Note: In this story, the author uses “autistic” and person-first language interchangeably. While some advocate for person-first language when referring to individuals with autism, many people with ASD prefer “autistic” as an embrace of their neurodiversity.

In 1943, eminent child psychiatrist Leo Kanner published a seminal report in the journal The Nervous Child detailing his observations of 11 children with remarkable intelligence whose behavior was “governed rigidly and consistently by the powerful desire for aloneness and sameness.” Kanner was among the first to describe the condition that would later come to be known as autism spectrum disorder (ASD), a developmental disability characterized by highly focused interests and marked differences in communication and social interaction. Although our understanding of autism has evolved significantly, much about ASD, including its causes, remains a mystery.

Autism cannot be diagnosed with a medical test. Instead, physicians and psychologists evaluate a person’s abilities and development. But as the word “spectrum” connotes, there’s no one profile for individuals with autism. People with ASD may exhibit a varied constellation of traits and behaviors that can make it challenging to treat. One autistic high school student may be headed for college with their typically developing peers while another is nonverbal. As autism researcher, author, and advocate Stephen Shore once said, “If you’ve met one person with autism, you’ve met one person with autism.”

Over the last two decades, autism rates have risen steadily in the US, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. In 2000, one in 150 children had a diagnosis of ASD by the age of 8. Today that statistic is 1 in 44. But experts say the jump in reported cases doesn’t point to a true surge. Rather, the increase can be explained by greater parental awareness, more routine pediatric screening, and a broadening of diagnostic criteria to include its milder forms.

With more and more families looking for answers and support, Sargent investigators and clinicians are at the forefront of some of the most innovative work in autism research and intervention. Emily Rothman, chair of the occupational therapy department, is devising new ways to support BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and people of color) youth with autism as well as those who are grappling with alcohol or substance abuse or who have been victims of sexual assault. (Read a Q&A with Rothman.) Gael Orsmond, who directs Sargent’s Families & Autism Research Lab, is studying ways to prepare autistic teenagers for adulthood. Basilis Zikopoulos, director of the Human Systems Neuroscience Laboratory, is pioneering research comparing the physiology of neurotypical brains to the brains of individuals with ASD. Simone Gill, director of the BU Motor Development Lab, is probing the connection between the way autistic kids move and how they think. Meghan Graham, a clinical assistant professor in the Department of Speech, Language, and Hearing Sciences, supports women with autism through a social group that embraces their neurodiversity.

“We still have so much to learn,” says Orsmond, who started her research with autistic individuals in the 1990s. “Back then we didn’t know much about autism, and in some ways, we still don’t. The complexity of autism requires that we all work together.”

Preparing for the Road Ahead

Gael Orsmond, associate dean of academic affairs and professor, occupational therapy

Gael Orsmond, director of Sargent’s Families & Autism Research Lab, has a knack for shining a light on blind spots in autism research. In 2017, she began interviewing autistic youth for The ROAD Ahead, a longitudinal study of academically capable high school students on the autism spectrum. Previous literature on young people with autism told a discouraging story about their transition to adulthood: they couldn’t get full-time jobs; they struggled in college; and they had trouble maintaining relationships. But that didn’t line up with what Orsmond was hearing.

“Almost all the youth [in our study] are working or are in postsecondary education, and they are largely satisfied with their social lives,” she says. Some of the discrepancy may be related to the abilities of this subset of autistic youth, but Orsmond believes previous measures of success were simply too binary. Working full-time and living independently were seen as good outcomes. But what if an autistic young woman was gladly living at home while taking part in a transition program to prepare her for college?

Orsmond developed more nuanced indicators for assessing productivity, social well-being, and autonomy within one’s living situation—indicators that consider a person’s satisfaction. “In our analysis, our young adults are doing very well,” she says.

Still, early data from Orsmond’s study point to the need for interventions focused on helping autistic youth strengthen executive functioning—higher-order cognitive processes that include working memory, planning, flexibility, and self-regulation—and social communication skills needed to manage daily life tasks. Orsmond hopes to develop programs that can motivate students with autism. “We know autistic youth don’t learn as much by observation,” she says, “so we need to explicitly teach these skills.”

Orsmond is spearheading another innovative project: helping families plan for when an autistic person’s parents or guardian can no longer provide support. “These are difficult conversations,” she says, and parents can be reluctant to burden siblings with caregiving responsibilities. “What often happens is, families don’t talk about it, and then a crisis happens,” leaving an autistic person without someone to support them in everyday life.

Orsmond and her colleague Kristin Long, an associate professor of psychological and brain sciences, recently completed the successful pilot of Siblings FORWARD, a program designed to help families of autistic individuals plan for the future. Through a series of telehealth sessions, siblings of autistic people received coaching on how to initiate tough conversations, set family goals, and navigate adult autism services. She plans to apply for another grant this year to expand the trial across other states. “Siblings know from a young age that they will play some type of role,” Orsmond says. “We want to empower them to have those conversations and share what they want.”

Variations, Not Deficits

Meghan Graham, clinical assistant professor, speech, language, and hearing sciences

When speech-language pathologist Meghan Graham (’06) started a group for women with autism in 2021, she brought together six of her clients with similar profiles. All were ambitious and highly capable—three had PhDs and most held demanding jobs—but, as a group, they struggled with executive functioning and navigating the social demands of their jobs. Graham believed she could offer valuable coaching to help them overcome these challenges.

But as the women began to share their stories, Graham found herself listening more than presenting. She was unsettled by how her clients had been mistreated in academic, professional, and even healthcare settings. One woman’s boss told her, “You’re smarter than you are annoying, thankfully.” Another woman, a talented data analyst, was deluged with criticism from her team. “The way this woman can see patterns in the data is remarkable, yet all she gets is negative feedback for her communication style,” Graham says. “These women have amazing gifts that are often not appreciated because they don’t fit the typical mold. Hearing how misunderstood they are was heartbreaking.”

It was also revelatory. Graham was struck by how, despite their troubles at work, the women understood one another perfectly when they were together. It wasn’t that her clients were poor communicators, she realized. They were simply speaking a different dialect. “I started taking more of a neurodiversity approach,” Graham says—one where differences in ways of thinking and behaving are seen as variations, not deficits.

“I’m unlearning everything I thought I knew about how to treat autism,” she says. “It’s not about teaching these women how to act more like the rest of us. I see my role now as helping them understand their own profiles as well as sharing what the neurotypical experience and expectations are, because that’s the majority of the world they’re living in.”

Mostly, Graham says, it’s about creating community and building self-advocacy skills. Last month, the group generated a flyer about what it’s like to be a woman with autism and shared it with coworkers. It was so well received that they’re now working on launching a website.

“The way our society approaches people with autism is biased in many ways. We make it so that neurodivergent people have to conform to our [neurotypical] social frameworks, and they shouldn’t have to,” Graham says. “We should be teaching about these differences and giving people the autonomy to advocate for what they need.”

A Move Toward Better Interventions

Simone Gill, associate professor, occupational therapy

As director of BU’s Motor Development Lab, Simone Gill spends her days studying how children and adults move through the world. She has examined how obesity impacts a person’s gait and whether body composition affects motor performance and cognitive functioning.

In 2018, Helen Tager-Flusberg, director of BU’s Center for Autism Research Excellence and a mentor to Gill, proposed they do a joint study on minimally verbal children with ASD. The working assumption is that these children have cognitive impairments that impede language development. But what if there is a physical component, too?

The study piqued Gill’s interest in exploring the relationship between gross motor function and cognitive development in kids with ASD. “Autistic children tend to sway when they stand and have less postural control,” she says. This makes them less apt to engage in physical activity, such as playing tag at recess or climbing a jungle gym. “Yet we know for all kids, especially those with autism, engaging in group activities spurs growth in cognition and social interaction—things like turn taking and reading nonverbal cues. All of these things are very much related.”

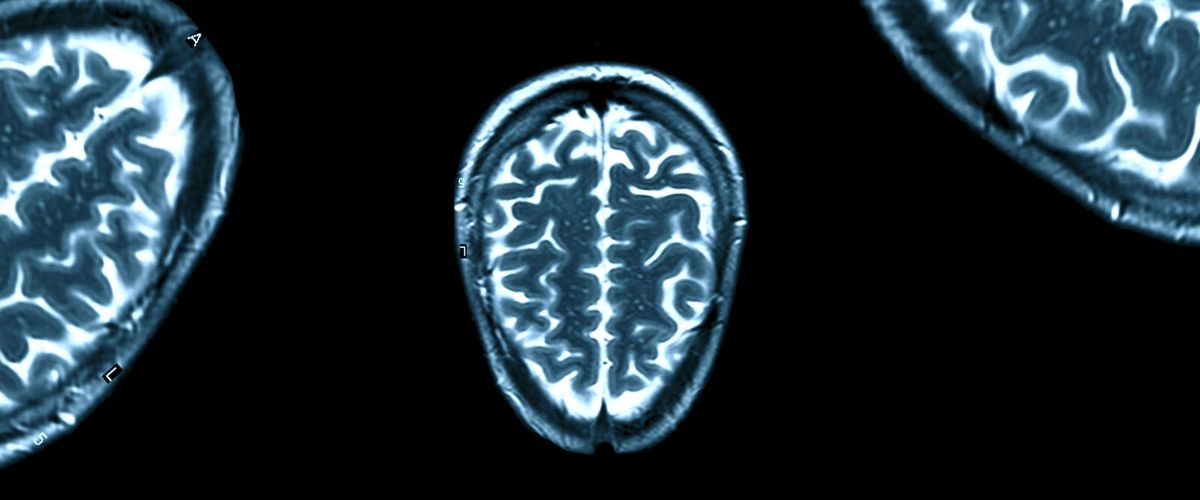

Gill has applied for a grant from the National Institutes of Health to study the neural basis of motor function in kids ages 7 to 12 with ASD. The proposed study would recruit 60 children—30 who are typically developing and 30 who fall across the range of the autism spectrum. Gill plans to compare brain scans taken while the children perform physical and cognitive tasks, particularly ones that involve competition between the two: keeping balance and talking at the same time or completing a categorization exercise on a touch screen while balancing on one leg, for example. “Having them perform dual tasks will expose challenges related to both,” she explains. (Gill plans to collaborate with David Boas, a BU professor of biomedical engineering and an expert in functional near-infrared spectroscopy, a groundbreaking technology that allows neuroimaging to be done while a subject is moving.)

“Perhaps we can find new interventions that give us more bang for our buck—ones that improve both motor function and cognitive development at the same time,” Gill says. “My hope is that what we learn will help us move toward creating personalized, innovative interventions for children with autism.”

A Window into the Brain’s Circuitry

Basilis Zikopoulos, director, Human Systems Neuroscience Laboratory

Fifteen years ago, when Basilis Zikopoulos was still a research associate in BU’s health sciences department, working with BU neuroscientist Helen Barbas, he received a profound gift from a colleague. Gene Blatt, then a neurobiologist at BU’s School of Medicine, gave him samples from two postmortem human brains donated from individuals with autism and matching control tissue. The tissue samples enabled Zikopoulos to conduct a series of pilot studies that led to securing his first-ever grant—to study white matter cortical pathways in autism—and launched his career as a neuroscientist.

“A human brain is the most precious resource you could ever ask for,” says Zikopoulos, now an associate professor in health sciences. Today, his tissue bank contains nearly 100 postmortem brain samples from child and adult donors, with and without autism or other brain disorders. Specially cryopreserved and processed, the tissues can last for decades.

Most autism research centers on the functioning and behavior of living subjects. Zikopoulos’ access to human brain tissue gives him a unique window into the neural circuitry—and even molecular inner workings—of developmental disorders such as autism and schizophrenia. “It’s amazing to be able to understand exactly how different neurons connect and communicate with each other at the structural and molecular level,” he says.

Using high-resolution microscopy and advanced imaging and computational approaches, Zikopoulos is breaking ground on an avenue of research that explores the anatomical and physiological basis of neurodiversity. “We are the only lab in the world that has shown specific structural and molecular changes in the individual axons in brains of people with autism,” he says. “We have identified specific markers and growth proteins that can give us clues about how and when disorders like autism develop. Once we understand the pathology of these networks and pathways, we can be more targeted in our approaches to treating people with autism.”

In addition, Zikopoulos and Barbas, a professor of health sciences, have spent years working together to map the cortical pathways of rhesus monkey brains, yielding critical clues about the possible organization of human brain networks. With the additional help of BU computational neuroscientist and close collaborator Arash Yazdanbakhsh (GRS’05), a research assistant professor, the team is building a digital brain that can be used to simulate human brain activity. “Through these models, we can start disrupting nodes and processes in the network and begin to understand which mechanisms might play a key role in various disorders.”

A prolific investigator with several papers currently under review and more in the pipeline, Zikopoulos is brimming with new ideas. “Every time we answer a question, we have at least two or three more we want to answer,” he says. “It’s a never-ending process, but it’s very exciting.”