CHEF SERIES – On the Rise: Getting to Know Your Leaveners

Jessica Spier, Graduate Student in Dietetics, SAR ’17

For a sandwich, as a side, or served up as morning toast, there are so many different types and times that we enjoy bread. Thinking about lofty, fluffy, leavened loaves, there are two leaveners in particular most highly debated for baking the best bread: yeast vs. sourdough. So which bread starter is best? It depends!

First, let’s meet the contenders…

Yeast

These microscopic, single-celled, oblong, fungi feed on sugar. Baker’s yeast is called Saccharomyces cerevisiae, or “sugar-eating fungus.” Ever read a recipe including yeast and note the specific temperature of the water to be mixed in? It’s for the yeast! Just warm enough to be active, but not so warm as to cause harm.

Yeast facilitates fermentation, that is the transformation of carbohydrate into ethyl alcohol while releasing carbon dioxide as a byproduct. In bread making, yeast ferments carbohydrates in the recipe’s required flour and sugar, giving yeast-leavened breads their typical flavor and aroma, and all the while crafting carbon dioxide gas. This CO2 produced is unable to breach the bread dough’s elastic matrix, but, of course, dough can stretch, expand and inflate with increased volume of gaseous byproduct. The result? Rise! It’s the how and why the dough ball you put into the oven emerges a voluminous loaf of bread.

Sourdough

Sourdough is already fermented; it’s a step along the fermentation process rather than an initial ingredient. It mimics yogurt making where each time you make a batch you hold back a portion to be used as the starting culture for the next pot. Why? It saves you from having to repeatedly buy the starting culture (or yeast), and it’s famed for evolving and deepening flavor over time.

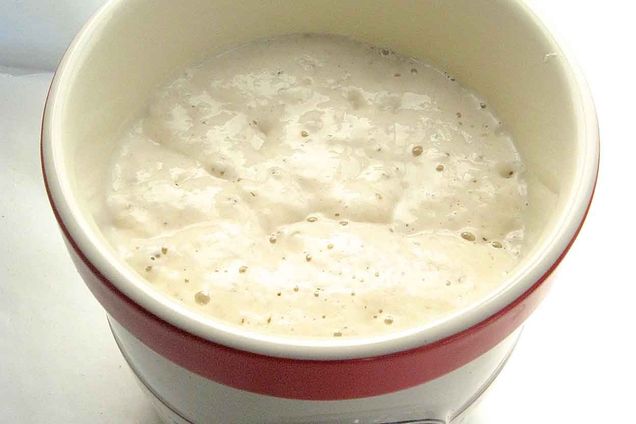

Sourdough starter is simply a mixture of flour and water left to it’s own devices to become the medium for wild yeasts and lactobacilli that exist in our environment. Fed with more flour and water during the process of making bread dough, the sourdough coaxes the same leavening from the dough as would yeast. It is, however, an acid fermentation process instead of the alcohol fermentation carried out by S. cerevisiae. These sourdough tiny lactobacilli convert carbohydrates to lactic acid in this dough, and again with carbon dioxide production as a byproduct. The result? A bread with that hallmark, mildly sour taste that you don’t find in yeast-leavened loaves. Oh, and again, a lofty rise.

The great thing about sourdough starter is that it doesn’t require purchase of yeast; you always have the sourdough just ready to go. But, it’s also a living, breathing, bread starter colony, so it comes with some responsibilities.

My favorite description of the sourdough starter comes from an article in the New York Times Food Section: “A sourdough starter comes into your life the way a turtle might: as a pet you maybe didn’t know you wanted until someone hands it to you or you find yourself holding the terrarium after an impulse purchase you couldn’t explain if you tried.”

A sourdough starter isn’t just an ingredient, it’s a commitment; it requires attention, and food in the form of a consistently scheduled supply of flour and water. Some people even name theirs, although that’s more of a personal preference.

So, if you’re adding more ingredients to the starter, doesn’t that mean it will grow? Yes! Never a problem for the restaurant kitchen that siphons off starter to bake loaves in mass quantity, or the at-home cook devoted to fresh bread baking on a weekly, if not daily, basis. But, yes, to avoid a starter from taking over likely limited real estate on your kitchen counter, the commitment to bake, and bake, and bake some more, is required.

There is good news! Still interested in kicking off a sourdough starter but not certain you can keep pace with the growing culture on your counter? You can put it in the refrigerator to slow starter metabolism. This option allows you to feed and use the sourdough much less frequently. The King Arthur Flour feeding guide recommends keeping the starter in a ceramic crock in the refrigerator and feeding it once weekly with scant 1 cup of flour (any flour of your choice—whole wheat, buckwheat, the list goes on!) and ½ cup of water.

So, yeast or sourdough? The choice is up to you. You might find you prefer the distinct flavors and aroma of one over the other, or that you prefer the convenience of cultivating sourdough instead of buying yeast for each batch, or that you prefer the easy storage of yeast compared to the finicky sourdough feeding schedule. Or maybe bread baking at home now sounds entirely overwhelming, but you can use your new knowledge of yeast vs. sourdough to better enjoy every bite of your favorite bakery breads for their yeasty, or sour, flavor and fluff.

Jessica Spier is a current graduate student at Boston University, receiving her MS in Nutrition at Sargent College with intent of becoming a Registered Dietitian working in the Boston community. She holds a BA in English and Spanish languages and literatures from Skidmore College, and a food studies certificate from BU’s Gastronomy program. Jessica attended culinary school through Metropolitan College’s Food & Wine program and has staged at several Boston area restaurants. Currently, Jessica works as a chef and culinary instructor for Cooking up Culture, BU’s cooking program for 1st-12th grade kids, where she teaches culinary skills and techniques for balanced, healthy eating through exploration of diverse flavors and cuisines. Jessica completed her practicum at the Sargent Choice Nutrition Center in spring of 2016.