A protein produced by male embryos could someday treat ovarian cancer in women. While the idea may sound paradoxical, Patricia Donahoe, head of Pediatric Surgical Research Laboratories at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH), was sufficiently intrigued by the protein’s importance in embryonic development and its potential as an anticancer agent that she has dedicated more than 40 years to its study.

The protein is known as Müllerian inhibiting substance (MIS), and its primary job is to prevent the Müllerian duct, which is present in the embryos of all mammals, from developing into female reproductive organs in males. In the late 1970s, Donahoe (’58) hypothesized that MIS could inhibit the growth of tumors in tissues that develop from the Müllerian duct, including some of the deadliest ovarian cancers. She consequently founded the lab she continues to lead at MGH to study MIS and other areas of developmental biology that hold promise for improving patient care.

The quest to understand MIS has kept Donahoe, a former chief of pediatric surgery at MGH, engaged in research past typical retirement age. She still arrives at the hospital at 9:30 each weekday morning to begin a 10-hour day of working at the bench, writing papers and abstracts, critiquing experiments, and cultivating commercial partners. As a professor of surgery at Harvard Medical School, Donahoe also mentors postdocs and junior faculty and lectures to students in the health sciences and technology program, a collaboration between Harvard and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

“I love what I’m doing,” Donahoe says. “There’s a tremendous sense of mission in being able to take some of the things we’re studying in the lab as pure basic science and also seeking to apply them to the clinic.”

Allan Goldstein, the current chief of pediatric surgery at MGH, has known Donahoe since he was a pediatric resident at the hospital 25 years ago. “Pat teaches everyone around her the importance of passion,” Goldstein says. “She loves to talk about science. She’ll text you on the weekend because she thought of something. It’s just obvious that she really loves it.”

From Sports Standout to Surgeon

Donahoe grew up in a working-class family in the Massachusetts towns of Brookline and Braintree. “I was a good athlete,” she says. “I did every sport, every season, and then cheerleading every year in high school.”

She attended Sargent with the intent of becoming a physical education teacher. “But when I was studying human physiology, I became very enamored of science and medicine,” she says. “I had a fabulous teacher in physiology, Elizabeth Gardner, PhD, a beloved faculty member at Sargent. She would take me to the Harvard bio labs to hear great lectures by Nobel laureates, and that strongly influenced me to go to medical school.”

Donahoe taught physical education for two years at Indiana University while finishing her premed requirements, and then studied medicine at Columbia University’s College of Physicians and Surgeons, one of just six women, as she recalls, to graduate with the Class of 1964. She did her surgical residency at Tufts New England Medical Center, where she was the first woman to complete a chief residency in general surgery in Boston.

“As a surgeon,” says Goldstein, “she was totally committed to the patients and the families and was meticulous in her technical work in the operating room.”

“There’s a tremendous sense of mission in being able to take some of the things we’re studying in the lab as pure basic science and also seeking to apply them to the clinic.”–Patricia Donahoe (’58)

While raising three children, she was also breaking new ground in her research lab and carrying on a tradition that propelled MGH to the forefront of surgical correction of many birth defects in newborns, including tracheoesophageal cleft, a condition in which the trachea and the esophagus fail to separate as the baby develops in the womb, and diaphragmatic hernia, a rare condition in which babies have a defect in the diaphragm and associated, often lethal, lung hypoplasia.

Today, Donahoe’s lab is studying the gene defects that cause these abnormalities in hopes of developing drugs that can treat the conditions in utero. The lab is also working on a variety of clinical applications for MIS, including its use as a contraceptive, as an adjuvant therapy to increase the efficacy for in vitro fertilization, and as an agent to protect the eggs, or ovarian reserve, of women of reproductive age undergoing chemotherapy.

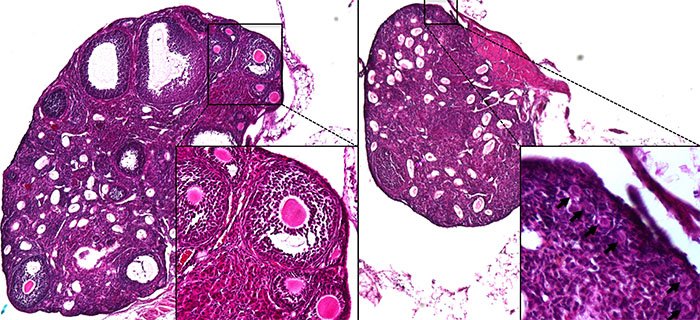

Throughout their decades of studying MIS, Donahoe and her colleagues have determined the locations in the body where the protein is produced and detailed the typical roles it plays in development. In addition to discovering MIS in the testes of male fetuses, where it influences sex differentiation, they’ve also found MIS in female ovaries and have begun studying its roles there. They have purified MIS, cloned its gene, and tested it as a treatment for several cancers in animals, where it has been highly effective. But they have yet to study its effectiveness in human trials.

Dogged Determination

To develop MIS as a drug for cancer or any other application, Donahoe needs a commercial partner who can make the protein in large quantities, and she has yet to find a pharmaceutical company to do it. “Big Pharma is hesitant to invest in the development of large complex proteins that are expensive to make,” she says.

Consequently, Donahoe’s lab is trying to develop what is called a “small-molecule mimetic” of MIS that copies the natural protein’s function in vivo but is smaller and therefore cheaper to produce. Despite the pharmaceutical industry’s reluctance, Donahoe maintains hope that MIS will eventually be used in combination with other drugs to fight cancer, as she envisioned it doing decades ago.

“She has dogged determination. You cannot change her focus,” says David Pepin, a Harvard assistant professor who began working in Donahoe’s lab as a research fellow in 2011. “She’ll work on something until she gets it done. She’s very fierce.”

Donahoe has trained hundreds of young surgeons and scientists. “It’s one of the joys of the job,” she says, and she has encouraged each of them to find a problem to sink their teeth into, as she has with MIS.

“It will keep them wanting to get up and go to work in the morning,” she says. “I think it’s so easy to burn out in medicine today if you don’t have something that excites you intellectually. Your science doesn’t necessarily have to be basic bench science. It can be anything, as long as you’re taking an unsolved problem and wrestling with it.”