La Marchande d’Amour : The Commodification of Flesh and Paint

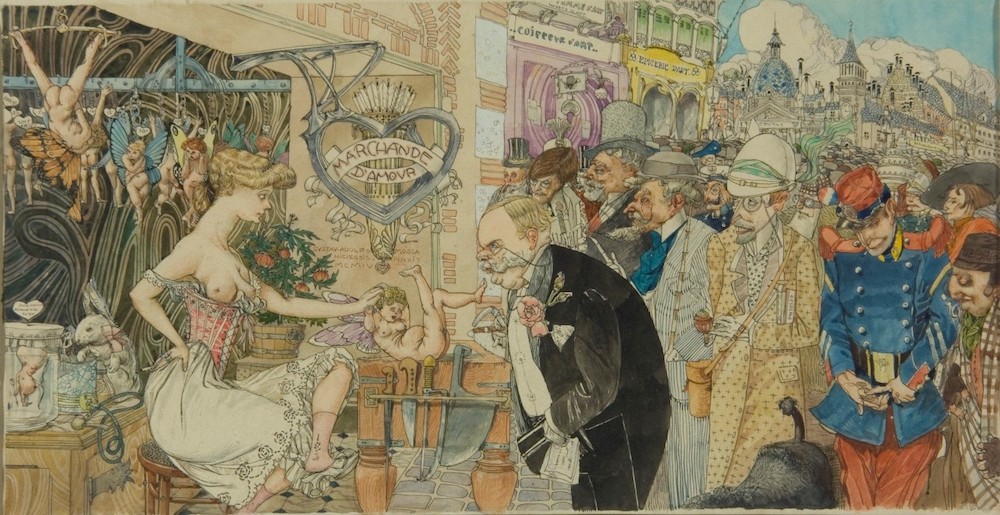

Niçois watercolorist and oil painter, Gustav Adolf Mossa (1883-1971) exaggerated and satirized popular nineteenth-century motifs by coating his compositions with caricature. In turn, his oeuvre is slippery, referencing multiple—even conflicting—styles and tropes especially evident in the watercolor La Marchande d’Amour (1904) (Figure 1). Mossa crowds La Marchande d’Amour with references ranging from classical subjects to stereotypical modern masculine types with a critical and comical wit. His multilayered pastiche satirizes artistic production, comparing it to the commodification of flesh enacted by a Venus-like merchant who butchers and sells female cupids to a sea of waiting male customers. By comparative analysis, I will argue that Mossa’s complex layering of recognizable artistic motifs, including classical iconography and modern types, supports a self-reflexive interpretation of the production and commodification of art as akin to prostitution.

La Marchande d’Amour is a critical reinterpretation of a centuries-old motif, which shaped romanticized neoclassical aesthetic preferences. When the ancient Cupid Seller fresco was discovered during the excavation of Pompeii between 1748 and 1763 (Figure 2), it inspired Joseph-Marie Vien to paint one of the earliest French neoclassical works, likewise named The Cupid Seller (Figure 3).[1] Lauded as a return to the true ancient arts, Vien’s painting inspired everything from cupid seller-themed fabric designs to marble reliefs (Figure 4). Print reproductions of the ancient fresco and Vien’s neoclassical adaptation were widely distributed, further establishing the cupid seller motif as part of the public’s visual vocabulary.

Where Vien’s popular eighteenth-century version of The Cupid Seller omits erotic subtleties included in the classical Roman original, such as a peeping cupid from between the woman’s legs, Mossa responds with an unabashedly sexualized reinterpretation. Instead of reiterating the traditional exchange of cupids sold between females and staged in a private setting, Mossa’s commercial merchant sells decidedly female fairy-like cupids to a range of typed European and colonial male consumers, emphatically reinterpreting the motif in terms of commodified female bodies, and more precisely prostitution. The international crowd and Parisian locale, registered by the “Batignolles” sign in the distant background, alludes to the Exposition Universelle that Mossa attended in 1900; but instead of perusing the world’s showcases of art and technology, Mossa’s crowd is lured toward the Marchande d’Amour.[2] By situating the theme in a modern context, Mossa collapses the distance between classical allegory and modern reality, transforming the trope from the source of a classical revival of “true art” into a criticism of artistic commodification.

Nineteenth- and early twentieth-century artists and art critics frequently alluded to the era’s ruling Venus, the prostitute, when discussing the commodification of aesthetic labor. Émile Zola exemplified the ease with which writers compared prostitution to artistic practice. In response to the shocked public reception of the then-scandalous Olympia, he defended Édouard Manet by satirizing the public’s reaction as akin to that of prostitution, saying “the arts, painting, is for them the great Impure, the Courtesan who is always famished for young flesh.”[3] Moreover, he addresses the public perception that art disrupts domesticity by jokingly calling it “the orgy, debauchery without pardon, the bloody specter that from time to time raises itself within families and disturbs the peace of domestic homes.”[4] Zola leveraged prostitution’s threatening preeminence to satirize the comparatively unaccountable threat felt toward artworks such as Manet’s.

As Leo Bersani has persuasively argued, Charles Baudelaire also compared art with prostitution to communicate their shared potential to navigate the interstices between love and desire, spirituality and extra-bodily experience, and power and vulnerability.[5] In his squibs on the nature of art and prostitution, Baudelaire wrote, “What is art? Prostitution,” alluding throughout Journaux Intimes that artistic exchanges require the giving up of oneself to another.[6] Likewise in La Marchande d’Amour, Mossa leverages the familiar analogy for his own purposes, underscoring comparatively exploitative systems of commodity exchange that place the sale of one’s aesthetic labor on par with the sale of one’s body.

Further entangling this association, Mossa literally inscribes commercialized prostitution in the artistic language of the signposts and texts throughout the painting. Purposefully naming the merchant’s neighboring stores “coiffeur d’art” and “épicerie d’art,” these art-hairstylists and art-grocers textually situate La Marchande d’Amour, a prostitute or madam, as complicit in the production of artistic commodities. Mossa also inscribed “HORS CONCOURS / MEDAILLE D’OR / EN 1900” in bold black ink on a heart-shaped tag atop the preservation jar of a dead fetal cupid. The phrase “hors concours” was and is often used in art exhibitions to designate artwork submitted for exhibition, but not for competition or without competition. Significantly, “hors concours” often identifies works that are overqualified and therefore disqualified. It connotes that the work is unrivalled. Mossa assigns the classical male cupid an “hors concours” nomenclature and carefully preserves him in a reliquary. Rather than subjecting him to the butcher block like the entrapped female cupids, Mossa establishes a binary between what is and is not of social and aesthetic value. In this case, the valued or protected object is the classical male cupid while the female body is exploited to meet consumer demand.

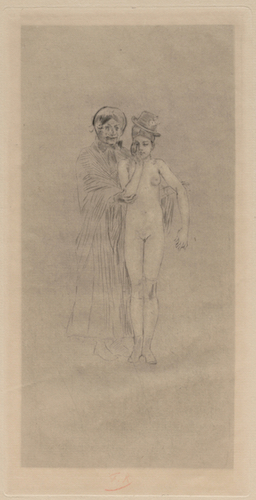

As in Mossa’s La Marchande d’Amour, Felicien Rops used language to pointedly criticize the art market, particularly in his print entitled Ma Fille, Mr Cabanel (Figure 5). Rops portrays an older woman offering to the viewer a young naked girl who shamefully hides her face beneath her raised hand. The faintest indication of socks and the bonnet on her head magnify her naked body in contrast to the heavily garbed madame, who wears a hat and is cloaked in a shawl and long dress. The provocative title, “Ma fille,” a phrase of endearment meaning “my daughter,” works against expectations of a protective mother who instead presents the girl’s body for the viewer’s consumption. Rops ties this antagonism to a specific consumer named Alexander Cabanel, a prominent Salon figure known for historical and mythological paintings featuring highly sensualized female nudes. For instance, his La Naissance de Venus (1863) depicts a suggestively postured, newly born Venus floating on seafoam.[7] The painting received a great deal of admiration, but Zola argued that Cabanel’s Venus might offend were she not “cradled in classical diapers,” drawing attention to Cabanel’s classicism as thinly veiled sensuality.[8] Ma Fille, Mr Cabanel produces similar accusations through the language of prostitution. As Mossa uses language, specifically “hors concours,” to evoke the Salon’s privilege for assigning aesthetic value, Rops accuses Cabanel—and by association the Salon—of producing a system that is nothing more than veiled prostitution.

Responding and contributing to contemporary writers’ and artists’ prostitution-themed vocabulary as a means to critique the Salon and art production in general, La Marchande d’Amour entangles art with prostitution. Mossa situates the commodification of paint and flesh in a conversation that effectively amplifies the role of the market’s morally complicit consumer, the hungry international crowd willing to purchase anything marketed as art. The consequence of their pleasurable commodities, as Mossa effectively argues, is the demise of lesser bodies entrapped by the system—female prostitutes and, by analogy, artists. By glossing the classical Cupid Seller theme with satiric language and situating the merchant’s store amidst artistic shops, he engages the visual language of the modern Venus-prostitute. Thinly veiled in a classical trope, she sells bodies instead of art as a comparison to the commodification of the art world.

Cortney Anderson Kramer

_______________________________________________________________________

[1] Thomas W. Gaehtgens and Russell Stockman, “‘Love Fleeing Slavery’: A Sketch in the Princeton University Art Museum,” Record of the Art Museum, Princeton University 65 (2006); 14.

[2] Richard Thomson, “Fantasies and Allegories of Vice,” in Splendours & Miseries: Images of Prostitution in France, 1850-1910, ed. Richard Thomson et al. (Paris: Musee d’Orsay, 2015), 211.

[3] Émile Zola, Éd. Manet: Étude biographique et critique accompagnée d’un portrait d’ Éd. Manet par Bracquemond et d’une eau-forte d’Éd. Manet d’après Olympia (Paris: E. Dentu, 1867), 13. Original French: “mais les arts, peinture eft pour eux la grande Impure, la Courtisane toujours affamée de chair fraiche, qui doit boire le sang de leurs enfants & les tordre tout pantelants sur sa gorge insatiable.”

[4] Ibid., 13. “Là eft l’orgie, la débauche sans pardon, le spectre sanglant qui se dresse parfois au milieu des familles & qui trouble la paix des foyers domestiques.”

[5] Leo Bersani, Baudelaire and Freud (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1977), 8-15.

[6] Charles Baudelaire, “Journaux intimes,” in Oeuvres complètes. Vol 1, ed. Claude Pichois (Paris: Gallimard, 1975), 647–709. “Qu est ce l’art? Prostitution?”

[7] For more information on Alexander Cabanel, see Michel Hilaire and Sylvain Amic, Alexandre Cabanel, 1823-1889: la tradition du beau (Paris: Somogy Editions d’Art, Musée Fabre, 2010).

[8] Émile Zola, “Nos peintres au Champ-de-Mars,” La Situation (July 1, 1867). “Bercé dans des langes classiques.”