “passenger steamers of the Royal Mail Packet Company, and of the Pacific Navigation Company,” as a “means of enlisting new friends” from among the captive audience of the ships’ passengers.[61]

Grubb’s biography, The Livingstone of South America (1932), was written two years after his death by a SAMS co-worker, Richard J. Hunt. Hunt joined the mission in 1894, accompanying Grubb in his work in the Paraguayan Chaco and in Argentina.

Grubb himself, however, is the subject of many writings in the genre of “missionary heroism.” Writing around the time Grubb stopped working in South America, Margarette Daniels included Grubb in a publication for the Missionary Education Movement of the United States and Canada, entitled Makers of South America (1916), alongside figures such as Francisco Pizarro, José de Anchieta, Simón Bolívar, Allen Gardiner, and Dom Pedro II. Two years before Grubb’s death, Sir James Marchant included him in a similar inspirational series entitled Deeds Done for Christ. Seeley & Company, who published Hunt’s biography, published children’s books on Grubb after his death. Based on one of these children’s books, the Baptist Board of Education (Southern Baptists, USA) included a booklet on Grubb in its three-part series of interactive and inspirational Christian missionary studies for use in the denomination’s “Royal Ambassadors,” a boys’ club similar to the Boy Scouts or the Knights of King Arthur. This literary tradition was continued in 1999 with a book on Grubb in a children’s Christian heroism series by Dave and Neta Jackson, alongside characters as wide ranging as Martin Luther, Harriet Tubman, and Gladys Aylward.

By Morgan Crago

Primary Source Bibliography

Grubb, W. Barbrooke. “The Chaco Boreal: The Land and Its People.” Scottish Geographical Magazine 16, no.7 (1900): 418-429.

—-. Un pueblo desconocido en tierra desconocida: Un relato de la vida y las costumbres de los indígenas lengua del Chaco paraguayo, con aventuras y experiencias de veinte años de trabajo pionero y exploratorios entre ellos. Asunción: Iglesia Anglicana Paraguaya, Centro de Estudios Antropológicos de la Universidad Católica, 1993.

—–. “The Paraguayan Chaco and Its Possible Future.” The Geographical Journal 54, no. 3 (1919): 157-171.

—–. “Mythology of the Guarayo Indians.” Folklore 35, no.2 (1924): 184-194.

—–. “The Yahgan Indians of the West Falkland Group.” Folklore 38, no. 1 (1927): 75-80.

Grubb also wrote numerous articles for the South America Missionary Magazine during the entire span of his service. This periodical is held at the Boston University School of Theology library archives on microfilm, and at the Church Missionary Society archives in digital form.

Commemorative/Inspirational Secondary Source Bibliography

Bedford, C.T. Barbrooke Grubb of Paraguay: The Story of His Great Work amongst Savage South American Indians and of His Many Adventures on Land and Water, told for Boys and Girls. London: Seeley Service, 1927.

Goldsmith, Merle. The Iron Arrow: W. Barbrooke Grubb. Roseville, N.S.W: South American Missionary Society, Australasian Association, 1983.

Jackson, Dave, and Neta Jackson. Illustrated by Julian Jackson. Ambushed in Jaguar Swamp: Barbrooke Grubb. Trailblazer Series. Minneapolis, Minnesota: Bethany House Publishers, 1999.

Marchant, James. Deeds Done for Christ. New York: Harper & Bros., 1928.

Murray, J. Lovell. A Selected Bibliography of Missionary Literature. New York: Student Volunteer Movement, 1912.

Other Electronic Sources

Phillips, Hannah. “’A Pioneer, I Presume’: The Life of W. Barbrooke Grubb.” Adam Matthew Digital. Published 18 December 2014. Accessed 5 May 2020. https://www.amdigital.co.uk/about/blog/item/grubb

Missiology.org.uk. Many of the books related to Grubb, including Hunt’s biography, are available here.

https://missiology.org.uk/blog/w-barbrooke-grubb-livingstone-south-america/

https://missiology.org.uk/blog/church-wilds-w-barbrooke-grubb/

https://missiology.org.uk/blog/barbrooke-grubbs-unknown-people-unknown-land/

Notes

[1] Robert Young, From Cape Horn to Panama: A Narrative of Missionary Enterprise among the Neglected Races of South America, by the South America Missionary Society (SAMS; Simpkin, Marshall, Hamilton, Kent & Co., 1900), 38.

[2] H.T. Morrey Jones, “Preface,” in An Unknown People in an Unknown Land (London: Seeley & Co., 1911), ix. The SAMS missionaries of the time referred to the Enexet tribe as the Lengua.

[3] Richard J. Hunt, The Livingstone of South America: The Life and Adventures of W. Barbrooke Grubb among the Wild Tribes of the Gran Chaco in Paraguay, Bolivia, Argentina, the Falkland Islands & Tierra del Fuego. (London: Seeley Service & Co Ltd, 1932), 91-92.

[4] In his address before the Royal Geographical Society in 1919, Grubb mentioned that he had “had the honour myself of representing the Paraguayan authority in the interior for some twenty-eight years.” “The Paraguayan Chaco and Its Possible Future,” The Geographical Journal 54, no. 3 (1919): 167.

[5] Young, From Cape Horn to Panama, 11, 14. It was not until 2010 that SAMS became a part of CMS. https://churchmissionsociety.org/about/our-history/south-american-mission-society-sams/

[6] South America Missionary Magazine 24 (August 1890): 182; South America Missionary Magazine (July 1893): 105.

[7] South America Missionary Magazine 30 (December 1896): 197-198.

[8] South America Missionary Magazine 30 (December 1896): 198.

[9] South America Missionary Magazine 27 (July 1893): 104.

[10] South America Missionary Magazine 24 (August 1890): 181.

[11] South America Missionary Magazine 24 (April 1890): 87.

[12] South America Missionary Magazine 33 (November 1899): 208-211.

[13] South America Missionary Magazine 42 (March 1908): 167.

[14] W. B. Grubb, “The Chaco Boreal: The Land and Its People,” Scottish Geographical Magazine 16, no.7 (1900): 423-424.

[15] Grubb, “The Chaco Boreal,” 423-424.

[16] Grubb, “The Chaco Boreal,” 424-425.

[17] Grubb, “The Chaco Boreal,” 426.

[18] Grubb, “The Chaco Boreal,” 427-428.

[19] Grubb, [Untitled Speech], in “Incidental Relations of the Missionary,” in Ecumenical Missionary Conference, New York, 1900, vol. 1. (New York: American Tract Society; London: Religious Tract Society, 1900), 332-333.

[20] Grubb, [Untitled Speech], 333.

[21]Grubb, [Untitled Speech], 332.

[22] D.S. Cairns, et al., The Missionary Message in Relation to Non-Christian Religions: Report of Commission IV (Edinburgh & London: Oliphant, Anderson & Ferrier; New York, Chicago & Toronto: Fleming H. Revell Company, 1910), 8.

[23] Cairns, The Missionary Message, 28.

[24] Cairns, The Missionary Message, 8.

[25] Cairns, The Missionary Message, 21.

[26] Grubb, “The Paraguayan Chaco and Its Possible Future,” The Geographical Journal 54, no. 3 (1919): 159.

[27] Grubb, “The Paraguayan Chaco and Its Possible Future,” 164.

[28] Grubb, “The Paraguayan Chaco and Its Possible Future,” 162-163.

[29] Grubb, “The Paraguayan Chaco and Its Possible Future,” 167.

[30] Grubb, “The Paraguayan Chaco and Its Possible Future,” 170.

[31] Grubb, “The Paraguayan Chaco and Its Possible Future,” 167.

[32] Grubb, “The Paraguayan Chaco and Its Possible Future,” 165-166.

[33] Grubb, “The Paraguayan Chaco and Its Possible Future,” 169.

[34] Even in cases where you can see concern or conflict between the lines, Hunt takes Grubb’s side. For instance, eventually one of the missions became a store and center of trade. “Trading was not, at that date, officially recognized by the society,” Hunt commented at one point, but Grubb thought it necessary “if the natives were to be protected from unscrupulous traders and the great lessons of business integrity and fair dealing were to be taught.” Later on, Hunt praised the “soundness of [Grubb’s] missionary methods” on the occasion that Grubb had urged SAMS not to send missionaries to Peru to protect local people from abuse in the rubber trade. Hunt, The Livingstone of South America, 164, 273-274.

[35] Hunt, The Livingstone of South America, 67.

[36] Hunt, The Livingstone of South America, 88.

[37] Hunt, The Livingstone of South America, 96.

[38] Hunt, The Livingstone of South America, 97. In a story Hunt includes about himself (not about Grubb), he did consider interacting with these diviners on their own terms. On one occasion, a brother of one convert, a “witch-doctor” named Manuel, challenged Hunt to pray for rain. Hunt conceded because “it was not a time to argue or to try to explain the principles of prayer to his untutored mind. From his view-point the statement was logical and well-expressed. God’s honor was at stake, so I quietly accepted the challenge, and asked God to vindicate His character and honour His Name before the people who had failed to get rain by witchcraft.” It rained within 2 days. Hunt, The Livingstone of South America, 154.

[39] Hunt, The Livingstone of South America, 291.

[40] Hunt, The Livingstone of South America, 105.

[41] Hunt, The Livingstone of South America, 217.

[42] Hunt, The Livingstone of South America, 111.

[43] Hunt, The Livingstone of South America, 129.

[44] Hunt, The Livingstone of South America, 201.

[45] Hunt, The Livingstone of South America, 67, 93.

[46] Hunt, The Livingstone of South America, 224.

[47] Hunt, The Livingstone of South America, 163, 288.

[48] Hunt, The Livingstone of South America, 164.

[49] Hunt, The Livingstone of South America, 202.

[50] Hunt, The Livingstone of South America, 210.

[51] Hunt, The Livingstone of South America, 253.

[52] Hunt, The Livingstone of South America, 283.

[53] Hunt, The Livingstone of South America, 286.

[54] Hunt, The Livingstone of South America, 287.

[55] Grubb, “The Indians of South America,” in “The Americas,” in Ecumenical Missionary Conference, New York, 1900, vol. 1. (New York: American Tract Society; London: Religious Tract Society, 1900), 481.

[56] Hunt, The Livingstone of South America, 208-209.

[57] Hunt does mention some friendly conversations between Grubb and a “witch-doctor,” but does not elaborate on just what Grubb learned in the exchange.

[58] Much of the article described the various challenges a person had to go through to reach the blessed place in the afterlife. Grubb makes only this one mention of Christianity in the article. Grubb, “Mythology of the Guayaro Indians,” 193-94.

[59] Cairns, The Missionary Message, 21.

[60] Hunt, The Livingstone of South America, 256-257.

[61] South America Missionary Magazine 39 (February 1905): 18; South America Missionary Magazine 39 (October 1905): 178.

Photos

Photo of W. B. Grubb taken from the front pages of Hunt, The Livingstone of South America (1932).

Photo of Mary Bridges Grubb taken from patbrit.org, “British Presence in Southern Patagonia,” https://patbrit.org/eng/intro/pbsite.htm