Dreamlands: Immersive Cinema and Art, 1905–2016

Dreamlands: Immersive Cinema and Art, 1905–2016

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

October 28, 2016 – February 5, 2017

In the ambitious and stimulating exhibition, Dreamlands: Immersive Cinema and Art, 1905 – 2016, the Whitney Museum of American Art continued to flex its curatorial muscles thanks to its adaptive and technologically proficient galleries designed by Renzo Piano. Surveying artistic experimentation with moving images since the invention of film technology at the dawn of the twentieth century, with forty works and installations by thirty-eight artists (not including the extensive list of theater screenings and expanded cinematic events off-site), curator Chrissie Iles installed a remarkable breadth and variety of works throughout the museum’s record-sized fifth-floor gallery.

In several ways, the exhibition’s title is a misnomer. Iles is not solely working with cinematic works or the legacy of cinema, nor are works exclusively immersive in an embodied sense. The title’s words, instead, served to point towards the exhibition’s exploration of the subjective conditions engendered by moving images as a way to “articulate technology’s dramatic influence on how we see and experience the world,” according to Iles. We cannot criticize the exhibition’s gaps in chronology or omissions of artists and genres within this seemingly inclusive framework, once we recognize that Iles’s selections stem from a focus on artistic challenges to the conventions of conceiving, producing, and experiencing moving images.

In this regard, the show’s moments of stillness stood out. Almost hidden along the gallery’s eastern bank of windows, Alex Israel’s massive painting, Sky Backdrop (2016), unexpectedly presented viewers with stasis. Derived from hand-painted scenic scrims of Hollywood studio films, Israel’s painting extends the notion of the cinematic to an extreme, engaging it through scale and aspect ratio, creating a physical relationship approximate to that of the enveloping screen of the cinema. Works like this, whose own stillness belie any immediate relation to the cinematic, hinted that the exhibition missed an opportunity to be something much more than an accumulation of film and video installations. Yet, worth recognition were sculptural and cybernetic works such as Lynn Hershman Leeson’s DiNA (2004-06) and Dora Budor’s Adaptation of an Instrument (2016), which reacted visually and kinetically to audiences’ spoken and physical input. In Budor’s sensing and responsive environment, our bodies’ movement elicits pulsating lights modeled on neurological pathways, while Leeson’s cyborg/chatbot software immerses participants’ voices and subjectivities within the omnipresent cyberspace of the Internet.

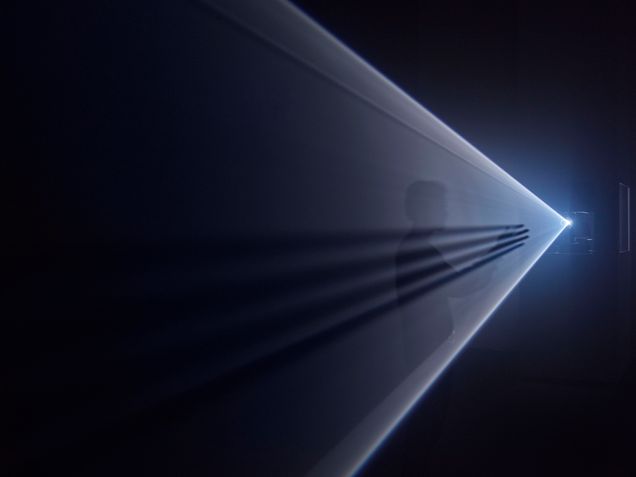

However, the utter diversity of works on display, which spanned from early-twentieth-century animators and filmmakers, like Oskar Fischinger, to mid-century Expanded Cinema pioneers, like Anthony McCall, betrays the exhibition’s medium specificity. What unites these artists of diverse historical-political contexts and works of dazzlingly distinct content? Largely moving images, novel uses of technology, or more explicit allusions to traditional Cinema (seen in the Disney Studio Artists sketches of Fantasia and Syd Mead’s gouache renderings for Blade Runner), yet such links often felt tenuous, even arbitrary. Nevertheless, it seems productive to willfully juxtapose works of Expanded Cinema, Video Art, and New Media, to name a few categorical distinctions, in order to understand the interrelations between technology and subjectivity and bypass the usual discursive boundaries that isolate these works. But this roughly chronological, labyrinthine, and practically context-free journey through “immersive cinema” did not resolve, or synthesize, the larger stakes of artists’ perennial union of imaging technologies and art. The show’s variety undermined the critical potentials of many of its strongest individual works, such as Frances Bodomo’s afrofuturist film and Leeson’s techno-feminist media. Nonetheless, Dreamlands immersed audiences in superb installations that testify to the increasingly embedded and synesthetic relationship between technology and human subjectivity.

William Schwaller