Privately Public: D. Appleton and Co.’s Artistic Houses (New York, 1883-4)

If a portrait photograph can capture the likeness of a person in both appearance and character, so too can a photograph of an interior, such as those that appear in Artistic Houses, preserve both the form and feeling of a room. Published by D. Appleton and Company of New York in two volumes, each comprising two parts with 203 plates total, Artistic Houses was printed in a limited run of five hundred copies for preselected subscribers in ten sections over a two-year period between 1883 and 1884.[1] The subscriber’s name appears printed on the secondary title page of volume 1 part 1 of each numbered copy as a personalized supplement to the half-title leaf in black and red type (Fig. 1).[2] Lest we be fooled by the book’s printed publication into thinking it was widely available, we should understand the audience of patrons that constitute the readership, or rather ownership, of Artistic Houses as private. The interiors photographed, the photographs themselves, and the publication as a whole were highly controlled in design and distribution according to the combined ambitions of the publisher, author, photographer, and owners.[3] Predetermined in form and function, Artistic Houses maps the people and things propelling America’s Gilded Age by and for a particular public.

Though explicitly identified, the network of people by and for whom Artistic Houses was published is largely unacknowledged by scholars who focus on individual collections and collectors. Subtitled Being a Series of Interior Views of a number of the Most Beautiful and Celebrated Homes in the United States with a Description of the Art Treasures contained therein, the series is assumed to have been authored by George William Sheldon with photographs by the highly respected Gutekunst Company of Philadelphia.[4] Frederick Gutekunst gained notoriety during and after the Civil War as a portrait photographer and official photographer of the Pennsylvania Railroad, staking his reputation on the quality, reproducibility, and purported truth-value of his images (Fig. 2).[5] Gutekunst understood the unique demands of both portraiture and landscape, making him a fitting photographer for Artistic Houses, itself a project that posits each interior as a kind of panorama portrait in miniature, both in terms of scale and traversability.[6]

The interiors featured in Artistic Houses were selected to represent “the triumphs of contemporaneous American interior architecture and decoration,” according to the ambitions of the author, photographer, and publisher responsible for the volumes, as well as the owners whose interiors were showcased therein.[7] They were created, reconstructed, or refurnished around the same time and betray a decorative coherence if not conformity. Designers guaranteed homeowners fashionable rooms reflecting their wealth and status in an idiom where copying was not just a form of flattery but a way of demonstrably fitting in. Of the ninety-seven buildings photographed for Artistic Houses, ninety-three were private homes, 96 percent of whose interiors were spaces in which the family met or entertained selective audiences.[8] The chosen interiors publicize points of pride, not practicality, to prove the author’s contention that the nation’s domestic architecture was unrivaled for its trophies of “original, affluent, [and] admirable” achievement.[9] These spoils are easily spotted to sustain individual narratives of success. For example, the emphatically exposed light bulbs in Mr. J. Pierpont Morgan’s drawing room, library, and dining room remind us that his home was the first in New York to be electrically lit (Fig. 3). This practical luxury signals wealth and power: Mr. Morgan was able to illuminate various rooms instantly and remotely by turning a knob.[10]

Presented in miniature, photography condenses the interior and its many objects such that they may be (re-)possessed, as Gaston Bachelard promises in his Poetics of Space: “the cleverer I am at miniaturizing the world, the better I possess it.”[11] In an era of rapid economic and industrial growth, urban pockets of American individuals amassed great fortunes often quantified by carefully calculated private collections displayed in deliberately designed interiors. The rooms photographed for Artistic Houses encapsulate self-contained expressions of power, taste, and style that constitute a crucial material part of the American Gilded Age. The staged photographs maintain and miniaturize these interiors, redoubling the conscious self-fashioning of these celebrated spaces for an equally considered and circumscribed audience. When we hold these homes in our hands and walk through their rooms by turning the pages of Artistic Houses, we witness publishing strategies similar to those at play in the creation of the interiors themselves.

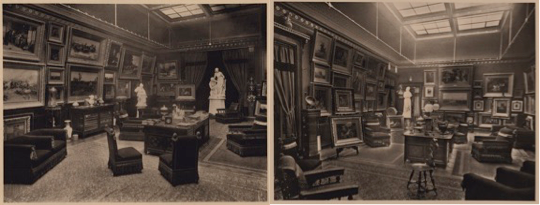

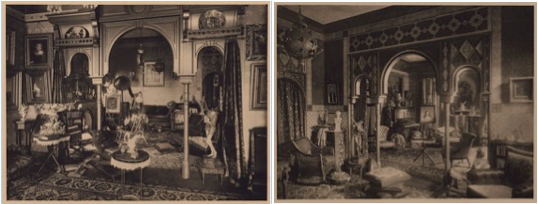

Two pairs of photographs in particular measure the extent to which rooms were readied for photographing. John T. Martin’s picture gallery and F. W. Hurtt’s library were both photographed and published from two different vantage points, which through comparison reveal purposeful inconsistencies. Martin’s prized painting, Going to Work, by Jean-François Millet (Fig. 4), is seen in the photograph titled “Mr. John T. Martin’s Picture Gallery” behind the divided sofa at the near left, and in the following photograph, the “second view,” on the easel at the distant right, so as to include the canvas in each view (Fig. 5). Similarly, in the Hurtt interiors, the statue of a strumming musician appears in the foreground room of two distinct photographs. Although occupying the same liminal space between library and parlor, the sculpture is oriented to face us, the reader and intruder, in each view (Fig. 6). This multiplicity of images, therefore, aims to reconcile the insufficiency of a single point of view while retaining the owner’s most prized possession in each.

Because Artistic Houses was distributed to presecured buyers, the publisher did not need to advertise or garner favorable reviews to prompt profits. Accordingly, there are few contemporaneous published references to Artistic Houses, an absence understood rather as an insurmountable difficulty, explained in part by the frustrated editor of Art Age in May 1883, “Their method of selling works, however, prevents any but a very few privileged persons from becoming acquainted with them, and were it not for special concessions, the plates from their last work, “Artistic Houses,” of this country would not be given here, owing to the sedulous care with which any information concerning the work is kept from all but the canvasser in charge of its sale.”[12] Despite it’s premise and promise of accessibility, Artistic Houses was made available only to a precious few.

Artistic Houses allowed an exclusive number of preselected subscribers to hold the interior in miniature, to walk through rooms by turning the page, to experience private spaces made public. Each room, like each page, is simultaneously a total work unto itself and part of a larger whole. Taken together, the text and photographs provide a particular path through which to navigate the chosen space, taking note of the furnishings, objects, materials, and styles called out to the author by the owner.

Itself a container for the contained, Artistic Houses is a self-serving celebration of American Gilded Age self-fashioning, printed lavishly in small number for a limited, like-minded audience. Considered in the context of ownership, rather than readership, Artistic Houses is an object among many in the very crowded interiors it collects. This bound cultural object functions reciprocally and redundantly for the home in which it is housed. And though there are no people pictured, the photographs function synecdochically for the very inhabitants intimated but never seen.

Kathryn Kremnitzer

[1] D. Appleton and Company secured the publication’s copyright in 1882, having published Picturesque America and Picturesque Europe in the previous decade. The New American Cyclopedia, published in sixteen volumes from 1857 to 1866, had made the Company world-famous.

[2] No. 85, now in the collection of the Cooper-Hewitt Smithsonian Design Library, can be accessed digitally online at http://library.si.edu/digital-library/book/artistichouses1. I am in the process of finding and cataloguing extant copies.

[3] The featured interiors were probably chosen by the author, with the owner’s consent, and ultimately approved by the publisher.

[4] George William Sheldon’s name does not appear on the title page of Artistic Houses or anywhere else in the publication. Sheldon is identified as an “author of several works of art” in his New York Times obituary (January 30, 1914, p. 9), which names him as author of several publications published by D. Appleton and Company, including “Artistic Homes [sic.].”Arnold Lewis, James Turner, and Steven McQuillin, The Opulent Interiors of the Gilded Age. New York: Dover, 1987, v-vi.

[5] Michael Froio, “Preserving the Legacy of the Pennsylvania Railroad,” http://michaelfroio.com/blog/2015/03/24/preserving-the-legacy-of-the-pennsylvania-railroad. Accessed August 15, 2016.

[6] In 1878, Gutekunst purchased the rights to a photomechanical process, which would allow for the mass production of high-quality reproductions of photographs, such as the phototypes published in Artistic Houses. Frank Hamilton Taylor, The City of Philadelphia as it appears in the year 1894. Philadelphia: G. S. Harris & Sons, 1894, 220.

[7] [George William Sheldon], Artistic Houses: Being a Series of Interior Views of a Number of the Most Beautiful and Celebrated Homes In the United States, with a Description of the Art Treasures Contained Therein … New York: Printed for the subscribers by D. Appleton and company, 1883, volume 1, part 1.

[8] Steven McQuillin, Arnold Lewis, James Turner. The Opulent Interiors of the Gilded Age: All 203 Photographs from “Artistic Houses,” with New Text. New York: Dover Publications, 26.

[9] “Explanatory Note,” Artistic Houses, 1883, volume 1, part 1. Artistic Houses ignores basements, bathrooms, bedrooms, attics, kitchens, servants’ quarters, and service areas essential to the household’s maintenance as inhabitable and hospitable. The text similarly pays little attention to the exterior and plan of the house.

[10] Artistic Houses, 1883, volume 1, part 1, 80.

[11] Gaston Bachelard, The Poetics of Space, trans. Maria Jolas. Boston: Beacon Press, 1969, 150; Sarah Anne Carter, “Picturing Rooms: Interior Photography 1870-1900,” History of Photography, 34, 3 (2010): 252.

See also the 12-page publication accompanying 1984 exhibition “A Photographic Intimacy: The Portraiture of Rooms, 1865-1900” which proposes that there is “a cryptic portrait in the furnishing and arrangement of domestic rooms, simultaneously revealing intimate traces of personal taste and habit, but also concealing them with the inscrutable layering of fashion and style.” Ellie Reichlin, A Photographic Intimacy: The Portraiture of Rooms, 1865-1900. Cambridge: New England Foundation for the Arts, 1984.

[12] Arthur B. Turnure, ed., Art Age, May 1883, 10.